Bricks from Moon dust

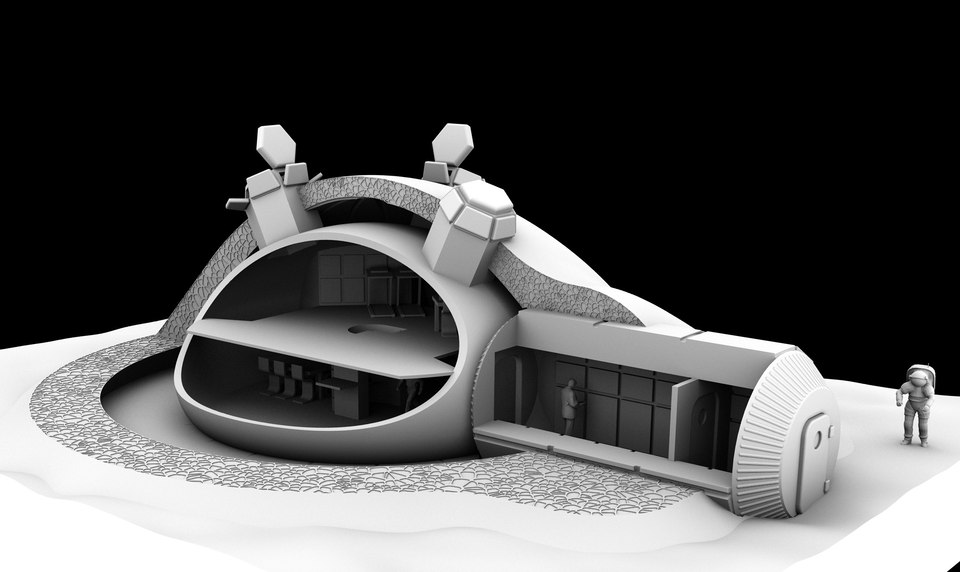

Lunar masonry starts on Earth. European researchers are working with Moon dust simulants that could one day allow astronauts to build habitats on our natural satellite and pave the way for human space exploration.

The surface of the Moon is covered in grey, fine, rough dust. This powdery soil is everywhere – an indigenous source that could become the ideal material for brickwork. You can crush it, burn it and compress it.

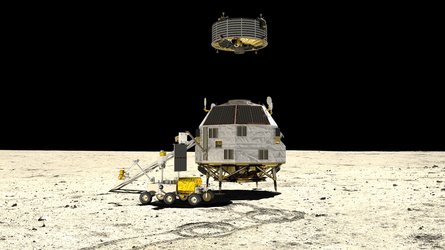

“Moon bricks will be made of dust,” says Aidan Cowley, ESA’s science advisor with a wealth of experience in dealing with lunar soil. “You can create solid blocks out of it to build roads and launch pads, or habitats that protect your astronauts from the harsh lunar environment.”

European teams see Moon dust as the starting point to building up a permanent lunar outpost and breaking explorers’ reliance on Earth supplies.

Access the video

Lunar dust ‘made in Europe’

Lunar soil is a basaltic material made up of silicates, a common feature in planetary bodies with volcanism.

“The Moon and Earth share a common geological history, and it is not difficult to find material similar to that found on the Moon in the remnants of lava flows,” explains Aidan.

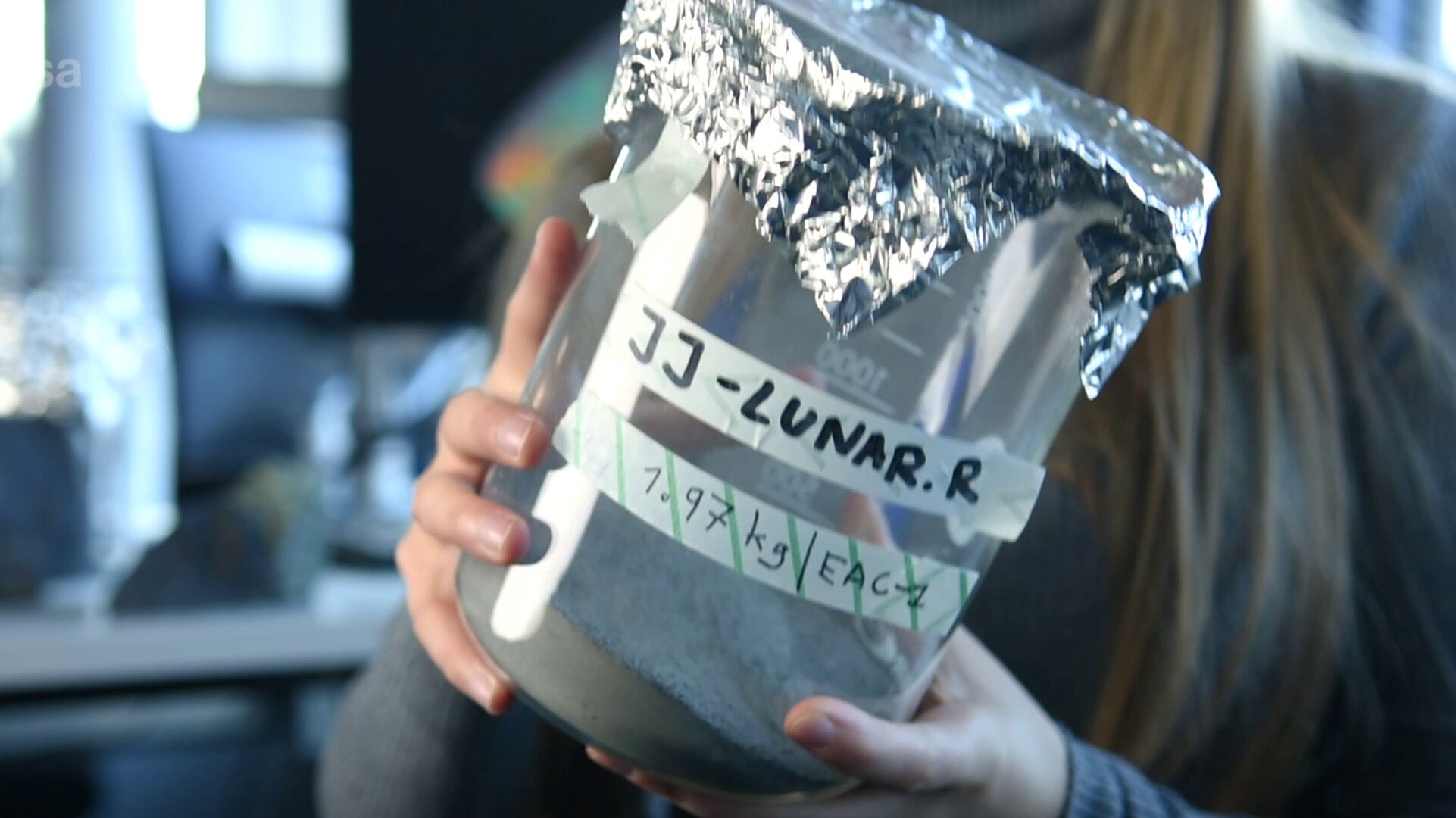

Around 45 million years ago, eruptions took place in a region around Cologne, in Germany. Researches from the nearby European Astronaut Centre (EAC) found that the volcanic powder in the area is a good match with what lunar dust is made of. And there is plenty of it.

The lunar dust substitute ‘made in Europe’ already has a name: EAC-1.

The Spaceship EAC initiative is working with EAC-1 to prepare technologies and concepts for future lunar exploration.

“One of the great things about the lunar soil is that 40% of it is made up of oxygen,” adds Aidan. One Spaceship EAC project studies how to crack the oxygen in it and use it to help astronauts extend their stay on the Moon.

Moon’s magnetic call

Bombarded with constant radiation, lunar dust is electrically charged. This can cause particles to lift off the surface. Erin Tranfield, a member of ESA’s lunar dust topical team, insists that we still need to fully understand its electrostatic nature.

Scientists do not yet know its chemical charge, nor the consequences for building purposes. Trying to recreate the behaviour of lunar dust in a radiation environment, Erin ground the surface of lunar simulants. She managed to activate the particles, but erased the properties of the surface.

“This gives us one more reason to go back to the Moon. We need pristine samples from the surface exposed to the radiation environment,” says Erin. For this biologist who dreams of being the first woman on the Moon, a few sealed grams of lunar dust would be enough.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland