Stressed seedlings in space

Life on Earth has a myriad of problems, but gravity isn’t one of them – staying grounded means organisms can soak up the light and heat that enables growth.

It’s no wonder that the free-floating environment of space stresses organisms, which survive only if they can adapt. Like humans, plants have proven their robustness in space. Now, thanks to the International Space Station, we know more on how they cope with weightlessness.

Adventures of space farming

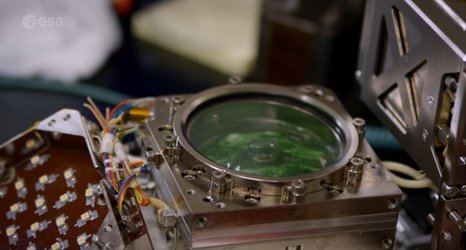

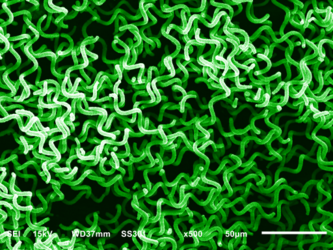

To understand how light and gravity affect plant growth, researchers from the US and Europe have grown more than 1700 thale cress seedlings in Europe’s Columbus module.

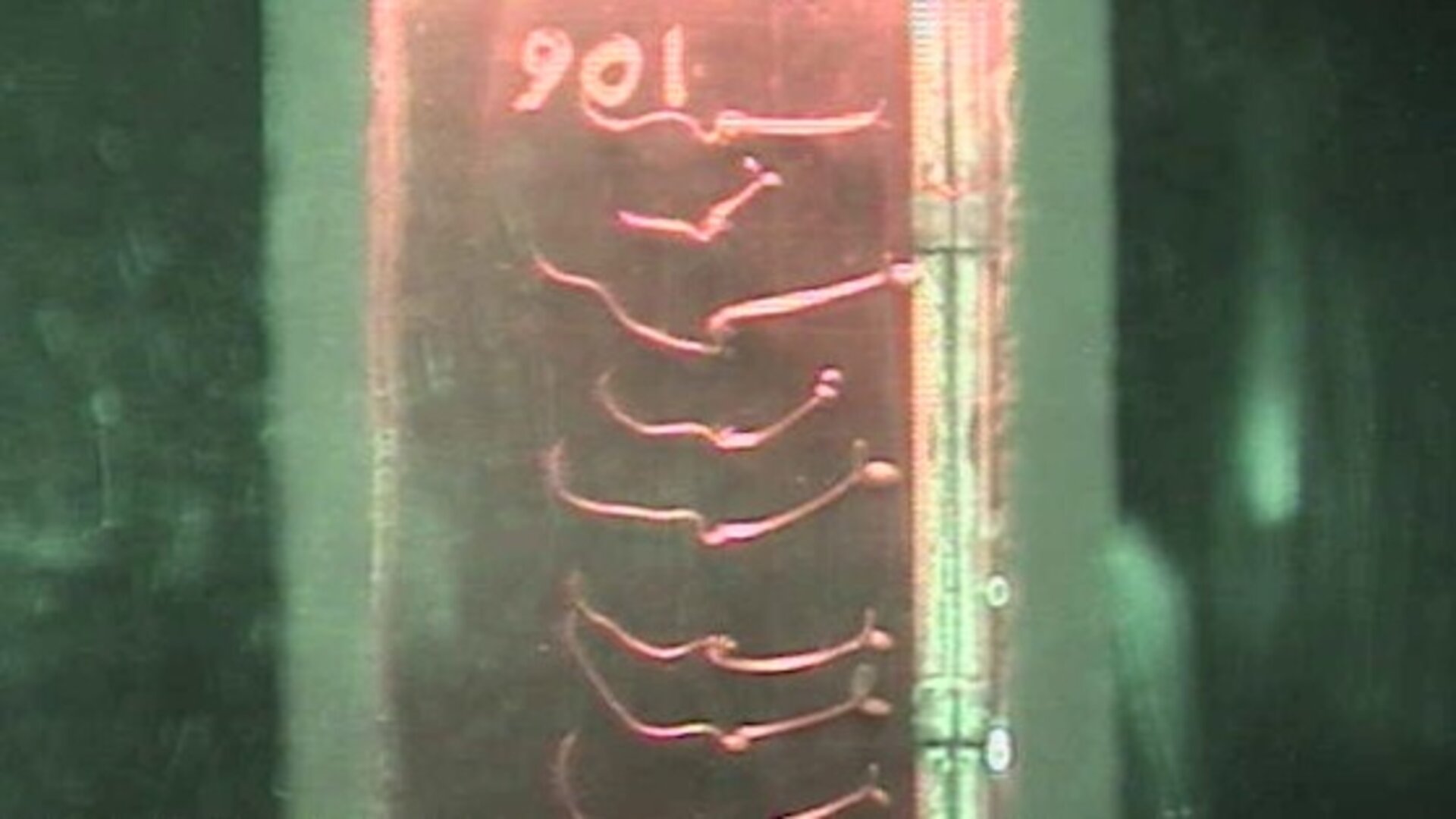

Germinated in prepacked cassettes monitored by ground control, the seedlings were harvested after six days, frozen or preserved and returned to Earth for inspection.

Researchers are now working with realtime images of the seeds as they grew and genetic and molecular analyses of the returned seedlings.

Access the video

What were they hoping to find?

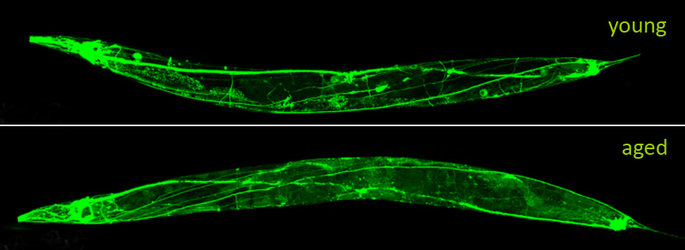

On Earth, roots grow down into the soil, reaching for water and minerals. Weightless disrupts this natural route, altering cell growth unless the plant can overcome it.

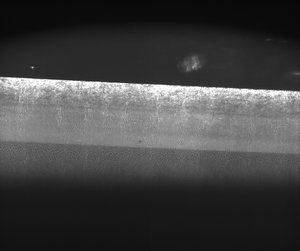

The results so far are pointing to some interesting conclusions. Obviously, seedlings in microgravity grew random roots but they still managed to grow. Plant genes known to overcome environmental stresses on Earth – heat, frost, salinity – kick into gear. Red light seems to help reregulate cell growth interrupted by weightlessness.

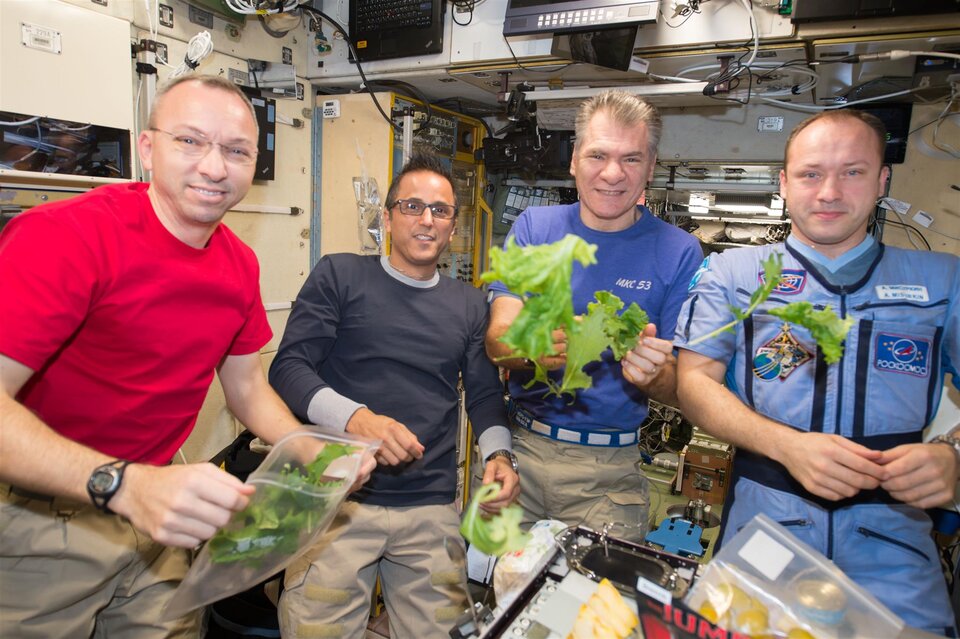

The most recent lettuce harvest on the Space Station shows plants can already mature in space. So why study the seedlings?

In this case, knowledge of how plants overcome gravitational stress to mature into harvestable crops is growing power.

The new results suggest gravity may not be the biggest obstacle to growing plants in space, which is good news for future Moon and Mars colonies. We won’t make it far into space if we can’t grow our own food along the way.

Back on Earth, global climate change is affecting agriculture, and understanding how plants respond to stress and adapt at genetic and molecular levels means we can help to increase agricultural efficiency in general.

It may be a while before space farm to space table becomes the next big thing, but the latest experiments have taken us one step closer.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland