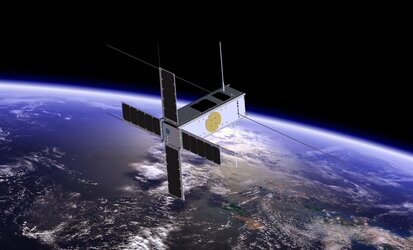

3D printing CubeSat bodies for cheaper, faster missions

As a first test of a new printable hard, electrically conductive plastic, ESA has 3D-printed CubeSat structures incorporating their own electrical lines. In future, such miniature satellites could be ready to go once their instruments, circuit boards and solar panels were slotted in.

“We’ve been looking into 3D printing using ‘polyether ether ketone’ – or PEEK,” explains ESA’s Ugo Lafont.

“PEEK is a thermoplastic with very good intrinsic properties in terms of strength, stability and temperature resistance, with a melting point up around 350ºC. PEEK is so robust that it can do comparable jobs to some metal parts.

“We started a project with Portuguese company PIEP and, in a technical first, we made this printable PEEK electrically conductive by adding certain nano-fillers to the material.

“This kind of customising has taken place for as long as the plastic industry has existed. Plastic has been mixed with different materials to tailor their properties as desired, to make them more resistant for instance, or shinier. In this instance, this ‘doped’ PEEK filament can now be used as a standard feedstock in our 3D printing process.”

As a demonstration of this breakthrough, Ugo and intern Stefan Siarov from TU Delft in the Netherlands decided to print bodies for CubeSats.

These are cheap nanosatellites literally in a box: they are based on rugged, stackable electronic boards housed in one or more standardised 10 cm units. First developed as educational tools, CubeSats are increasingly being put to active uses in orbit.

“The resulting PEEK CubeSat structures would be capable of flying in space,” comments Stefan. “But these bodies are also functional, because they incorporate electrically conductive lines in place of the wire harness normally connecting up the different CubeSat subsystems.”

As a next step, the Materials’ Physics & Chemistry team is collaborating with ESA’s Directorate of Human Spaceflight and Robotic Exploration on a space-optimised PEEK printer for initial testing on ‘zero-g’ aircraft flights, then eventually at the service of astronauts on the International Space Station.

“The vision we have to enable a new maintenance strategy,” adds Ugo. “Rather than just making toys with no added value, PEEK and comparable thermoplastics are robust enough to find a lot of practical uses, plus the added option of electrical functionality.

“Space Station crews end up needing all kinds of items, all of which currently require transport from Earth: everything from screws and water valves to hermetic containers and water valves. All of these could be 3D-printed instead – even toothbrushes – since PEEK is biocompatible.

“3D-printing such items in orbit would be cheaper, and would change the equation of recyclability. Because these plastic items can later be recycled, we reduce the scarcity of materials in space and start to make human missions to space more self-sustaining.”

Stefan meanwhile is now assessing the recyclability of other 3D-printed engineering thermoplastics at ESA’s European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, Germany.

“We have been taking a continuing interest into high-performance thermoplastic materials over the last decade,” comments Christopher Semprimoschnig, heading ESA’s Materials’ Physics and Chemistry Section. “The freedom that new processing options such as 3D printing offer are especially intriguing for ESA.”

Reflecting the relative maturity of this 3D-printed material, a small PEEK-printed structural part is due to fly on the Meteosat Third Generation series of weather satellites at the end of this decade.

Access the video

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland