Closing the recycling circle

The International Space Station welcomes up to eight supply vessels a year bringing oxygen, water and food for the six astronauts continuously circling our planet. Building, launching, docking and unloading these spacecraft is costly and time-consuming – is there a better way?

Many mission designers dream of crewed spacecraft that require no resupplies. A vehicle that indefinitely recycles astronaut waste such as exhaled carbon dioxide and urine and turns it into fresh oxygen and water like a miniature Earth would be ideal.

Even a half-closed ecosystem would save a great deal of planning and weight, freeing up space for more experiments and travel.

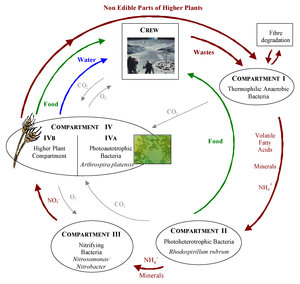

ESA’s Melissa project has been working on this goal for over 25 years by looking at how to fit bacteria, algae, plants, chemicals and physical processes together into a self-sustaining circuit that turns astronaut waste into fresh supplies.

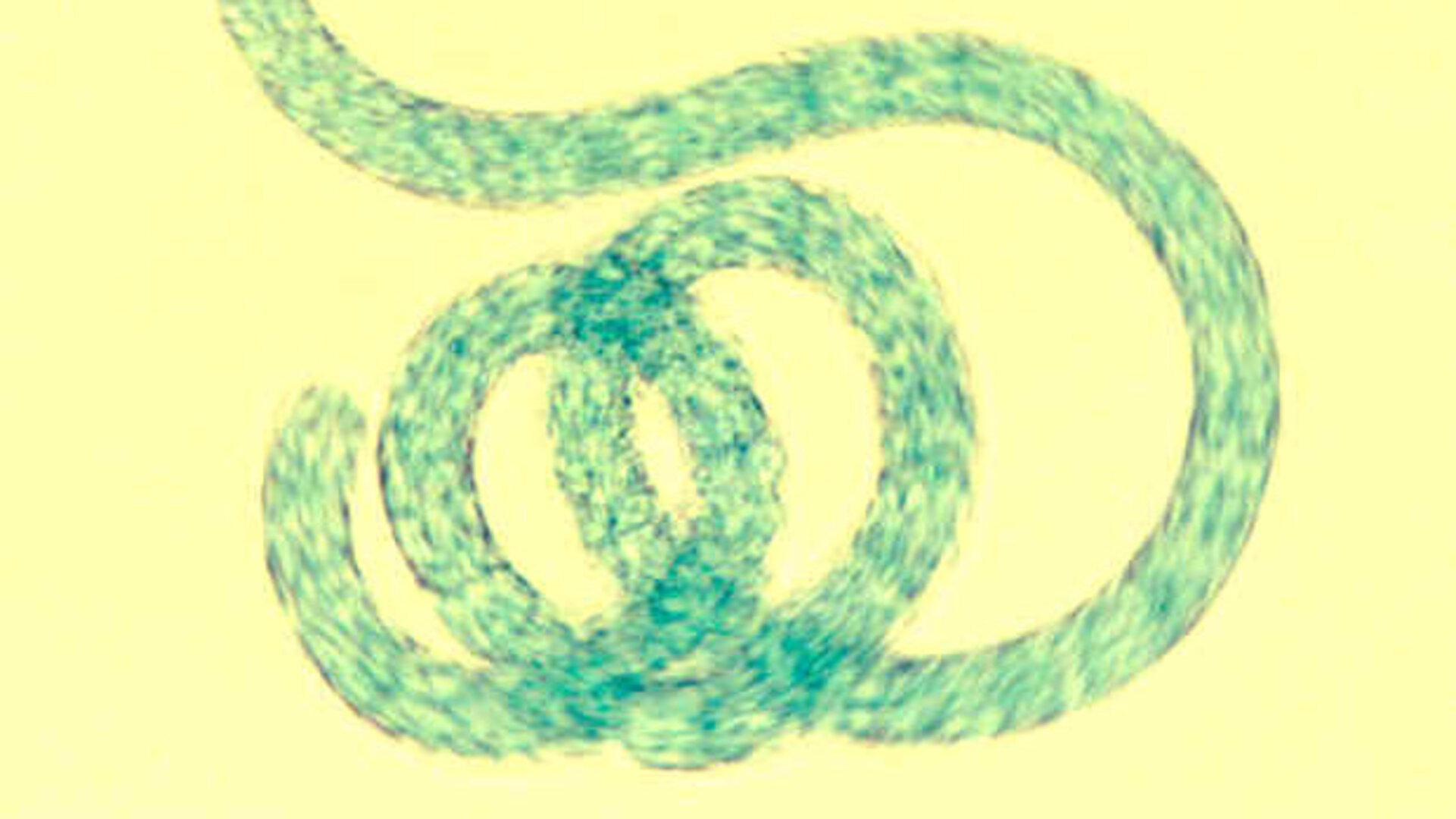

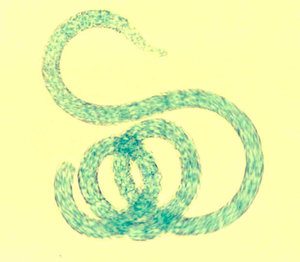

Spirulina bioreactors

The ‘Melissa loop’ is about to take off. All around the world – and soon above it – key pieces of the puzzle are being tested to see how they fit into the whole.

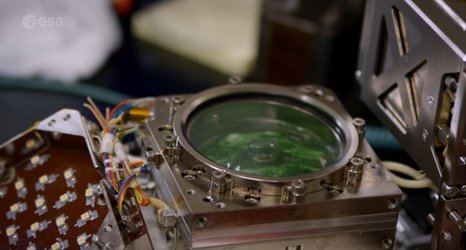

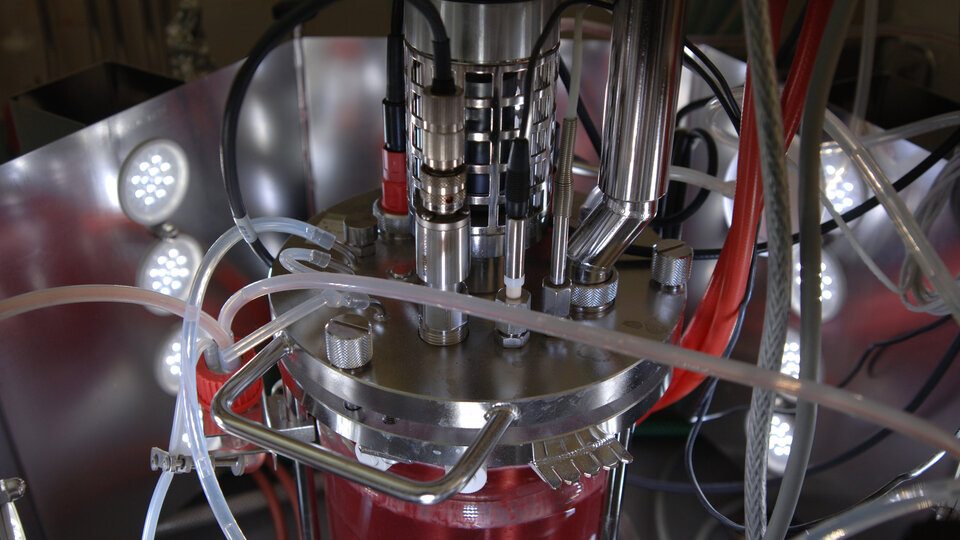

First up is a photo-bioreactor that uses light to power organisms for turning unwanted carbon dioxide into something we can use.

Bioreactors cultivate organisms in closed containers but getting a species to thrive is no easy task. As the occupants grow they need space and different lighting. And continuously drawing the good stuff out of the reactor ready for human consumption cannot be allowed to disturb the mini-ecosystem.

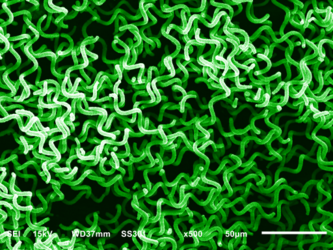

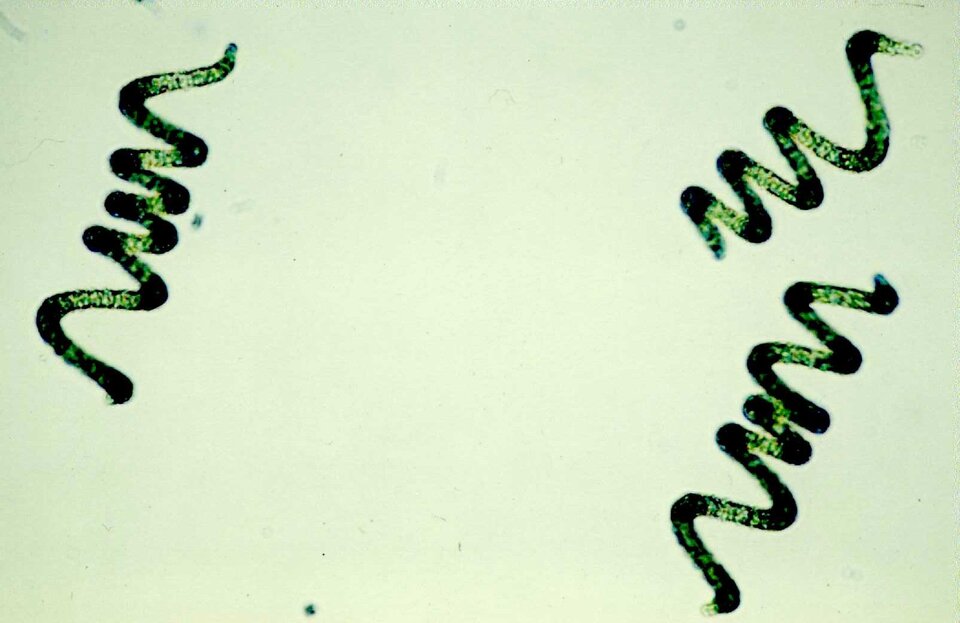

The Melissa team has made great progress in this domain and is ready to test their system in space. In the next 12 months they will send Spirulina algae to the International Space Station to see how well it grows in microgravity.

Spirulina has been harvested for food in South America and Africa for centuries. It turns carbon dioxide into oxygen, multiplies rapidly and can also be eaten as a delicious protein-rich astronaut meal.

The first experiment will simply assess how Spirulina adapts to weightlessness so researchers can fine-tune the unit.

The next step is a hands-on test: an experiment that mimics astronauts’ breathing will be connected to the bioreactor so the Spirulina can grow on a steady stream of carbon dioxide, delivering oxygen in return.

If these early tests in space go well, the team will be a long way towards the ultimate goal of recycling carbon dioxide, water and organic waste into food, water and oxygen.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland