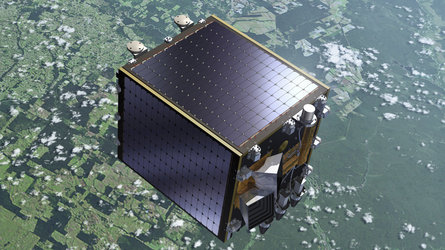

Year-old Proba-V charting global greenery

A year after its launch, ESA’s Proba-V is set to make a giant leap for a minisatellite: formally taking over the task of continuously charting our planet’s global vegetation.

For 5880 days – 16 years in all – the Vegetation cameras on France’s full-sized Spot-4 and Spot-5 satellites have been monitoring plant growth across Earth, compiling a new global map every two days.

Scientific teams around the world use these sensors to predict crop yields, chart the progress of drought and desertification, pinpoint deforestation and improve climate change models.

But Spot-4 stopped operating last year and Spot-5 is nearing the end. The torch will shortly be passed to Proba-V, ESA’s latest minisatellite, launched on 7 May last year.

On 30 May Proba-V’s own Vegetation camera will formally take over the task of collecting this information from Spot-5.

The two instruments enjoyed a one-year overlap, which has allowed detailed cross-calibration between the two, ensuring a consistent time series for scientists to employ seamlessly.

“Proba-V’s new job is a notable first for a small satellite,” explained Bianca Hoersch, ESA’s Proba-V Mission Manager.

“At less than a cubic metre, the entire satellite is actually compact enough to fit inside the former generation of Vegetation sensors, which were housed aboard the van-sized Spot satellites.”

This new generation had to be extensively redesigned to fit aboard ESA’s minisatellite, while retaining the wide 2250 km field of view that allows it to chart all vegetation every two days.

At the same time, the redesign also sharpened its acuity considerably, from 1 km to 300 m, down to 100 m in its central swath.

Proba-V was designed and built rapidly by a Belgian consortium of companies, specifically to serve as a gapfiller between Spot and ESA’s coming Sentinel-3 mission.

The latest in ESA’s ‘Project for Onboard Autonomy’ satellite family, Proba-V is not only one of the smallest missions in space but also the smartest.

The high-performance satellite requires minimal human involvement. For example, its fully autonomous navigation means it can change orientation while automatically avoiding hazards such as turning towards sunlight which might blind its camera.

And its flight computer, developed by mission prime contractor QinetiQ Space in Belgium, stores data using solid state flash memory, more typically found in consumer USB sticks, digital cameras and mobile phones.

This is a tenfold improvement on previous techniques, allowing the satellite to store imagery for half the world between its 10-times-per-day data downlinks to the ground.

“And, as with the previous Proba missions, the satellite also hosts extra technology payloads,” added ESA’s Karim Mellab, who oversaw the mission’s flight preparations.

“These are experimental hardware that have proved themselves in orbit, with some significant world firsts among them.”

These include the very first space-based monitoring system for air traffic, picking up signals which are planned to take the place of ground-based radar tracking.

Proba-V’s receiver was only supposed to operate periodically but the satellite’s power availability has been good enough to keep it running continuously.

And an experimental radio-frequency amplifier built from gallium nitride – a high-power semiconductor widely described as the most promising material of its kind since silicon – is now used routinely to downlink data, boosting the flexibility and redundancy of Proba-V’s communication system.

A pair of radiation detectors is helping to map a mysterious ‘hole’ in Earth’s magnetic field, called the South Atlantic Anomaly, in sharper detail than ever before.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland