Angling up for Mars science

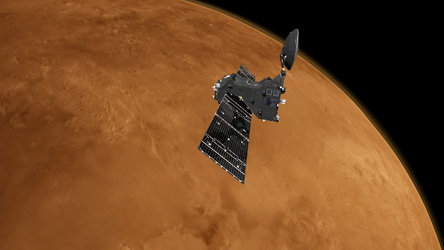

ESA’s latest Mars orbiter has moved itself into a new path on its way to achieving the final orbit for probing the Red Planet.

The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter arrived last October on a multiyear mission to understand the tiny amounts of methane and other gases in the atmosphere that could be evidence for biological or geological activity.

In January, it conducted a series of crucial manoeuvres, firing its main engine to adjust its orbit around Mars.

The three firings shifted its angle of travel with respect to the equator to almost 74º from the 7º of its October arrival. This essentially raised the orbit from equatorial to being much more north–south.

The arrival orbit was set so that it could deliver the Schiaparelli lander to Meridiani Planum, near the equator, with good communications.

Once science observations begin next year, the new 74º orbit will provide optimum coverage of the surface for the instruments, while still offering good visibility for relaying data from current and future landers.

Mission controllers at work

The change was achieved in three burns on 19, 23 and 27 January, overseen by the mission control team working at ESA’s operations centre in Darmstadt, Germany.

“The manoeuvres were performed using the main engine in three steps to avoid a possible situation where the spacecraft could end up on a collision course with Mars in case of any unexpected early termination or underperformance of the engine,” said spacecraft operations manager Peter Schmitz.

Peter notes the engine delivered very precise levels of thrust: “All three were completed to within just a few tenths of a percent of the target thrust, resulting in the craft’s orbital plane being off by just a few fractions of a degree, which is trivial.”

A final, minor trim was made on 5 February, at the same time lowering the altitude above Mars at closest approach from 250 km to 210 km.

Atmospheric drag

The inclination change was also a necessary step for the next challenge: a months-long ‘aerobraking’ campaign designed to bring the spacecraft to its near-circular final science orbit, at an altitude of around 400 km.

Mission controllers will command the craft to skim the wispy top of the atmosphere, generating a tiny amount of drag that will steadily pull it down. The process is set to begin in mid-March, and is expected to take about 13 months.

Access the video

Inclination change happens around the 1:05 mark in this animation

Just before aerobraking, in early March, the science teams will have another opportunity to switch on their instruments and make vital calibration measurements from the new orbit. This will add to the test data collected during two dedicated orbits late last year, and is important preparation for the main science mission.

The main scientific goal is to build a detailed inventory of rare gases that make up less than 1% of the atmosphere’s volume, including methane, water vapour, nitrogen dioxide and acetylene.

Of high interest is methane, which on Earth is produced primarily by biological activity, and to a smaller extent by geological processes such as some hydrothermal reactions.

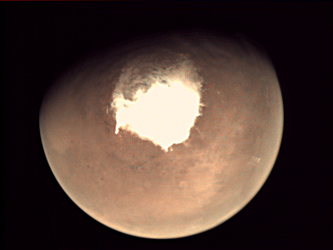

The spacecraft will also seek out water or ice just below the surface, and will provide colour and stereo context images of surface features, including those that may be related to possible trace gas sources.

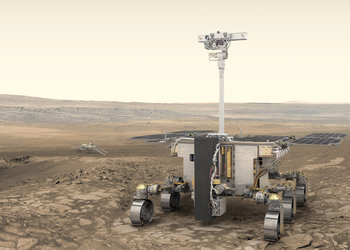

The orbiter will also act as a data relay for present and future landers and rovers on Mars, including the second ExoMars mission that will feature a rover and surface science platform, for launch in 2020.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland