Integral disproves dark matter origin for mystery radiation

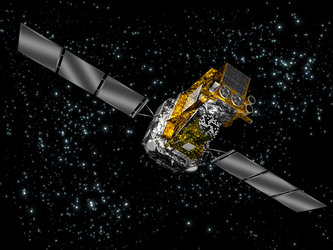

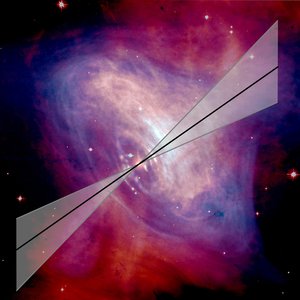

A team of researchers working with data from ESA’s Integral gamma-ray observatory has disproved theories that some form of dark matter explains mysterious radiation in the Milky Way.

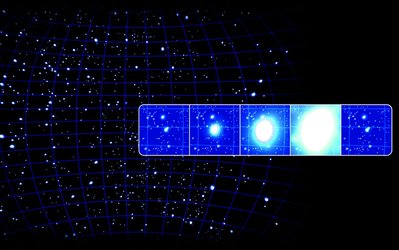

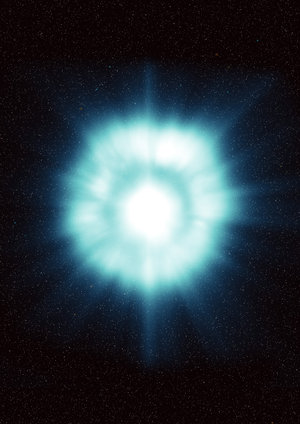

That this radiation exists has been known since the 1970s, and several theories have been proposed to explain it. Integral’s unprecedented spectral and spatial resolution showed that it strongly peaks towards the centre of the Galaxy, with an asymmetry along the Galactic disc.

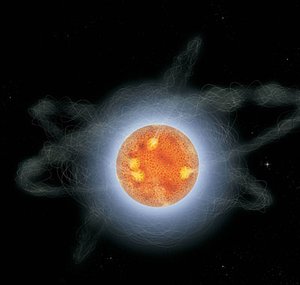

Several researchers have invoked a variety of dark matter to explain Integral’s observations. Dark matter is thought to exist throughout the Universe – undetectable matter that differs from the normal material that makes up stars, planets and us. It is also believed to be present within and around the Milky Way, in the form of a halo.

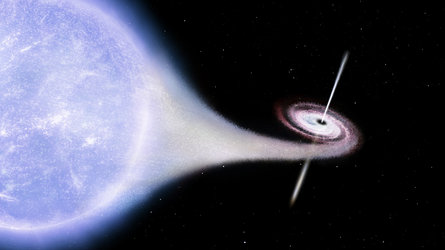

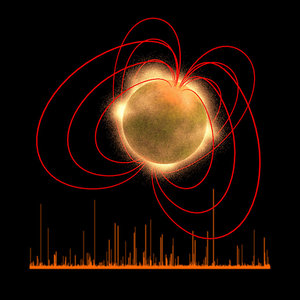

The recent study has found that the ‘positrons’ fuelling the radiation are not produced from dark matter but from an entirely different, and much less mysterious, source: massive stars explode and leave behind radioactive elements that decay into lighter particles, including positrons, the antimatter counterparts of electrons.

The reasoning behind the original hypothesis was that positrons, being electrically charged, would be affected by magnetic fields and thus would not be able to travel far. As the radiation was observed in places that did not match the known distribution of stars, dark matter was invoked as an alternative for the origin of the positrons.

But the recent finding by a team of astronomers led by Richard Lingenfelter at the University of California at San Diego, proves otherwise. The astronomers show that the positrons formed by radioactive decay of elements left behind after explosions of massive stars are, in fact, able to travel great distances, with many leaving the thin Galactic disc.

Taking this into account, dark matter is no longer required to explain what Integral saw. A better understanding of how positrons behave has explained the mysterious radiation in our Galaxy.

Read this story in detail on the ESA Science and Technology pages .

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland