Surfing complete

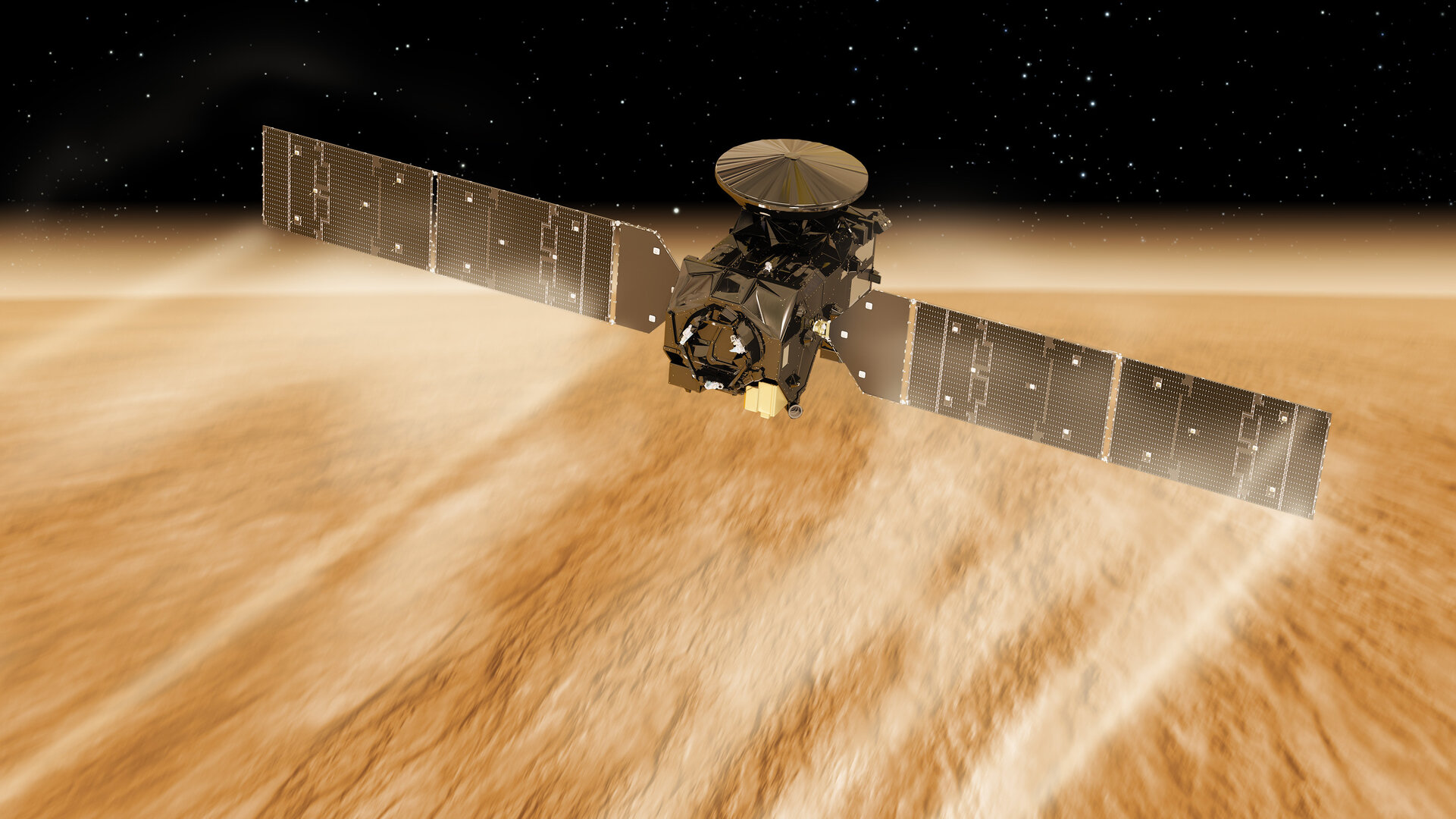

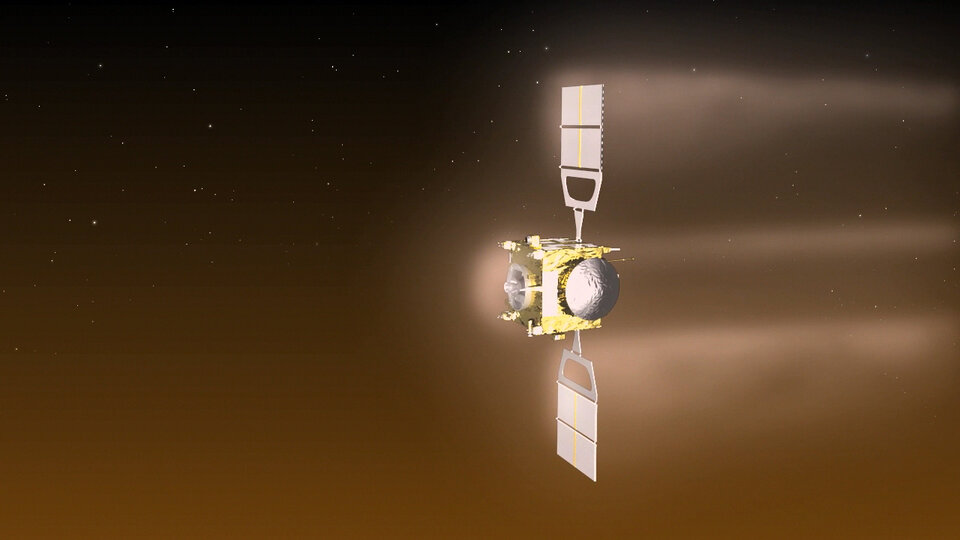

Slowed by skimming through the very top of the upper atmosphere, ESA’s ExoMars has lowered itself into a planet-hugging orbit and is about ready to begin sniffing the Red Planet for methane.

The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter arrived at Mars in October 2016 to investigate the potentially biological or geological origin of trace gases in the atmosphere.

It will also serve as a relay, connecting rovers on the surface with their controllers on Earth.

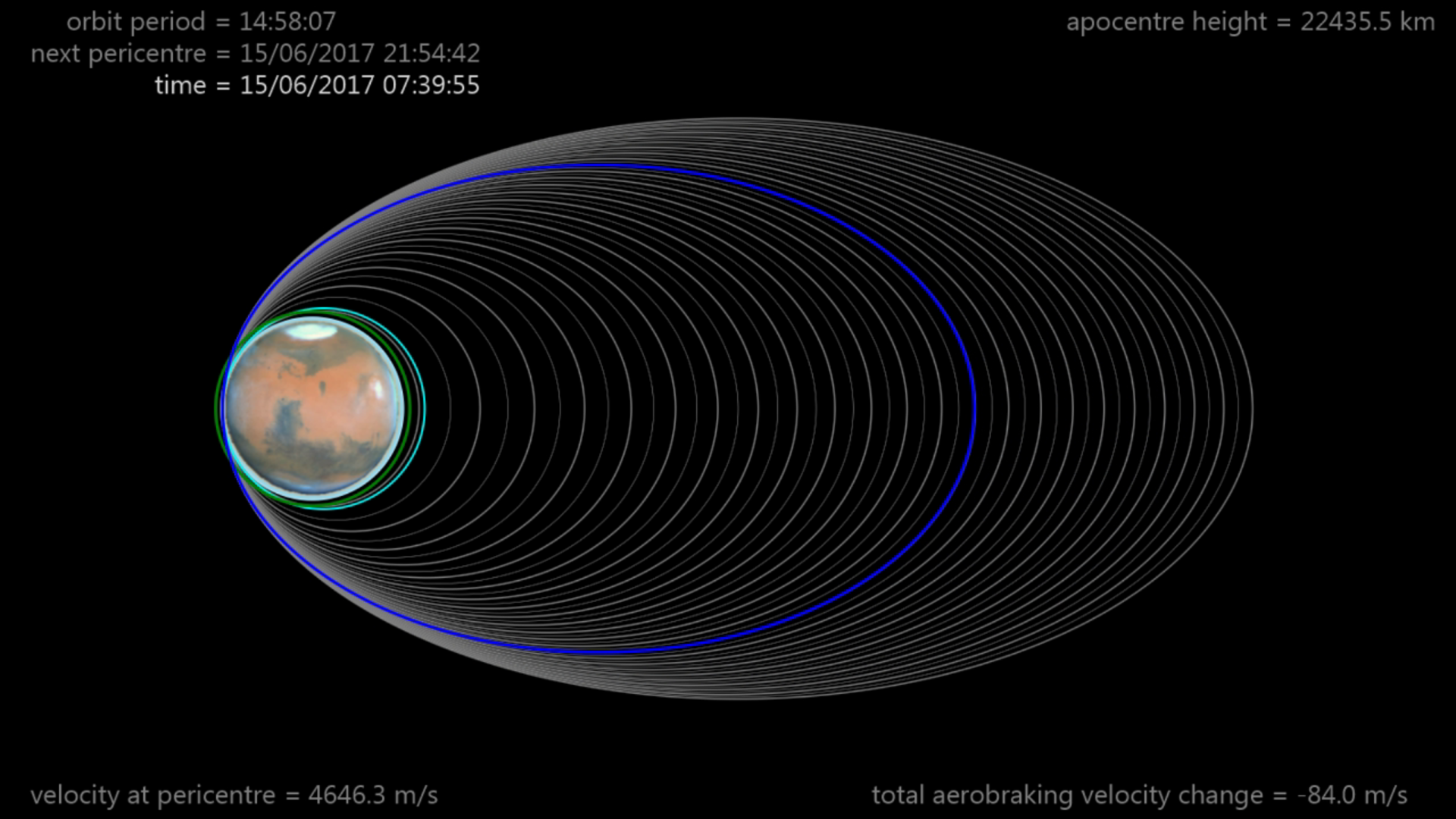

But before any of this could get underway, the spacecraft had to transform its initial, highly elliptical four-day orbit of about 98 000 x 200 km into the final, much lower and circular path at about 400 km.

Terrifically delicate

“Since March 2017, we’ve been conducting a terrifically delicate ‘aerobraking’ campaign, during which we commanded it to dip into the wispy, upper-most tendrils of the atmosphere once per revolution, slowing the craft and lowering its orbit,” says ESA flight director Michel Denis.

Access the video

“This took advantage of the faint drag on the solar wings, steadily transforming the orbit. It’s been a major challenge for the mission teams supported by European industry, but they’ve done an excellent job and we’ve reached our initial goal.

“During some orbits, we were just 103 km above Mars, which is incredibly close.”

The end of this effort came at 17:20 GMT on 20 February, when the craft fired its thrusters for about 16 minutes to raise the closest approach to the surface to about 200 km, well out of the atmosphere. This effectively ended the aerobraking campaign, leaving it in an orbit of about 1050 x 200 km.

Employing interplanetary experience

“We already acquired experience with aerobraking on a test basis at the end of the Venus Express mission, which was not designed for aerobraking, in 2014,” says spacecraft operations manager Peter Schmitz.

“But this is the first time ESA has used the technique to achieve a routine orbit around another planet – and ExoMars was specifically designed for this.”

Aerobraking around an alien planet that is, typically, 225 million km away is an incredibly delicate undertaking. The thin upper atmosphere provides only gentle deceleration – at most some 17 mm/s each second. How small is this?

If you braked your car at this rate from an initial speed of 50 km/h to stop at a junction, you’d have to start 6 km in advance.

“Aerobraking works only because we spent significant time in the atmosphere during each orbit, and then repeated this over 950 times,” says Michel.

“Over a year, we’ve reduced the speed of the spacecraft by an enormous 3600 km/h, lowering its orbit by the necessary amount.”

Trimming

In the next month, the control team will command the craft through a series of up to 10 orbit-trimming manoeuvres, one every few days, firing its thrusters to adjust the orbit to its final two-hour, circular shape at about 400 km altitude, expected to be achieved around mid-April.

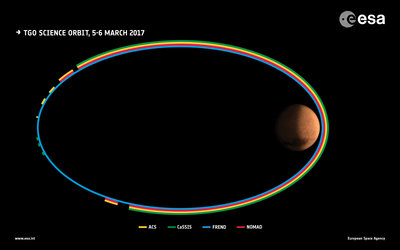

The initial phases of science gathering, in mid-March, will be devoted to checking out the instruments and conducting preliminary observations for calibration and validation. The start of routine science observations should happen around 21 April.

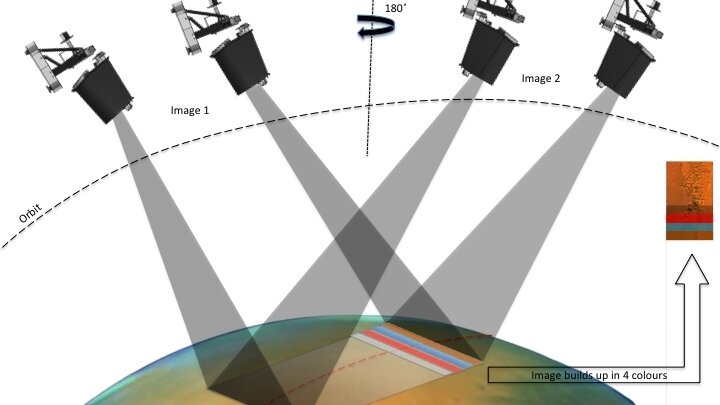

“Then, the craft will be reoriented to keep its camera pointing downwards and its spectrometers towards the Sun, so as to observe the Mars atmosphere, and we can finally begin the long-awaited science phase of the mission,” says Håkan Svedhem, ESA’s project scientist.

The main goal is to take a detailed inventory of trace gases, in particular seeking out evidence of methane and other gases that could be signatures of active biological or geological activity.

A suite of four science instruments will make complementary measurements of the atmosphere, surface and subsurface. Its camera will help to characterise features on the surface that may be related to trace-gases sources, such as volcanoes.

It will also look for water-ice hidden just below the surface, which along with potential trace gas sources could guide the choice for future mission landing sites.

Long-distance calls

April will also see the craft test its data-relay capability, a crucial aspect of its mission at Mars.

A NASA-supplied radio relay payload will catch data signals from US rovers on the surface and relay these to ground stations on Earth. Data relaying will get underway on a routine basis later in the summer.

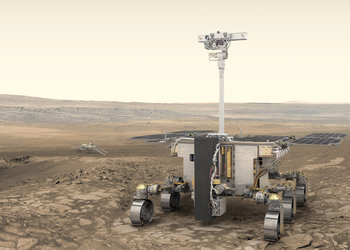

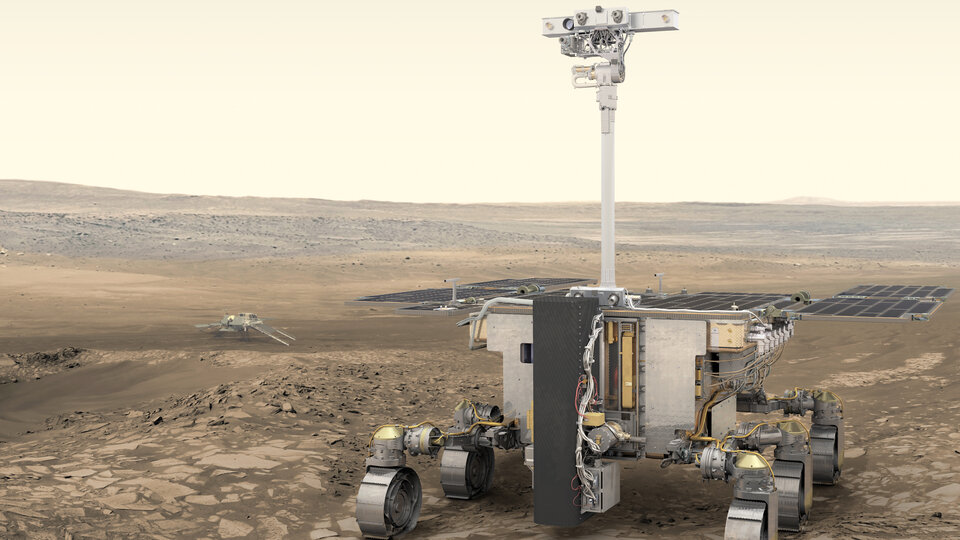

Starting in 2021, once ESA’s own ExoMars rover arrives, the orbiter will provide data-relay services for both agencies and for a Russian surface science platform.

ExoMars is a joint endeavour between ESA and Roscosmos.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland