Medical research

As we breathe in and out we release some nitric oxide molecules in our breath. We know that the amount of nitric oxide exhaled can be an indication of inflammation in the lungs. Doctors on Earth are measuring the amount of nitric oxide to help diagnose asthma and other diseases of the lungs, but the method is not yet fully understood.

For future exploration of our Universe space physicians are always looking for easier ways to monitor astronaut health. There are concerns that dust that could be dangerous to human health on other planets or our Moon, for example. Apollo lunar astronauts said that the Moondust was all-invasive, clinging to equipment, clothes and getting into their spacecraft.

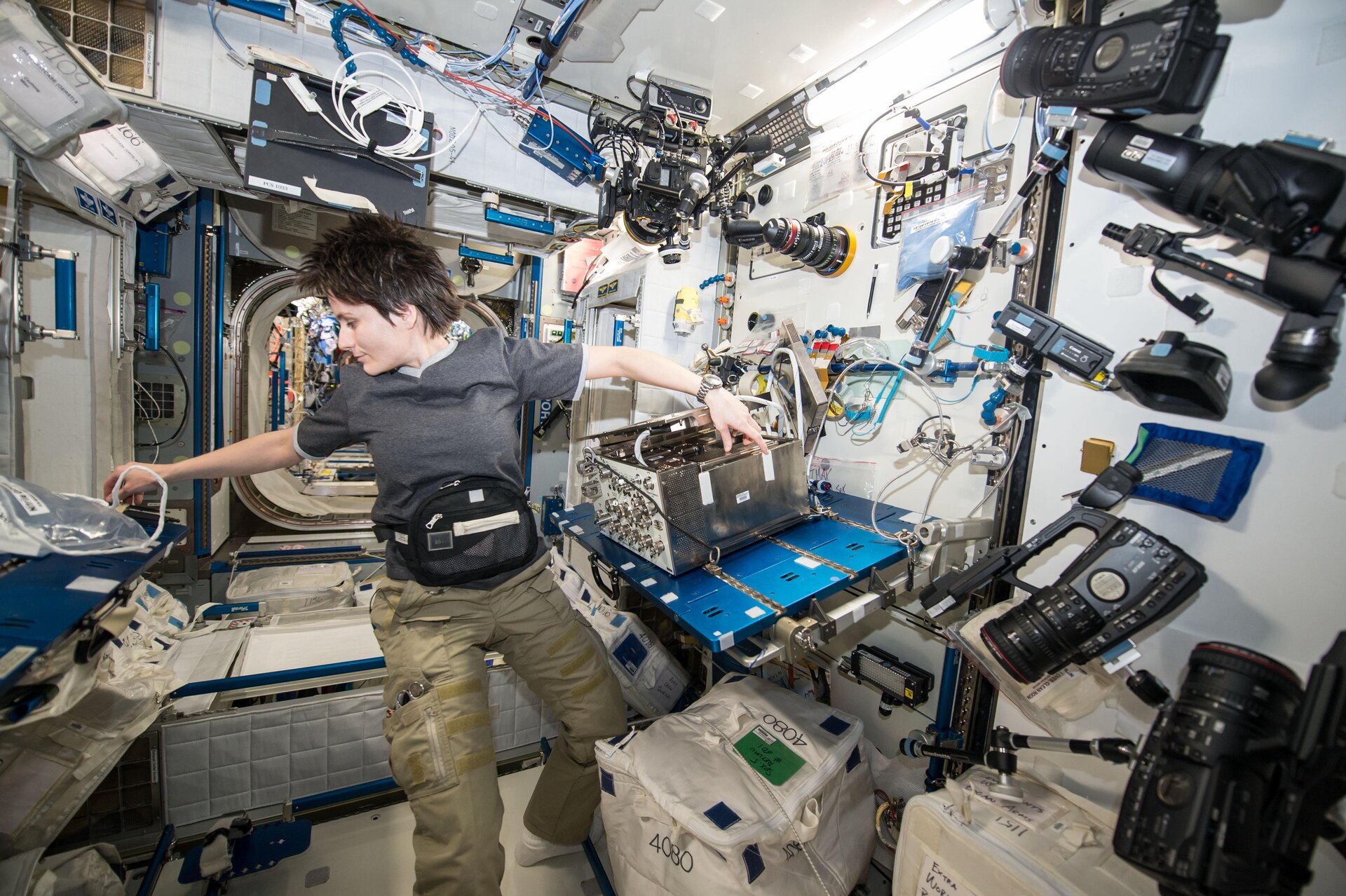

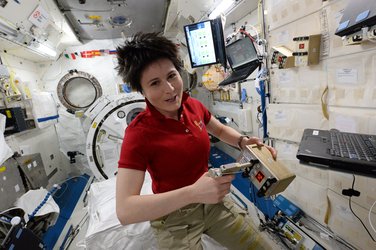

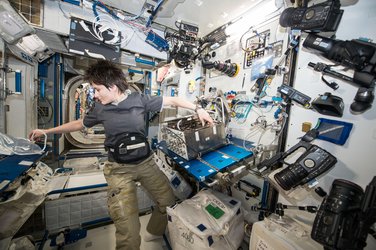

To test nitric oxide monitoring in space and assess its value as a diagnostic tool, ESA astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti and other astronauts will wear a portable gasmask that analyses the molecule as they breathe. The experiment was performed at normal Space Station pressure but also at a half-pressure in the Quest airlock to simulate the atmosphere on a lunar base. This was the first time that Quest was used for scientific research, its main purpose until then being for spacewalks.

Previous ESA experiments have led to improved hospital equipment and diagnosis. The Airway monitoring experiment will add to knowledge of using nitric oxide in our breath as a diagnostic tool. The experiment also paves the way for sending astronauts to the Moon and beyond, where they would have to live healthily self-sufficiently.

Where bones meet they are protected by cartilage that reduces friction and absorbs shock. Our bodies do not repair damaged cartilage well, leading to painful joints and some forms of arthritis.

Researchers know that to keep cartilage healthy it must be used regularly under load. Overexertion, however, can damage the tissue as well and the ideal level of exercise is unclear.

This experiment investigates the effects on cartilage of living in space. As astronauts in microgravity have little to no pressure on their joints, it is expected that Samantha will lose some of her cartilage. To test the theory, this experiment is scanning astronaut’s knees by MRI before and after their mission to chart changes in their cartilage.

This research will assess risk for people travelling in space and bedridden patients on Earth, as well as help to develop methods of preventing cartilage damage and increasing our understanding of arthritis.

Our bodies know roughly what time of day it is, making us feel sleepy at night. Our biological clock follows Earth’s 24‐hour cycle but reacts to sunlight. In our modern world many people live outside of the natural cycle, staying up late or working night shifts. As a result, problems with sleeping are common but not fully understood.

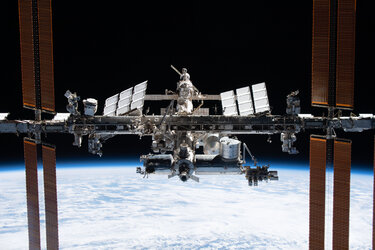

Samantha experienced 16 sunrises and sunsets every day on the International Space Station as it circles Earth, making it a unique place to study circadian rhythms. No other place near Earth offers 90-minute days that put a serious strain on people’s body clocks.

How her biological clock reacts is of interest to the next generation of astronauts as well as people on Earth who work irregular hours, such as doctors and emergency workers. The data will be shared and compared with isolation studies such as ESA’s Mars500 and in places that experience the opposite to short days, as in Antarctica where people on the research base Concordia live four months without sunlight.

The Circadian rhythms experiment measures astronaut temperature and melatonin, a hormone linked to sleep. Samantha’s readings were measured continuously using Thermolab, a new sensor that monitors temperature without impractical thermometers.

The findings will help in finding out how to rest effectively and be alert when most needed, a skill that many would benefit from, especially astronauts who need to be ready for spacecraft dockings at irregular intervals.

Scientists want to know how to feed people on future missions such as to Mars. Planning an 18-month mission to the Red Planet requires accommodating all hardware and supplies down to the kilogram. This experiment sets out to ask: how much food does an astronaut need for 18 months in space? Imagine an astronaut running out of energy during a critical moment such as a Mars landing.

Access the video

This experiment looks at the energy expenditure of astronauts to plan adequate but not excessive food supplies. It is a complex experiment and many astronauts are involved. ESA astronauts André Kuipers, Luca Parmitano, Alexander Gerst and others took part in this experiment on their missions before Samantha.

As with most physiology experiments, measurements are conducted before, during and after flight. This is the only way to record the differences between living on Earth and in microgravity.

The space part of this experiment lasts 11 days. Space food is eaten from a special package on the first two days and everything is registered with bar codes and on written forms to know exactly what Samantha will eat. She will drink water with deuterium isotopes and regularly collect water and urine samples. The isotopes allow the scientists to examine how Samantha’s energy levels changed over the 11-day period.

A mask measured the amount of oxygen Samantha absorbs for 20–50 minutes at a time during the second day to deduce energy consumption. All movements are recorded during the experiment using an activity monitor.

Our skin protects us, regulates our temperature and helps us to feel objects. As we grow older, our skin becomes more fragile and takes longer to heal from injuries. Astronauts lose more skin cells and age faster during spaceflight. A common complaint of astronauts is cracking skin and rashes or itchiness.

This experiment is the first research into skin in space, collecting data on skin structure, oxygenation, hydration and elasticity. The goal is to develop a computer model of how skin ages. Results on Samantha’s skin will improve the model and could contribute to helping protect people’s skin on Earth as well as in space.

Space headaches

Almost three-quarters of astronauts suffer from headaches in space, which usually are worse in the first few weeks. Described by some as ‘exploding’, the headaches are unlike any felt on Earth. This could be bad news for space tourists who spend a short time in space and want to enjoy it as much as possible.

This experiment uses regular questionnaires to investigate the headaches experienced by astronauts. Samantha filled in a questionnaire regularly to study the number of headaches she has on the Station. The researchers are looking to understand the causes of headaches in space. Are they linked to the fluid movement towards the head in microgravity? Is there a link between headaches on the ground and in space?

ESA astronaut André Kuipers was the first test subject during his mission in 2012, followed by ESA astronauts Luca Parmitano and Alexander Gerst. The headaches are classified and analysed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders.

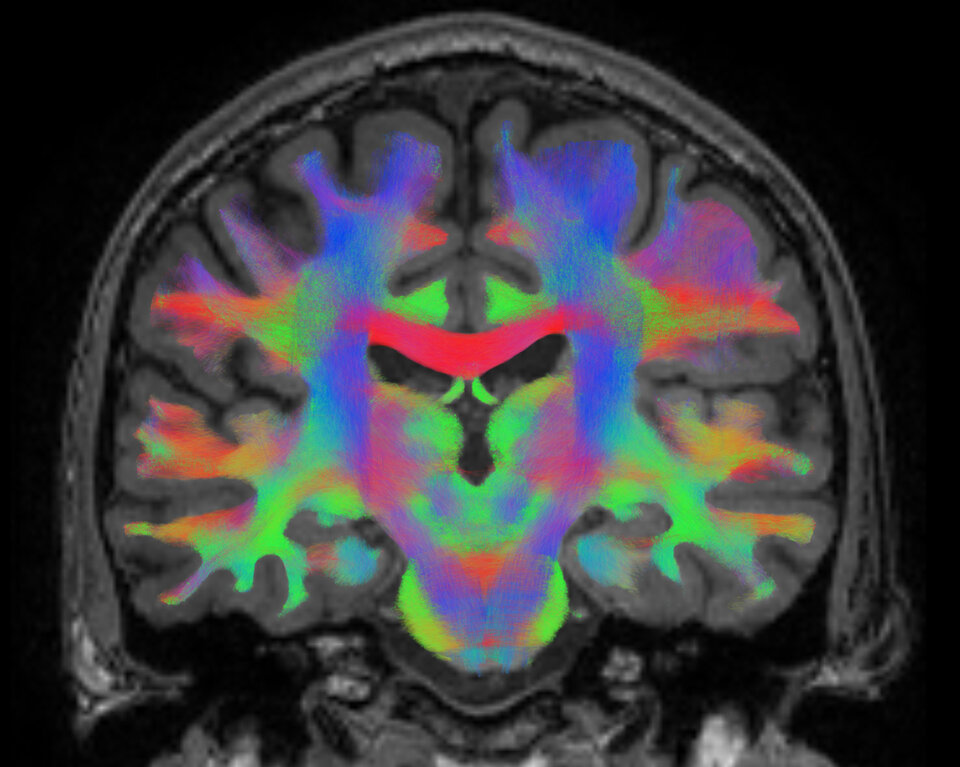

BRAIN-DTI

Humans are adaptable beings. Wear glasses that turn your view of the world upside-down and within two weeks your brain will have adapted to the upside-down world.

Researchers suspect that astronauts’ brains adapt to living in weightlessness by using previously untapped links between neurons. As the astronauts learn to float around in their spacecraft, left–right and up–down become second nature as these neuronal connections are activated.

To confirm this theory, up to 16 astronauts will be put through advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanners before and after their flights to study any changes in their brain structure. A control group on ground will undergo the same scans for further comparison.

DEXTROUS-GRIP

In more than 20 experiments flown over the last 15 years on parabolic flights that offer 20 seconds of weightlessness, a team of scientists has charted how humans cope with grasping objects in space. Astronauts often perform delicate manoeuvres on small objects, and calculating how living in weightlessness influences their grasp and fine motor controls is important in an environment that allows little room for error.

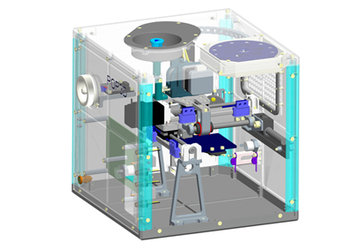

The work carried out on parabolic flights has paved the way for an experiment that Samantha ran on the Space Station during the Futura mission. She gripped a purpose-built sensor with her eyes open and then closed to assess how the body adapts to situations where there is no up or down.

These experiments are also helpful to engineers designing prosthetic limbs on Earth.

EDOS-2

The Early Detection of Osteoporosis in Space experiment will look at changes in Samantha’s bone structure before and after her flight by studying markers in her blood and urine, as well as through a tomography scan. For this experiment, she followed a strict diet during the data collection stage.

All astronauts lose up to 1% of their bone mass each month in space, similar to osteoporosis. Obviously this is worrying for longer missions to far-away planets or celestial bodies. Researchers are interested to find out if they can detect the changes quickly and also when the changes occur. This research will help detect osteoporosis on Earth, a disease that most people over 55 suffer from to some degree.

Immuno-2

Living in space is a wonderful experience but it can take its toll on an astronaut’s body: half of astronauts return sick after a mission to the International Space Station.

Stress is a response of the body as it adapts to hostile environments. This broad definition includes stress from speaking in front of an audience, stress from a wound or stress from living in weightlessness in a fragile spacecraft far from home.

The Immuno-2 experiment takes a holistic approach to consider how stress affects our immune system. Using brain scans, monitoring breathing and looking at samples from Samantha’s hair, the researchers hope to understand how living in stressful conditions affects her immune system.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland