Five years of unique science on Columbus

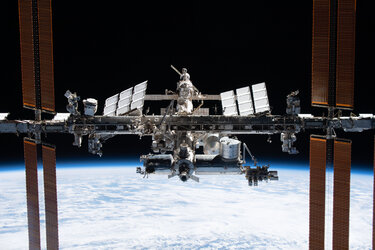

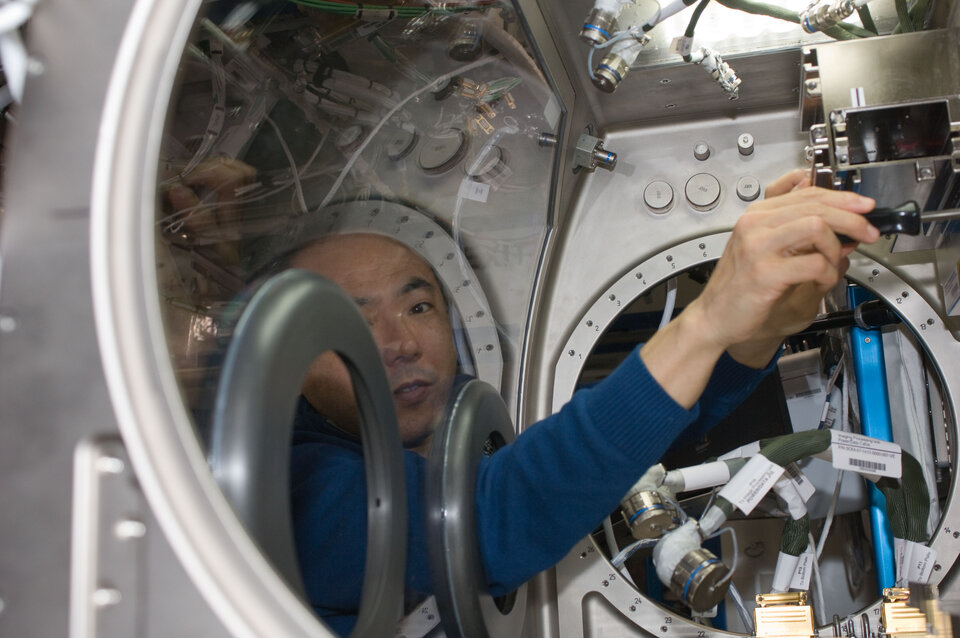

Since Europe’s Columbus laboratory module was attached to the International Space Station five years ago, it has offered researchers worldwide the opportunity to conduct science beyond the effects of gravity.

A total of 110 ESA-led experiments involving some 500 scientists have been conducted since 2008, spanning fluid physics, material sciences, radiation physics, the Sun, the human body, biology and astrobiology.

The Space Station allows researchers to play with a force that is fixed on Earth: gravity. ‘Turning off’ gravity and performing experiments in space over long periods can reveal the inner workings of natural phenomena.

“We focus research on achieving scientific discoveries, developing applications and benefitting people on Earth while preparing for future space exploration,” explains Martin Zell, responsible for ESA’s utilisation of the European orbital laboratory.

Studying colloids – tiny particles in liquids – is one area of research hampered by gravity. Colloids are found in many liquids such as milk, paint and even in our bodies, yet they are so small you need an electron microscope to study them. At this scale, gravity will always influence the results, but in space experiments can be run repeatedly without interference.

The Colloid experiment on Columbus has shown how ‘quantum forces’ can be used to control colloid structures. It confirmed the effect of these forces as predicted theoretically over 30 years ago, but observed for the first time in 2008. The findings are part of the building blocks for creating nanomaterials.

Research inside Columbus is also helping scientists to understand the human body. Astronauts in space absorb more salt without absorbing more fluids – contradicting generally accepted medical knowledge.

It turns out that high-salt diets seem to be causing bone loss in astronauts. Until now, bone loss was thought to be caused by the physical effect of living in weightlessness. This new result has implications for people suffering from osteoporosis on Earth.

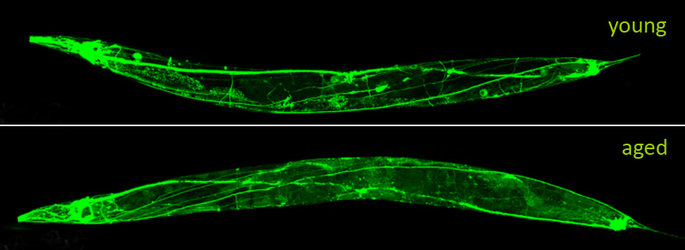

Delving deeper, cell research is offering clues on how to control ageing. The Roald biology experiment revealed that certain enzymes in our immune systems are more active in space, showing scientists on the ground where to look to combat premature cell death.

There are also experiments mounted outside of the Columbus module. The first of a series of Expose experiments has shown that living organisms can survive space travel.

A number of bacteria, seeds, lichen and algae spent 18 months outside Columbus in space with no protection from the harsh space environment. When they were returned to Earth in 2009, the lichen awoke from their dormant state, highlighting the possibility that life forms could possibly hitch a ride on asteroids to planets.

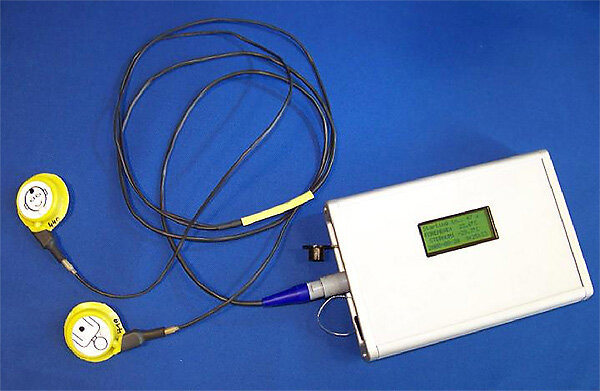

Closer to home, technology developed for Columbus research is also being used by hospitals and firefighters. A new type of thermometer designed for astronauts reads temperatures continuously via two sensors on the forehead and chest. The technology was patented as a spin-off and is of great use for heart surgery and monitoring newborn babies.

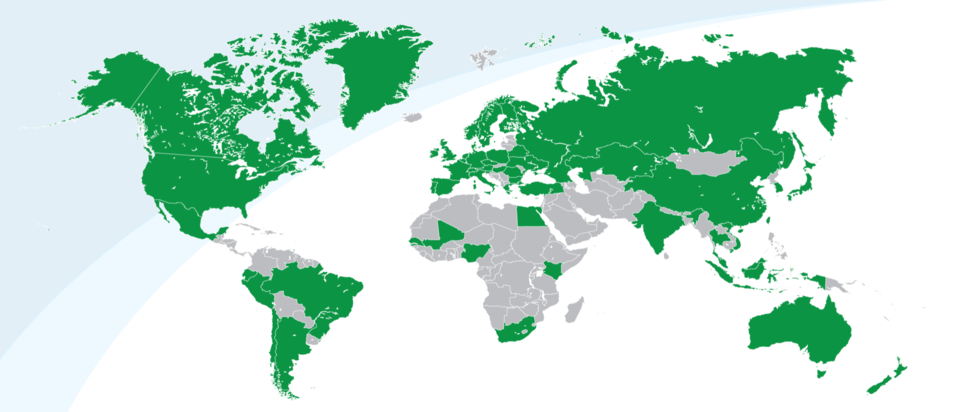

“Our European laboratory in space is accessible around the clock and allows us to do outstanding research with the international science community,” says Martin. “We already have a high demand and continuously receive requests for research in Columbus, so we can expect plenty of exciting results.”

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland