Philae’s extraordinary comet landing relived

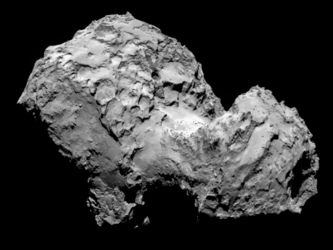

On 12 November 2014, after a ten year journey through the Solar System and over 500 million kilometres from home, Rosetta’s lander Philae made space exploration history by touching down on a comet for the first time. On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of this extraordinary feat, we celebrate Philae’s impressive achievements at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Decisions, decisions

Rosetta arrived at the comet on 6 August 2014, and the race was immediately on to find a suitable landing site for its lander Philae.

The site needed to offer a balance of safety and unique science potential. Rosetta’s images of candidate landing sites were scrutinised and debated, and within a few weeks the final choice was made: a smooth-looking patch, later named Agilkia, located on the smaller of the comet’s two lobes.

Intense preparations followed, but the night before landing, a problem was identified: Philae’s active descent system, which would provide a downward thrust to prevent rebound at touchdown, could not be activated. Philae would have to rely on harpoons and ice screws in its three feet to fix it to the surface.

Nonetheless, the green light was given and after separating from Rosetta, Philae began its seven-hour descent to the surface of the comet. During the descent, Philae began ‘sensing’ the environment around the comet, taking stunning imagery as the first landing site came into view.

Welcome to a comet

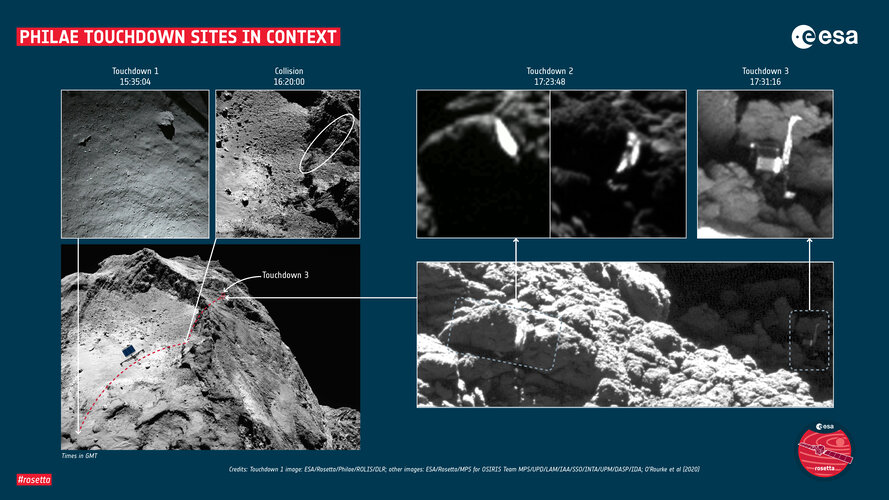

Philae’s touchdown at Agilkia was spot-on. The sensors on Philae’s feet felt the touchdown vibrations, generating the first recording of contact between a human-made object and a comet. But it soon became clear that Philae’s harpoons hadn’t fired and it had taken flight again.

In the end Philae made contact with the surface four times. Thanks to an automatic sequence that was triggered by the first touchdown signal, Philae’s instruments were operating while in flight, collecting unique data that would later yield important results. It was also an unexpected bonus that data were collected at more than one location, providing the first direct measurements of surface characteristics and allowing comparisons between the touchdown sites.

For example, Philae ‘felt’ the difference in surface texture and hardness as it bounced from one site to another. At the first landing site, it detected a soft layer several centimetres thick, milliseconds later encountering a much harder layer.

After colliding with a cliff, Philae scraped through its second touchdown site, providing the first in situ measurement of the softness of the icy-dust interior of a boulder on a comet. The simple action of Philae ’stamping’ an imprint in billions-of-years-old ice revealed the boulder to be fluffier than froth on a cappuccino, equivalent to a porosity of about 75%.

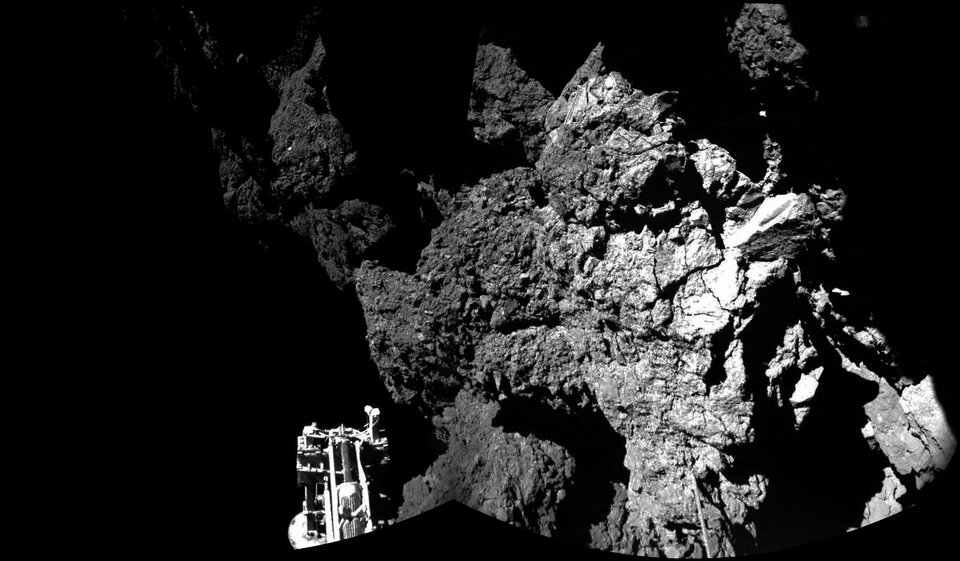

Philae then ‘hopped’ about 30 metres to the final touchdown site, named Abydos, where its CIVA cameras provided the first image of a human-made object touching a 4.6 billion year old Solar System relic. The exact location on the comet would remain hidden from view for almost two years.

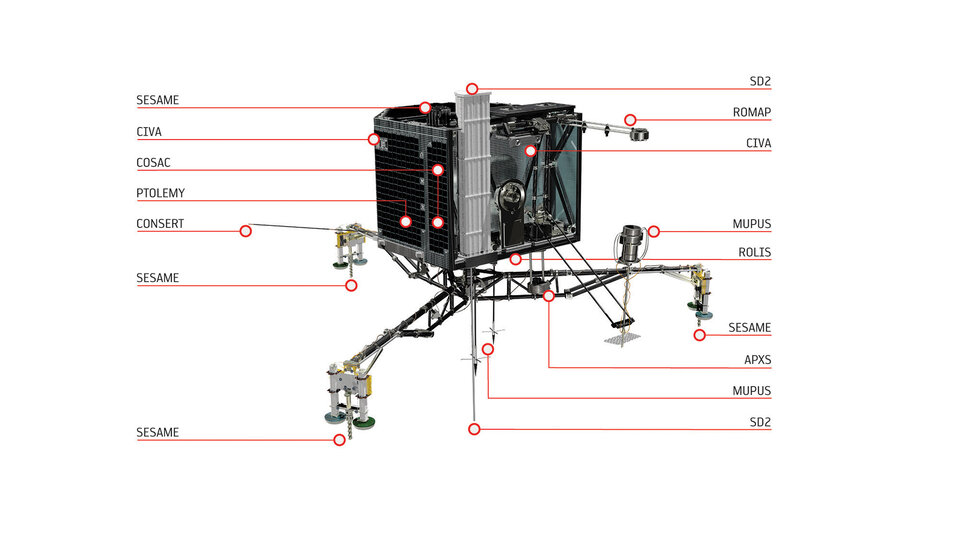

In this location, Philae’s MUPUS hammer penetrated a soft layer before encountering an unexpectedly hard surface a few centimetres below the surface. Philae ‘listened’ to the hammering with its feet, recording the vibrations that passed through the comet. This was the first time since the Apollo 17 mission to the Moon in 1972 that active seismic measurements were conducted on a celestial body.

MUPUS also carried a thermal sensor, which measured the local changes in temperature from about -180ºC to 145ºC, in sync with the comet’s 12.4 hour day – the first time the temperature cycle of a comet had been measured at its surface.

Meanwhile the CONSERT experiment, which passed radio waves between Rosetta and Philae through the comet in the first cometary sounding experiment, revealed the interior of the comet to be a very loosely compacted mixture of dust and ice, with a high porosity of 75–85%.

In-flight science

During the bouncing, Philae’s COSAC and Ptolemy instruments ‘sniffed’ the comet’s gas and dust, important tracers of the raw materials present in the early Solar System. COSAC revealed a suite of 16 organic compounds comprising numerous carbon and nitrogen-rich compounds, including methyl isocyanate, acetone, propionaldehyde and acetamide that had never before been detected in comets. The complex molecules detected by both COSAC and Ptolemy play a key role in the synthesis of the ingredients needed for life.

Philae’s bouncing also allowed it to measure the magnetic field at different heights above the surface, showing the comet is remarkably non-magnetic. Detecting the magnetic field of comets has proven difficult in previous missions, which have typically flown past at high speeds, relatively far from comet nuclei. It took the proximity of Rosetta’s orbit around the comet and the measurements made much closer to and at the surface by Philae, to provide the first detailed investigation of the magnetic properties of a comet nucleus.

In the end some 80% of Philae's planned science sequence was completed in the 64 hours following separation from Rosetta and before the lander fell into hibernation.

While Philae hibernated, Rosetta continued returning an unprecedented wealth of information from the comet as it orbited around the Sun, watching the comet’s activity reach a peak and then slowly subside again. Philae would be heard from briefly in June–July 2015 but could not be reactivated. Then, as Rosetta’s mission was drawing to its planned end with its own daring descent to the surface at a site named Sais, Philae’s final landing site was revealed in orbiter imagery, a final twist in what had become one of the greatest stories of space exploration.

Access the video

What’s next?

ESA has an impressive legacy in small body exploration, with the Rosetta-Philae double-act inspiring the next generation of comet and asteroid-chasers.

ESA’s Giotto mission to fly by Comet Halley in 1986 was the first mission to image a comet surface. The Rosetta mission was a natural next step, becoming the first to orbit a comet, as well as deploying a lander to its surface. Rosetta was also the first to follow a comet around the Sun, monitoring its activity as it made its closest approach to the Sun.

Rosetta paves the way for the upcoming Comet Interceptor mission, which unlike its predecessors, will probe a comet visiting our Solar System for the first time. As such, the comet will contain material that has undergone minimal processing, offering a ‘cleaner’ look at pristine material from the dawn of the Solar System, before it is sculpted by the heat of the Sun. The mission will consist of a primary craft and two probes, providing a multi-angled view of the comet.

ESA is also visiting asteroids, with its flagship ‘planetary defender’ Hera on its way to survey Dimorphos following NASA’s impact experiment to alter its trajectory, a grand-scale test of planetary defence techniques. Hera’s orbit scheme is borrowed directly from Rosetta, and the mission's two smaller satellites carry radar and dust-measuring instruments based on those designed for Rosetta.

Meanwhile Ramses will accompany asteroid Apophis as it makes an exceptionally close flyby of Earth in 2029. And suitcase-sized M-Argo will be the smallest spacecraft to perform its own independent mission in space when it rendezvous with a small near-Earth asteroid later this decade.

Rosetta and Philae’s legacy also lives on in the hearts and minds of people, as revealed in our new online exhibition celebrating this uniquely inspiring mission. We are also reliving the key moments around Philae's landing on the comet and Rosetta team members' experiences on X. Join us by following #CometLandingRelived.

Rosetta was an ESA mission with contributions from its Member States and NASA. Philae was provided by a consortium led by DLR, MPS, CNES and ASI.