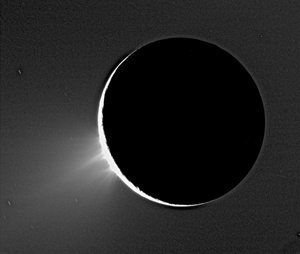

Geysers on Saturn’s moon Enceladus indicate liquid water

The NASA/ESA/ASI Cassini spacecraft has observed water-vapour plumes in the south-polar region of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. The plumes, resembling geysers on Earth, may be linked to the existence of underground reservoirs of liquid water.

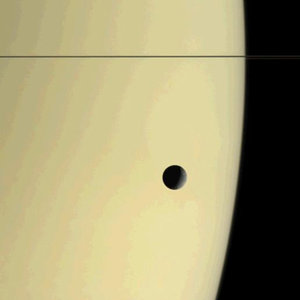

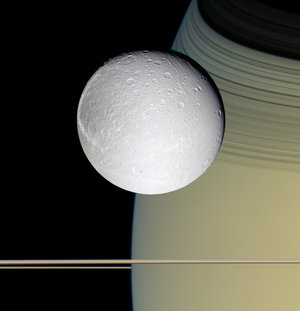

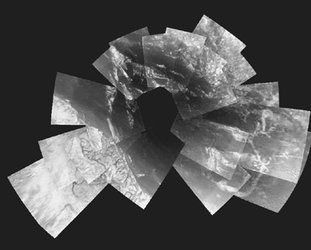

Cassini flew by Enceladus three times, in January, February and July 2005. During the observations of this icy moon, the sixth largest Saturnian satellite, Cassini’s instruments recorded the presence of icy jets and towering plumes ejecting large quantities of particles at high speed.

Cassini’s data show that the ejections, localised in a confined region of the south pole, are dominated by the presence of water, with significant amounts of carbon dioxide and methane.

In parallel, Cassini’s instruments also detected evidence for ongoing internal activity just below the region where the jets are observed. In fact, it measured thermal emissions from south polar troughs, that make Enceladus the only third known planetary body – after Earth and Jupiter’s moon Io – that is sufficiently geologically active for its internal heat to be detected by remote-sensing instruments.

Combining all data, scientists have made hypotheses and examined several models to explain the plumes’ process. They ruled out the idea that the particles are produced by or blown off the moon’s surface by vapour created when warm water ice converts to a gas.

Instead, scientists have found evidence for a much more exciting possibility - the jets might be erupting from near-surface pockets of liquid water above 0°C. Furthermore, the pockets of liquid water may be no more than tens of metres below the surface.

The presence of such hydrothermal activity may give meaning to other unexplained oddities. In fact, as Cassini approached Saturn, it discovered that the Saturnian system - especially Saturn’s E-ring in which Enceladus is embedded, is filled with oxygen atoms.

"At the time we had no idea where the oxygen was coming from," said Dr Candy Hansen, Cassini scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Now we know that that Enceladus is spewing out water molecules, which break down into oxygen and hydrogen."

Scientists are also seeing variability of the plumes activities at Enceladus. "Even when Cassini is not flying close to Enceladus, we can detect that the plume’s activity has been changing through its varying effects on the soup of electrically-charged particles that flow past the moon," said Dr Geraint Jones, of the Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument (MIMI) team, Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Germany.

Scientists still have many questions. Why is Enceladus currently so active? Are other sites on Enceladus active? Might this activity have been continuous enough over the moon’s history for life to have had a chance to take hold in the moon’s interior?

In the spring of 2008, scientists will get another chance to look at Enceladus when Cassini flies within 350 kilometres, but much work remains after Cassini’s four-year prime mission is over.

"The Cassini Project team may be looking at ways to fly even lower 350 kilometres, using the excellent capabilities of Cassini to react to discoveries," said Jean-Pierre Lebreton, ESA Huygens Project Scientist.

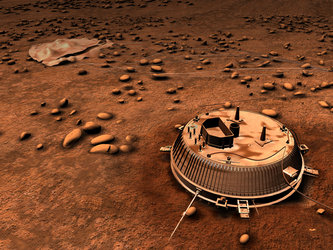

"There’s no question that, along with the moon Titan, Enceladus should be a very high priority for us. Saturn has given us two exciting worlds to explore," concluded Jonathan Lunine, Cassini and Huygens interdisciplinary scientist, University of Arizona (USA).

Note to editors:

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a co-operative project of NASA, ESA and ASI, the Italian space agency.

Mission scientists report these and other Enceladus findings in the 10 March 2006 issue of the scientific journal Science.

For more information:

Jean-Pierre Lebreton, ESA Huygens Mission Manager

Tel: +31 (0)71 565 3600

Jonathan Lunine, Cassini-Huygens interdisciplinary scientist

University of Arizona, USA

E-mail: jlunine @ lpl.arizona.edu

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland