Satellites forewarn of locust plagues

Satellites are helping to predict favourable conditions for desert locusts to swarm, which poses a threat to agricultural production and, subsequently, livelihoods and food security.

Desert locusts are a type of grasshopper found primarily in the Sahara, across the Arabian Peninsula and into India. The insect is usually harmless, but when they swarm they can migrate across long distances and cause widespread crop damage.

During the 2003–05 plague in West Africa, more than eight million people were affected. Up to 100% losses were reported on cereals, 90% on legumes and 85% on pasture. It took nearly $600 million and 13 million litres of pesticide to bring the plague under control.

Swarming occurs when a period of drought is followed by good rains and rapid vegetation growth. These conditions trigger a period of abundant breeding and overcrowding, and the increased contact with other locusts can lead to the formation of large swarms. This behaviour makes locusts more dangerous than grasshoppers.

A 1 sq km swarm contains about 40 million locusts, which eat the same amount of food in one day as about 35 000 people. In other words, a swarm the size of the capital of Mali or the capital of Niger will eat the same amount of food as half the entire population of the respective country.

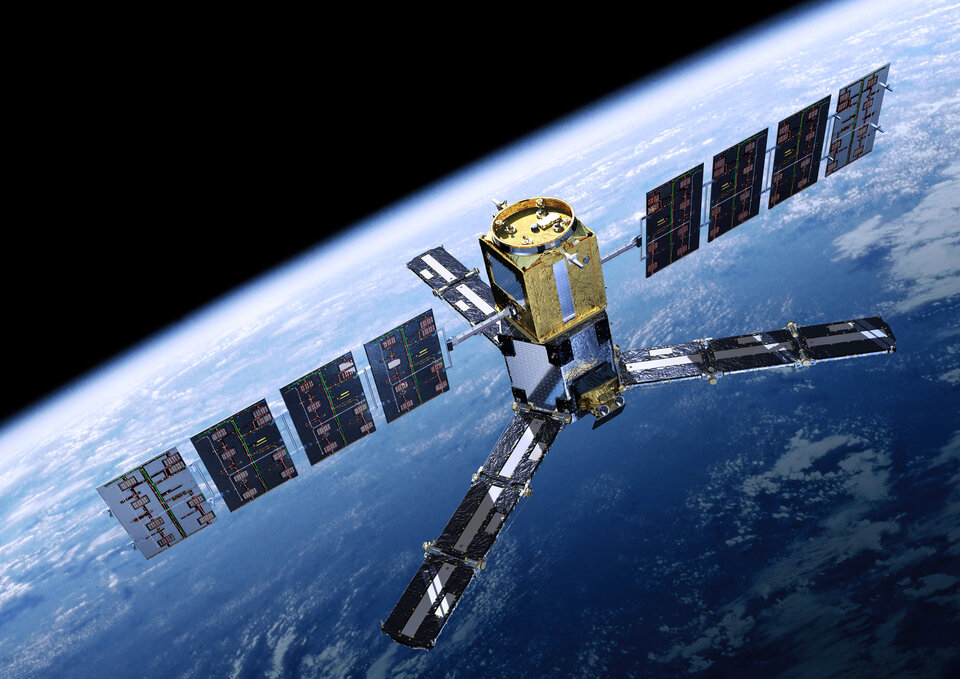

Satellites can monitor the conditions that can lead to swarming locusts, such as soil moisture and green vegetation. ESA recently teamed up with international partners from Algeria, France, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Spain and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to test how data from satellites such as ESA’s Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity mission – or SMOS – can be used to predict locust plagues.

“At FAO, we have a decades-long track record of forecasting plagues and working closely with countries at greatest risk to implement control measures,” said Keith Cressman, FAO’s Senior Locust Forecasting Officer.

“By bringing our expertise together with ESA’s satellite capabilities we can significantly improve timely and accurate forecasting. Early warning means countries can act swiftly to control a potential outbreak and prevent massive food losses.”

The SMOS satellite captures images of ‘brightness temperature’ that correspond to radiation emitted from Earth’s surface, which can be used to gain information on soil moisture at a resolution of 50 km per pixel.

By combining this information with medium-resolution coverage from the MODIS instrument on NASA’s Aqua and Terra satellites, the team downscaled SMOS soil moisture to a resolution of 1 km per pixel. The measurements were then used to create maps showing areas with favourable locust swarming conditions about 70 days ahead of the November 2016 outbreak in Mauritania.

In the past, satellite-based locust forecasts were derived from information on green vegetation, meaning the favourable conditions for locust swarms were already present. This allowed for a warning period of only one month.

Information on soil moisture, on the other hand, indicates how much water is available for eventual vegetation growth and favourable locust breeding conditions, and can therefore forecast the presence of locusts 2–3 months in advance. The additional time is essential for the local national authorities to organise preventive measures.

“I use the data products to understand the current situation, as well as the evolution of locust outbreaks,” said Ahmed Salem Benahi, Chief Information Officer for Mauritania’s National Centre for Locust Control.

“We now have the possibility to see the risk of a locust outbreak one to two months in advance, which helps us to better establish preventive control.”

While the current data products are based on the SMOS and MODIS missions, information from the Copernicus Sentinel-3 mission will soon be integrated to ensure the long-term availability of the locust warnings.

The team is also working on a similar product downscaling SMOS soil moisture with Sentinel-1 observations, which will allow a further increase of resolution to 100 m.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland