The sounds of Titan

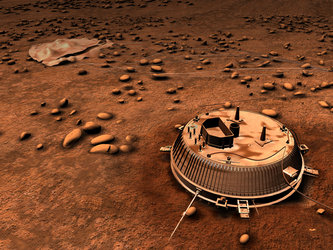

The sound of alien thunder, the patter of methane rain and the crunch (or splash) of a landing, all might be heard as Huygens descends to the surface of Titan on 14 January 2005.

What’s more, they will be recorded by a microphone on the probe and relayed back so that everyone on Earth can hear the sounds of Titan. Although the Russians took a microphone to Venus in the 1970s, few scientific results came out if that endeavour. A similar microphone for Mars was destroyed when NASA’s Mars Polar Lander crashed a few years ago.

The new microphone is part of the Huygens Atmospheric Structure Instrument (HASI), one of six multi-functional experiments carried on the Huygens probe. It is designed to help track down lightning by listening for the clap of thunder usually associated with such an event.

Although there is only a small chance that the spacecraft will pass near a thunderstorm, it is an extremely important investigation to carry out. It may help us to understand if thunderstorms are an important energy source for organic chemistry on Titan.

This may hold clues about how life began on Earth. Titan’s atmosphere is laced with chemicals and many scientists think these are the same as those that formed the building blocks of life on Earth, 4000 million years ago. But how did they join together on Earth to ultimately become DNA?

One possibility is that sudden discharges of energy, as occur in lightning, could have forced the simple chemicals together, making more complicated ones. So Huygens will listen for thunder and ‘sniff’ for chemicals that might have been produced in lightning strikes.

In fact, a second microphone experiment can also be found on Huygens. It is part of the Surface Science Package (SSP) and contributes to an experiment to measure the speed of sound in Titan’s atmosphere.

These results present an exciting possibility because if the HASI microphone does hear thunder, electrodes on the same instrument will register the lightning’s electrical discharge and scientists will be able to calculate how close Huygens passed to the storm.

If Huygens actually passes through a storm, the microphone will detect the splash of the rain onto the spacecraft casing. Unlike on Earth, this rain will not be water but probably liquid methane.

Marcello Fulchignoni, of the Universitè Denis Diderot, Paris, is the principal investigator of HASI. He says, “Combined with the camera images, temperature and pressure profiles, and altitude data, the ‘soundtrack’ will provide a fascinating look at the details of the mission’s descent. We will be working hard to bring the voice of Huygens to the public as soon as we can after the descent.”

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland