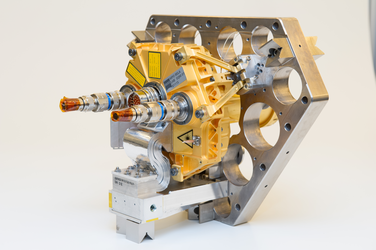

Card-thick space antenna

A whole new kind of large space antenna has been tested in realistic space conditions. This 5 m-diameter reflector seen being lowered into ESA’s Large Space Simulator appears translucent because it is a few tenths of a mm thick – thinner than a piece of card.

“This marked the first full-scale environmental testing of our new LABUM – Large Apertures Based on Ultrastable Shell-Membrane – technology innovated and developed at the Institute of Lightweight Structures at the Technical University of Munich (TUM),” explains Leri Datashvili, running the project for TUM.

LABUM is an attempt to fill a hole in current European space capabilities. Large-scale antenna reflectors are increasingly required for telecommunications, science and Earth observation missions. Up until now, European industry has not been able to field reflectors larger than 4 m in diameter, while the US, Japan and Russia are operating much larger reflectors in orbit.

“This reflector has been made from carbon fibre reinforced silicone, which has the twin advantages of flexibility and ‘thermo-elastic stability’ – meaning it is able to hold its shape across a broad range of temperatures.” explains Julian Santiago Prowald of ESA’s Structures Section.

LABUM’s material is able to maintain its shape without the kind of pretensioning required by the wire mesh alternative, accordingly enabling a much lighter backing structure. The design is also scalable and modular – this prototype could in principle be reproduced at much larger size, up to 18 m or more.

Part of ESA’s ESTEC Test Centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, the LSS is Europe’s largest thermal vacuum chamber, reproducing space-quality vacuum within liquid nitrogen-chilled walls. An array of IMAX-class light bulbs simulates the unfiltered sunlight encountered in orbit.

The three-day test last month gathered precise data on how LABUM’s shape responds to changing temperatures. The simulation reproduced a worst-case scenario where bright sunlight heats up the reflector’s centre while its edges remained colder than –100 C.

Photogrammetry cameras were used to trace millimetre-scale distortion across the reflector, while thermocouples and infrared cameras took the temperature all along its surface.

Team behind the test

“The development has been led by ESA’s Structures Section in close collaboration with the Antenna Section,” adds Julian.

“The Test Centre team also contributed advanced temperature and shape measurement techniques inside the Large Space Simulator, making it possible to achieve the high-quality results.”

LABUM is an activity within ESA’s Basic Technology Research Programme – ESA’s basic ‘ideas factory’ for promising new technologies – with TUM as the prime contractor, HPS-GmbH as subcontractor, with the participation of Munich University of Applied Sciences, and Wacker Silicones, AAC.

The activity was conceived by ESA’s Directorate of Technical and Quality Management as part of a European roadmap of new technologies in the domain of very large space apertures.

“The strong support of the TRP programme was essential,” concludes Julian. “The programme oversaw the complex set-up of technology development efforts and the use of highly overbooked test facilities like ESTEC’s Large Space Simulator.”

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland