ESA spacecraft dodges large constellation

- For the first time, ESA has performed a 'collision avoidance manoeuvre' to protect one of its spacecraft from colliding with a satellite in a large constellation.

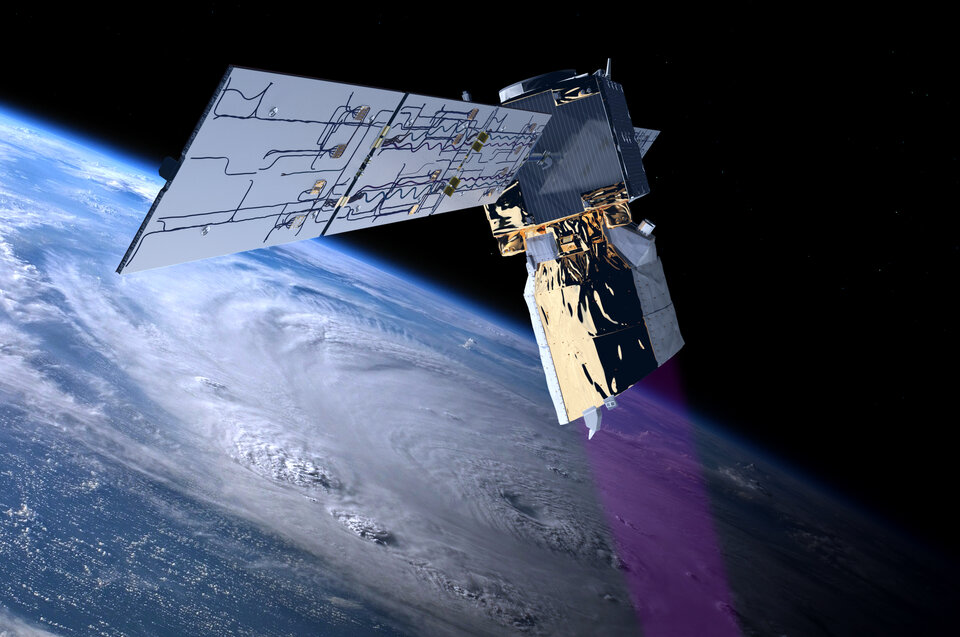

- On Monday morning, the Agency's Aeolus Earth observation satellite fired its thrusters, moving it off a potential collision course with a SpaceX satellite in the Starlink constellation.

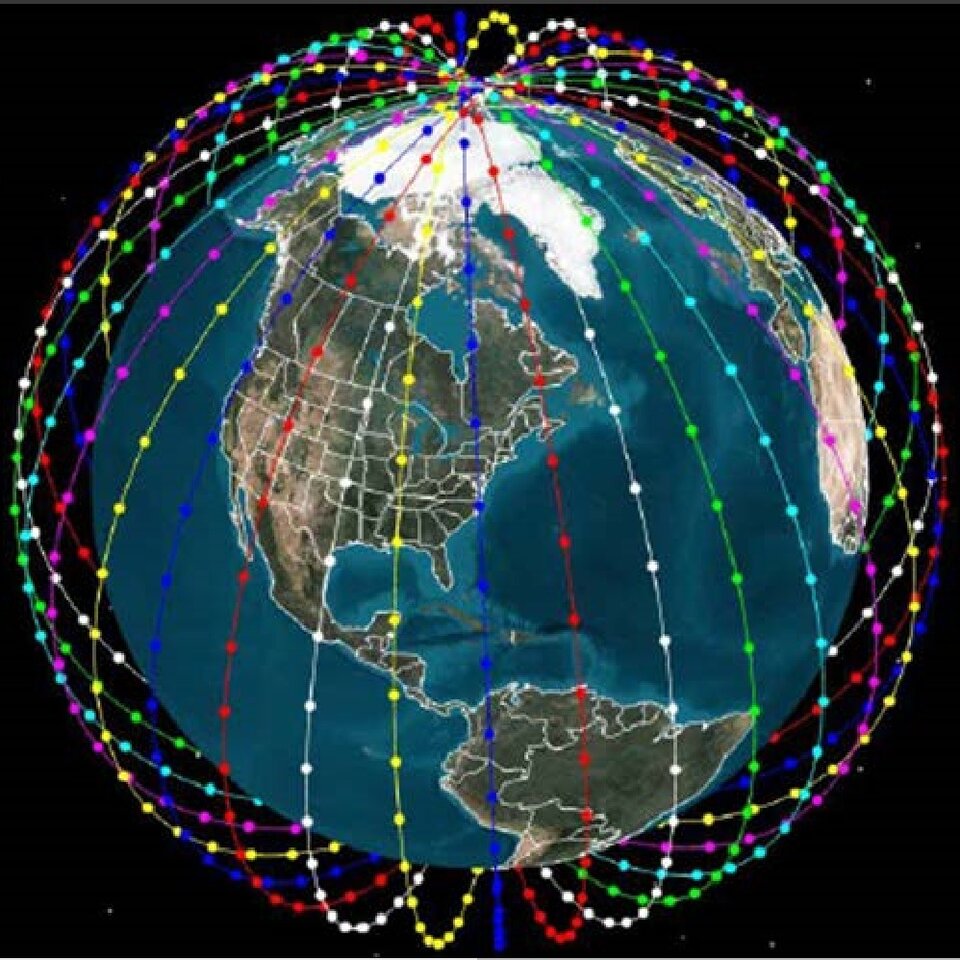

- Constellations are fleets of hundreds up to thousands of spacecraft working together in orbit. They are expected to become a defining part of Earth’s space environment in the next few years.

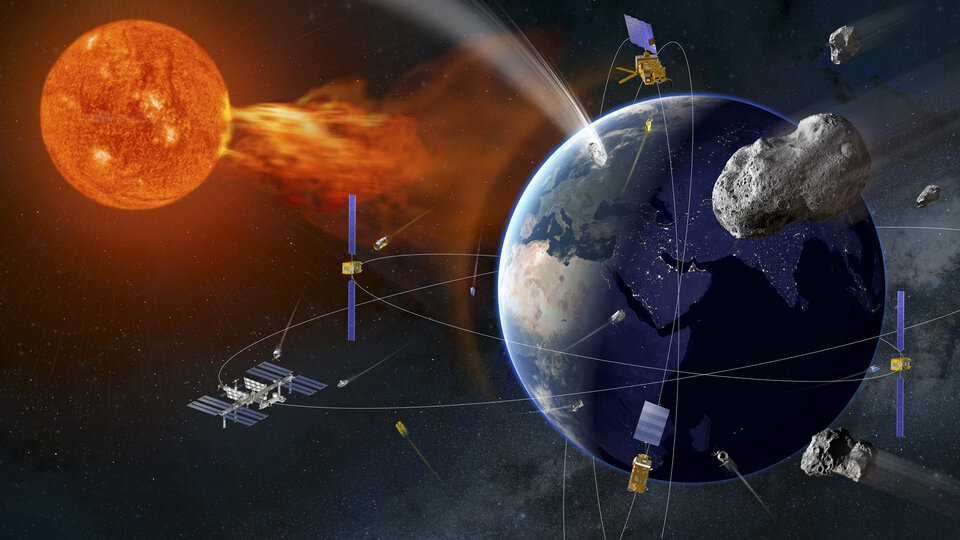

- As the number of satellites in space dramatically increases, close approaches between two operated spacecraft will occur more frequently. Compared with such 'conjunctions' with space debris – non-functional objects including dead satellites and fragments from past collisions – these require coordination efforts, to avoid conflicting actions.

- Today, the avoidance process between two operational satellites is largely manual and ad hoc – and will no longer be practical as the number of alerts rises with the increase in spaceflight.

-

“This example shows that in the absence of traffic rules and communication protocols, collision avoidance depends entirely on the pragmatism of the operators involved,” explains Holger Krag, Head of Space Safety at ESA.

“Today, this negotiation is done through exchanging emails - an archaic process that is no longer viable as increasing numbers of satellites in space mean more space traffic.”

- ESA is proposing an automated risk estimation and mitigation initiative as part of its space safety activities. This will provide and demonstrate the types of technology needed to automate the collision avoidance process, allowing machine generated, coordinated and conflict-free manoeuvre decisions to speed up the entire process – something desperately needed to protect vital space infrastructure in the years to come.

What happened?

Data is constantly being issued by the 18th Space Control Squadron of the US Air Force, who monitor objects orbiting in Earth’s skies, providing information to operators about any potential close approach.

With this data, ESA and others are able to calculate the probability of collision between their spacecraft and all other artificial objects in orbit.

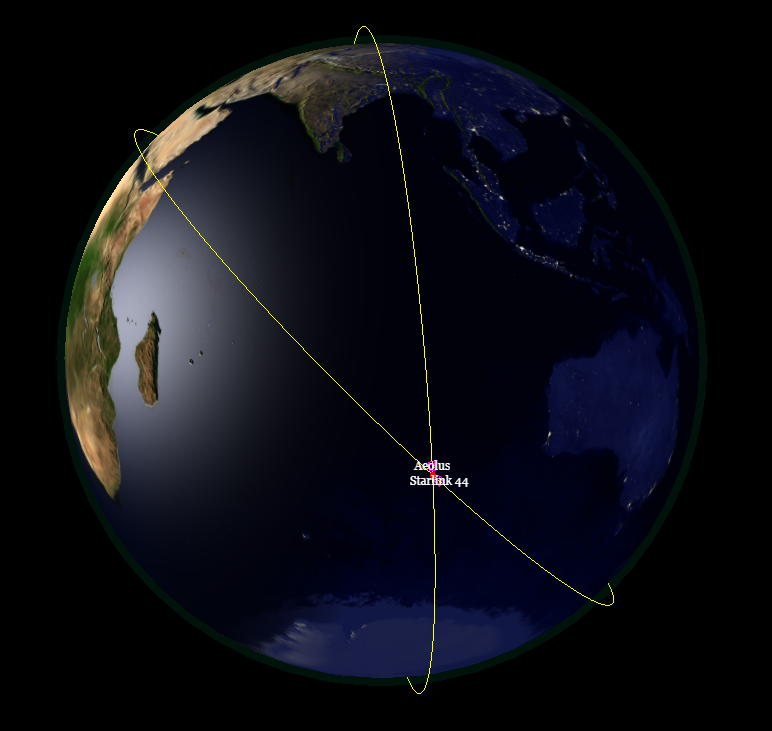

About a week ago, the US data suggested a potential ‘conjunction’ at 11:02 UTC on Monday, 2 September, between ESA’s Aeolus satellite and Starlink44 – one of the first 60 satellites recently launched in SpaceX’s mega constellation, planned to be a 12 000 strong fleet by mid-2020.

Experts in ESA’s Space Debris Office worked to calculate the collision probability, combining information on the expected miss distance, conjunction geometry and uncertainties in orbit information.

As days passed, the probability of collision continued to increase, and by Wednesday 28 August the team decided to reach out to Starlink to discuss their options. Within a day, the Starlink team informed ESA that they had no plan to take action at this point.

ESA’s threshold for conducting an avoidance manoeuvre is a collision probability of more than 1 in 10 000, which was reached for the first time on Thursday evening.

An avoidance manoeuvre was prepared which would increase Aeolus’ altitude by 350 m, ensuring it would comfortably pass over the other satellite, and the team continued to monitor the situation.

On Sunday, as the probability continued to increase, the final decision was made to implement the manoeuvre, and the commands were sent to the spacecraft from ESA’s mission control centre in Germany.

At this moment, chances of collision were around 1 in 1000, 10 times higher than the threshold.

On Monday morning, the commands triggered a series of thruster burns at 10:14, 10:17 and 10:18 UTC, half an orbit before the potential collision.

About half an hour after the conjunction was predicted, Aeolus contacted home as expected. This was the first reassurance that the manoeuvre was correctly executed and the satellite was OK.

Since then, teams on the ground have continued to receive scientific data from the spacecraft, meaning operations are back to normal science-gathering mode.

Contact with Starlink early in the process allowed ESA to take conflict-free action later, knowing the second spacecraft would remain where models expected it to be.

New space

Since the first satellite launch in 1957, more than 5500 launches have lifted over 9000 satellites into space. Of these, only about 2000 are currently functioning, which explains why 90% of ESA’s avoidance manoeuvres are the result of derelict and uncontrollable ‘space debris’.

In the years to come, constellations of thousands of satellites are set to change the space environment, vastly increasing the number of active, operational spacecraft in orbit.

This new technology brings enormous benefits to people on Earth, including global internet access and precise location services, but constellations also bring with them challenges in creating a safe and sustainable space environment.

Space rules

“No one was at fault here, but this example does show the urgent need for proper space traffic management, with clear communication protocols and more automation,” explains Holger.

“This is how air traffic control has worked for many decades, and now space operators need to get together to define automated manoeuvre coordination.”

Autonomous spaceflight

As the number of satellites in orbit rapidly increases, today's 'manual' collision avoidance process will become impossible, and automated systems are becoming necessary to protect our space infrastructure.

Collision avoidance manoeuvres take a lot of time to prepare – from determining the future orbital positions of functioning spacecraft, to calculating the risk of collision and the many possible outcomes of different actions.

ESA is preparing to automate this process using artificial intelligence, speeding up the processes of data crunching and risk analysis, from the initial warning of a potential conjunction to the satellite finally moving out of the way.

Such use of space-based communication links can save precious time when sending manoeuvre commands at the last minute.

Under its Space Safety activities, ESA plans to invest in technologies required to automatically process collision warnings, coordinate manoeuvres with other operators and send the commands to spacecraft entirely automatically, ensuring the benefits of space can continue to be enjoyed for generations to come.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland