Melting slows Greenland ice flow

It may seem counter intuitive, but satellite data suggest that part of the Greenland ice sheet moves more slowly if the surface of the ice melts faster.

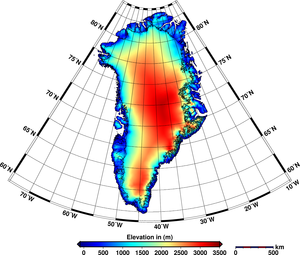

Greenland is losing vast quantities of ice to the ocean, raising sea levels. Icebergs calving from the edge of the ice sheet account for around half of this loss and the other half is because of surface melt.

Once the surface of the ice melts, however, what follows is rather complex.

The Greenland ice sheet is always on the move, flowing under its own weight.

This flow towards the ocean is controlled by several factors, but how surface meltwater drains through the 3 km-thick sheet to the ground below and the effect this has on the speed of ice flow is poorly understood.

To shed more light on what’s going on scientists from the University of Edinburgh in the UK, the Université Savoie Mont-Blanc in France and the University of Sheffield in the UK have studied 30 years of Landsat data.

They investigated if increased surface meltwater increased the flow of ice to the ocean by lubricating the bed at the base of the ice, or if increased meltwater decreased the flow by modifying the bed.

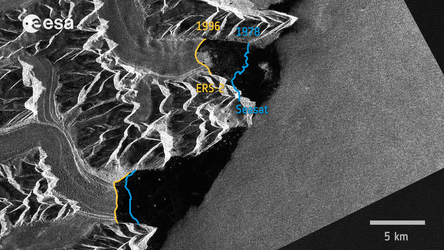

By tracking the movement of stable features such as crevasses in satellite images taken every year from 1985 to 2014, they mapped annual ice speed and compared it with meltwater produced on the surface.

Their findings, published today in Nature, show that surface melt slows the ice flow when it terminates on land.

In summer, snow and ice at the surface melt and the water drains to the bed of the ice sheet, lubricating the base so that the ice slides more quickly. However, the meltwater also establishes efficient drainage systems beneath the ice, draining the meltwater away.

The team found that there was a clear regional slowdown of land-terminating ice in a period when surface meltwater rose by 50%. The reduced lubrication, caused by better meltwater drainage from several years of high-melt summers, appears to be responsible for the slowdown.

Andrew Tedstone from the University of Edinburgh said, “Our investigations suggest that the efficiency of these drainage systems is greater after summers of stronger melting.

“The melting actually reduces the lubrication at the ice sheet base during the following winter – causing winter ice flow to be slower after a warmer summer.

“The results show that since 2002, the flow of an 8000 sq km land-terminating sector of the Greenland ice sheet has slowed down despite an increase in surface melting.”

Noel Gourmelen from the University of Edinburgh added, “It is unclear how much more slowdown we will see under the current and future melting conditions. More research and observations are needed to determine this.”

Their findings suggest that further increases in melting will not cause these land-terminating margins of the ice to speed up. This knowledge will help to predict future contributions that ice sheets make to sea-level change in a warming climate.

It is clear, however, that more research is needed to understand the processes that control the speed of glaciers terminating in the ocean.

Peter Nienow, also from the University of Edinburgh, noted, “While these results may be viewed as a modicum of good news for the Greenland ice sheet, the ongoing acceleration of both glacier surface melt-volumes and ice-motion of ocean-terminating glaciers ensures that its contribution to sea level rise is likely to increase in our warming world.”

Noel Gourmelen added, “We would not have been able to do this research without the free and open access to Landsat data provided by ESA.”

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland