Is the ozone layer on the road to recovery?

Satellites show that the recent ozone hole over Antarctica was the smallest seen in the past decade. Long-term observations also reveal that Earth’s ozone has been strengthening following international agreements to protect this vital layer of the atmosphere.

According to the ozone sensor on Europe’s MetOp weather satellite, the hole over Antarctica in 2012 was the smallest in the last 10 years.

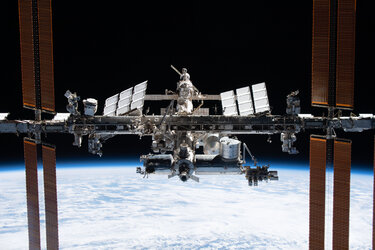

The instrument continues the long-term monitoring of atmospheric ozone started by its predecessors on the ERS-2 and Envisat satellites.

Since the beginning of the 1980s, an ozone hole has developed over Antarctica during the southern spring – September to November – resulting in a decrease in ozone concentration of up to 70%.

Ozone depletion is more extreme in Antarctica than at the North Pole because high wind speeds cause a fast-rotating vortex of cold air, leading to extremely low temperatures. Under these conditions, human-made chlorofluorocarbons – CFCs – have a stronger effect on the ozone, depleting it and creating the infamous hole.

Over the Arctic, the effect is far less pronounced because the northern hemisphere’s irregular landmasses and mountains normally prevent the build-up of strong circumpolar winds.

Reduced ozone over the southern hemisphere means that people living there are more exposed to cancer-causing ultraviolet radiation.

International agreements on protecting the ozone layer – particularly the Montreal Protocol – have stopped the increase of CFC concentrations, and a drastic fall has been observed since the mid-1990s.

However, the long lifetimes of CFCs in the atmosphere mean it may take until the middle of this century for the stratosphere’s chlorine content to go back to values like those of the 1960s.

The evolution of the ozone layer is affected by the interplay between atmospheric chemistry and dynamics like wind and temperature.

If weather and atmospheric conditions show unusual behaviour, it can result in extreme ozone conditions – such as the record low observed in spring 2011 in the Arctic – or last year’s unusually small Antarctic ozone hole.

To understand these complex processes better, scientists rely on a long time series of data derived from observations and on results from numerical simulations based on complex atmospheric models.

Although ozone has been observed over several decades with multiple instruments, combining the existing observations from many different sensors to produce consistent and homogeneous data suitable for scientific analysis is a difficult task.

Within the ESA Climate Change Initiative, harmonised ozone climate data records are generated to document the variability of ozone changes better at different scales in space and time.

With this information, scientists can better estimate the timing of the ozone layer recovery, and in particular the closure of the ozone hole.

Chemistry climate models show that the ozone layer may be building up, and the hole over Antarctica will close in the next decades.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland