Antarctica loses grip

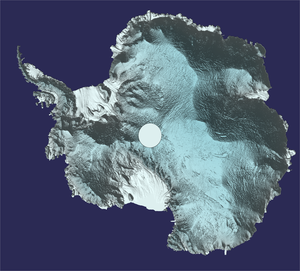

ESA’s CryoSat mission has revealed that, over the last seven years, Antarctica has lost an area of underwater ice the size of Greater London. This is because warm ocean water beneath the continent’s floating margins is eating away at the ice attached to the seabed.

Most Antarctic glaciers flow straight into the ocean in deep submarine troughs. The place where their base leaves the seabed and begins to float is known as the grounding line.

These grounding lines typically lie a kilometre or more below sea level and are inaccessible even to submersibles, so remote methods for detecting them are extremely valuable.

A paper published today in Nature Geoscience describes how CryoSat was used to map grounding-line motion along 16 000 km of Antarctic coastline.

Research led by Hannes Konrad from the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling at the UK’s University of Leeds shows that between 2010 and 2017 the Southern Ocean melted 1463 sq km of underwater ice.

The team tracked the movement of Antarctica’s grounding line thanks to CryoSat and has produced the first complete map showing how this submarine edge is losing its grip on the seafloor.

The biggest changes are seen in West Antarctica, where more than a fifth of the ice sheet has retreated across the seafloor faster than the pace of deglaciation since the last ice age.

Dr Konrad said, “Our study provides clear evidence that retreat is happening across the ice sheet due to ocean melting at its base, and not just at the few spots that have been mapped before now.

“This retreat has had a huge impact on inland glaciers, because releasing them from the seabed removes friction, causing them to speed up and contribute to global sea-level rise.”

Although CryoSat is designed to measure changes in the ice-sheet elevation, these can be translated into horizontal motion at the grounding line using the Archimedes principle and knowledge of the glacier and seafloor geometry.

The researchers also found some unexpected behaviour.

Although retreat of the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica has sped up, at the neighbouring Pine Island Glacier – until recently one of the fastest retreating on the continent – it has halted. This suggests that the ocean melting at its base has paused.

Dr Konrad added, “These differences emphasise the complex nature of ice-sheet instability across the continent, and being able to detect them helps us to pinpoint areas that deserve further investigation.”

Co-author Andy Shepherd said, “We were delighted at how well CryoSat is able to detect the motion of Antarctica’s grounding lines.

“They are impossible places to access from below so it’s a fantastic illustration of the value of satellite measurements for identifying and understanding environmental change.”

ESA CryoSat mission manager Tommaso Parrinello added, “Even though CryoSat is now approaching its eighth year in orbit – more than twice its intended lifetime – it’s wonderful to see that the mission is still making measurements of the highest quality and enabling new discoveries in polar science.”

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland