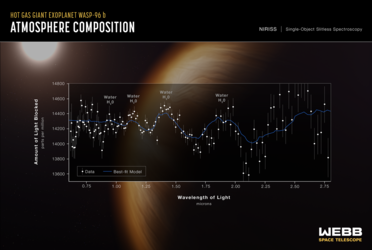

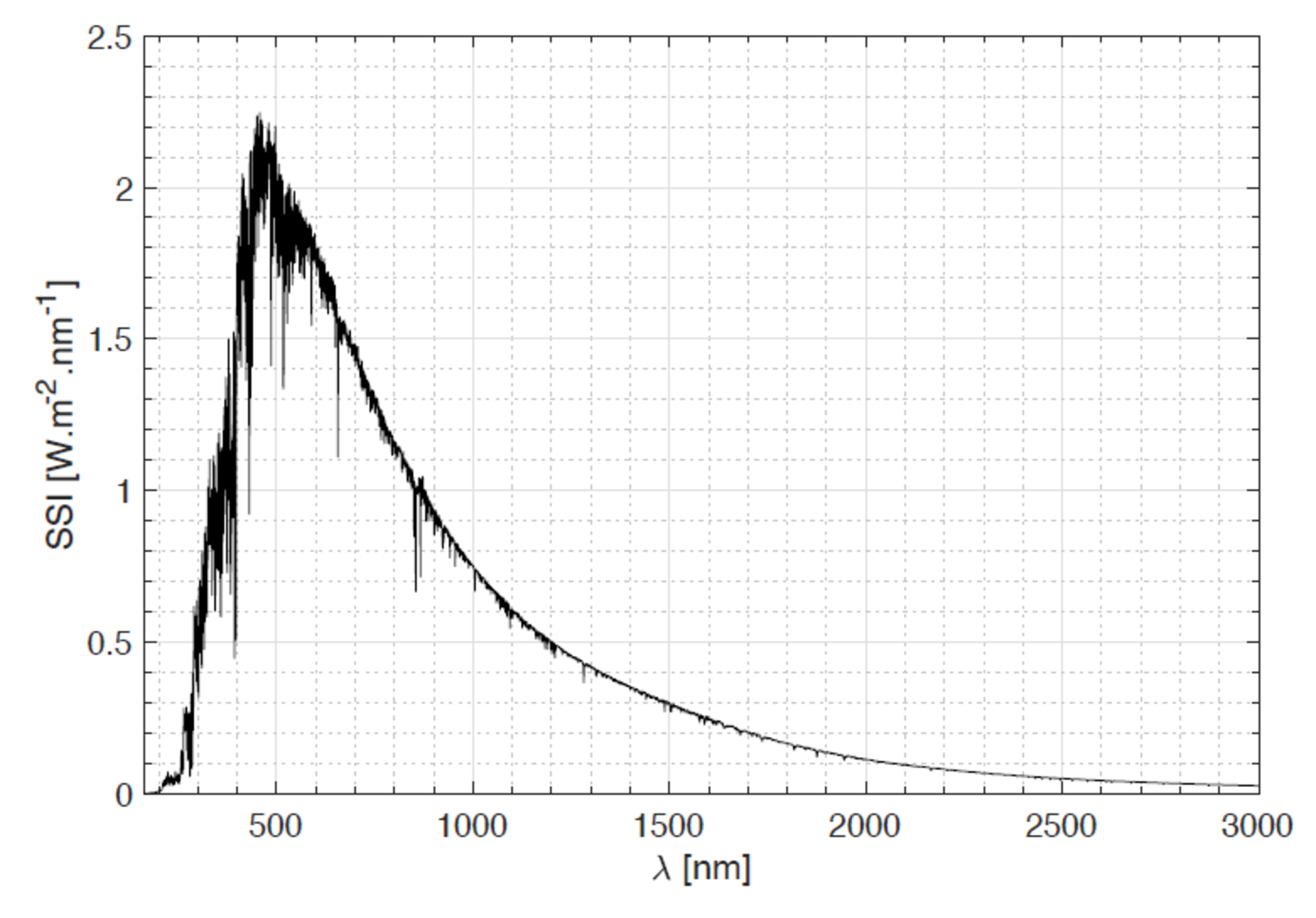

Solar spectrum

The solar reference spectrum in April 2008 as recorded by the Solar instrument on the International Space Station.

Computer models can calculate and predict large-scale events such as our planet’s weather and climate but they need hard numbers to work on. Processing power can simulate our planet, but the researchers need the numbers to key into the computer models and, with so many numbers flowing, inaccuracies quickly add up.

This is where the Solspec instrument comes in. Part of the Solar package on the International Space Station, it was launched with the European Columbus space laboratory in 2008 and tracked the Sun until it was shut down this year. It measured the energy of each wavelength in absolute terms and its variability – a feat that requires a higher order of precision than relative measurements. As an analogy, it is easy to feel a change in temperature, but nobody on Earth can sense the exact temperature without a thermometer.

The teams behind the facility, the Belgian BIRA-IASB institute and France’s Latmos, improved the accuracy of the reference data across the Sun’s spectrum down to 1.26% and, more importantly, an estimation of how accurate this variation is – meaning the team not only knows how much energy per square metre is emitted per wavelength, but also the margin of error. This number might seem insignificant, but the more accurate it is, the better researchers can understand how our climate has changed and is changing.