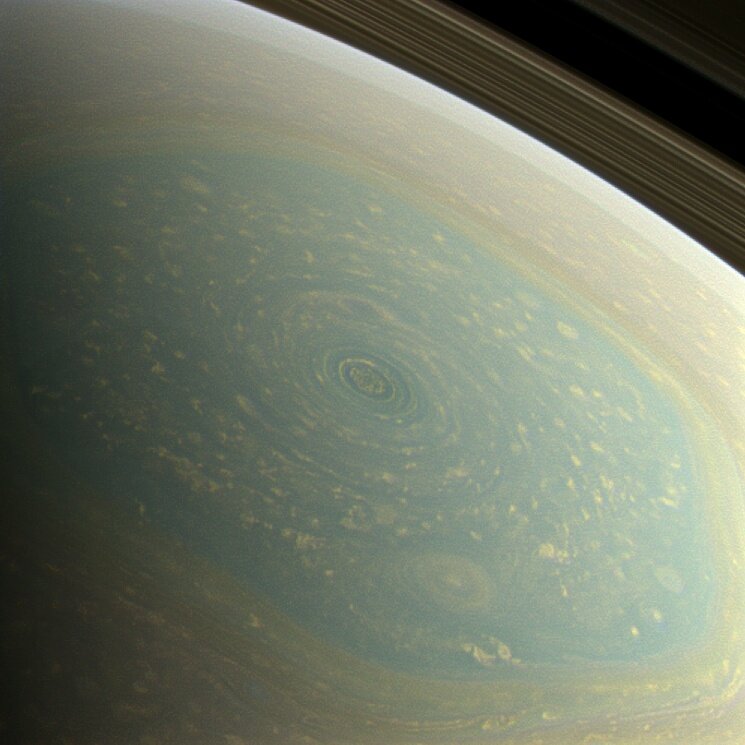

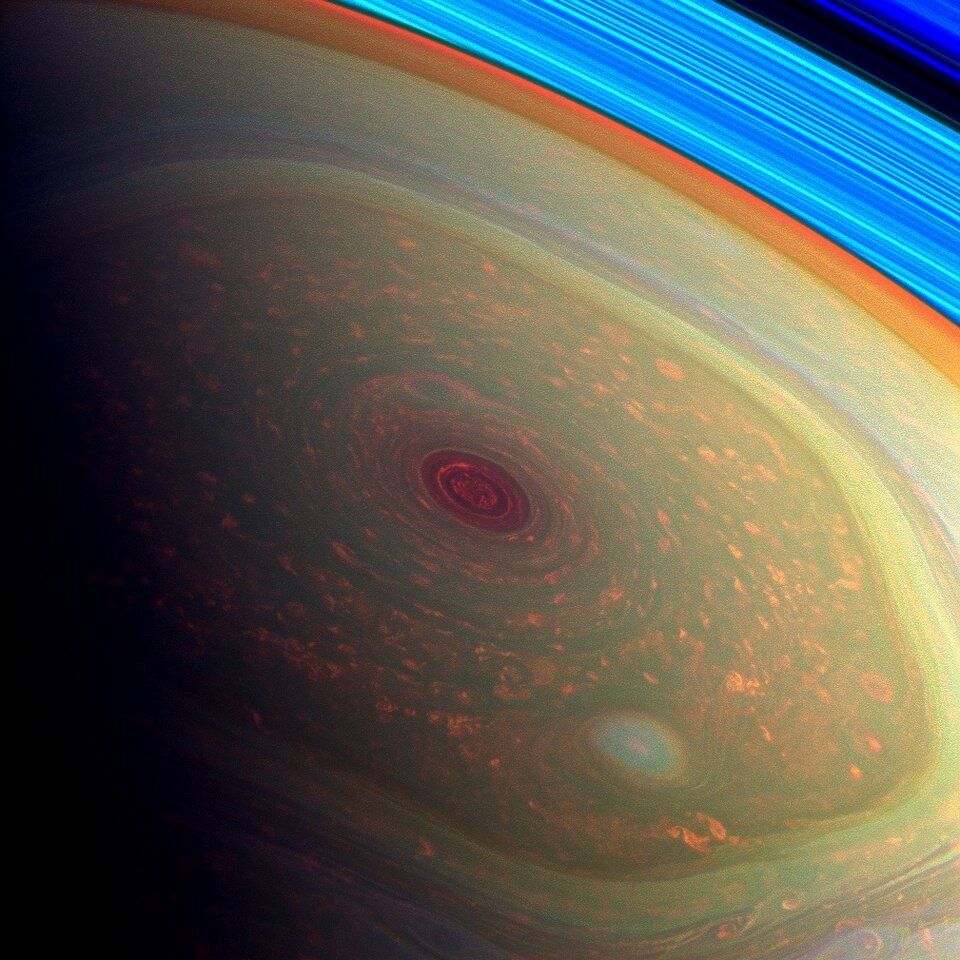

Cassini eyes Saturn hurricane

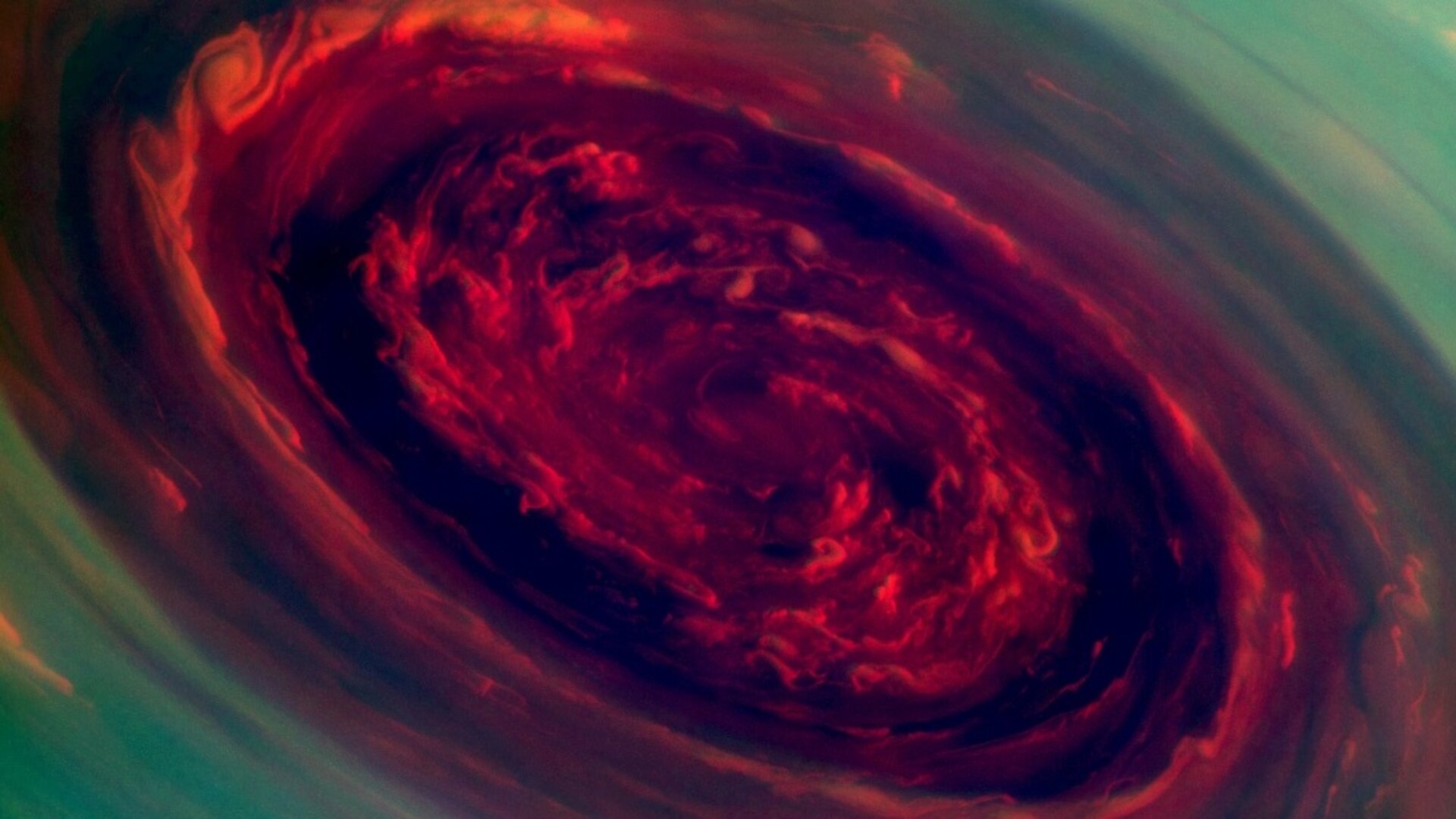

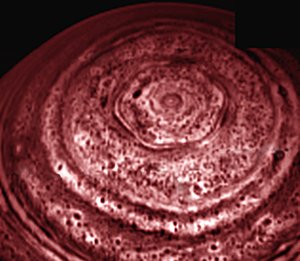

The international Cassini spacecraft has found a powerful hurricane at Saturn's north pole, surrounded by the curious rotating hexagonal band of clouds.

The images were taken by Cassini’s camera on 27 November 2012 and are the first close-up views of this storm, which has been churning since at least 2006.

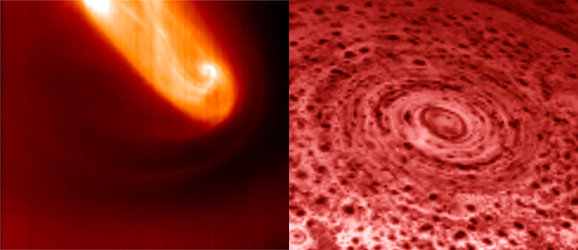

NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft did not have a clear view of this part of Saturn's north pole when it flew by in 1981, although it did observe the hexagonal band of clouds that is wide enough to fit almost four Earths inside.

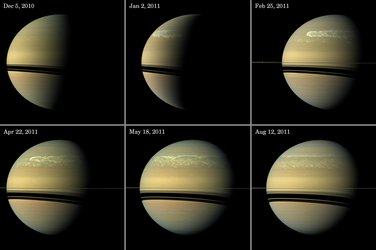

When Cassini arrived in 2004, Saturn’s north pole was dark because it was the middle of its winter. A visible-light view had to wait for the passing of the equinox in August 2009.

Only then did sunlight begin flooding Saturn’s northern hemisphere. The view also required a change in the angle of Cassini’s orbits around Saturn so the spacecraft could see the poles.

In high-resolution pictures and a movie, scientists see that the extent of the hurricane's eye stretches some 2000 km across. The hurricane – 20 times larger than the average hurricane eye on Earth – has thin, bright clouds at the outer edge travelling at 540 km/h. The eyewall winds blow more than four times faster than hurricane force winds on Earth.

The hurricane looks uncannily like those we see on Earth, but on a much larger – and faster – scale. But there are also some remarkable differences.

Strangely, the Saturnian hurricane is locked onto the planet’s north pole. On Earth, hurricanes tend to drift towards the poles, but the Saturn hurricane is as far north as it can travel, and is likely stuck there.

Furthermore, Earth’s hurricanes are powered by warm ocean water, but the Saturn storm is somehow getting by on the small amounts of water vapour in the planet’s hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

Learning how these Saturnian storms use the water vapour available to them could tell scientists more about how terrestrial hurricanes are generated and sustained.

Notes for Editors

The images were taken by Cassini on 27 November 2012 from a distance of 418 000 – 419 000 km.

Cassini flies a set of inclined orbits only every few years. The orbit tracks require precise oversight from navigators because the spacecraft uses flybys of Saturn’s moon Titan to change the angle of Cassini’s orbit. This path requires careful planning years in advance and sticking very precisely to the planned itinerary to ensure enough propellant is available for the spacecraft to reach future planned orbits and encounters.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA and Italy’s ASI space agency. JPL manages the Cassini–Huygens mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington DC, USA. The Cassini orbiter and its two cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging team consists of scientists from the United States, England, France and Germany. The imaging operations centre is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland