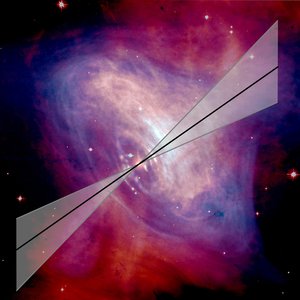

Radioactive decay of titanium powers supernova remnant

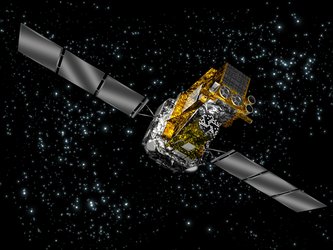

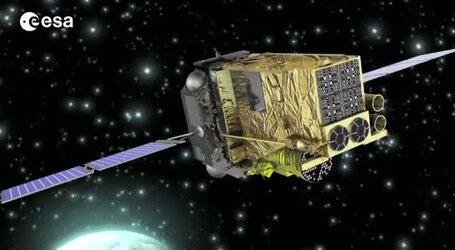

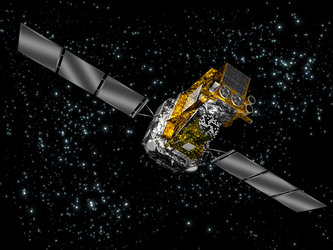

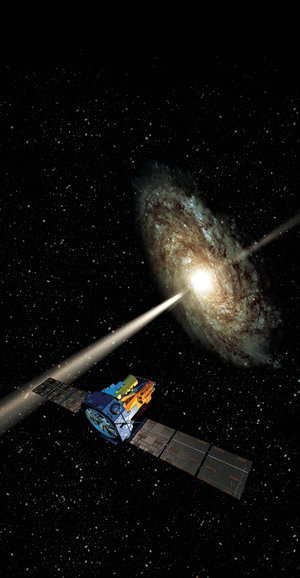

The first direct detection of radioactive titanium associated with supernova remnant 1987A has been made by ESA’s Integral space observatory. The radioactive decay has likely been powering the glowing remnant around the exploded star for the last 20 years.

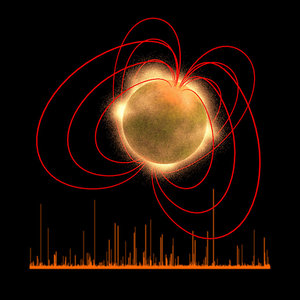

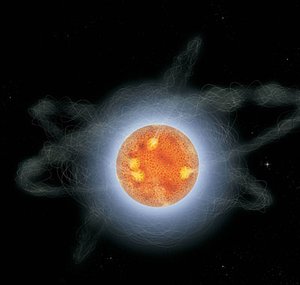

Stars are like nuclear furnaces, continuously fusing hydrogen into helium in their cores. When stars greater than eight times the mass of our Sun exhaust their hydrogen fuel, the star collapses. This may generate temperatures high enough to create much heavier elements by fusion, such as titanium, iron, cobalt and nickel.

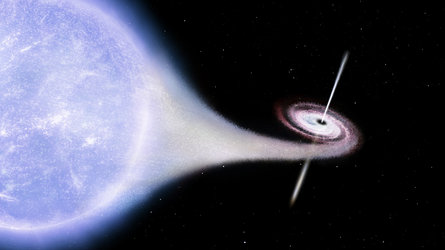

After the collapse, the star rebounds and a spectacular supernova explosion results, with these constituent elements flung into space.

Supernovae can shine as brightly as entire galaxies for a very brief time thanks to the enormous amount of energy released in the explosion.

After the initial flash has faded, the total luminosity of the remnant is provided by the release of energy from the natural decay of radioactive elements produced in the explosion.

Each element emits energy at some characteristic wavelengths as it decays, providing insight into the chemical composition of the supernova ejecta – the shells of material flung out by the exploding star.

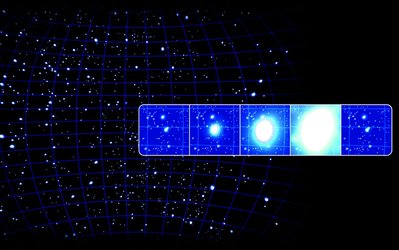

Supernova 1987A, located in one of the Milky Way’s nearby satellite galaxies, the Large Magellanic Cloud, was close enough to be seen by the naked eye when its light first reached Earth in February 1987.

During the peak of the explosion, fingerprints of elements from oxygen to calcium were detected, representing the outer layers of the ejecta.

Soon after, signatures of the material synthesised in the inner layers could be seen in the radioactive decay of nickel-56 to cobalt-56, and its subsequent decay to iron-56.

Now, thanks to more than 1000 hours of observation by Integral, high-energy X-rays from radioactive titanium-44 in supernova remnant 1987A have been detected for the first time.

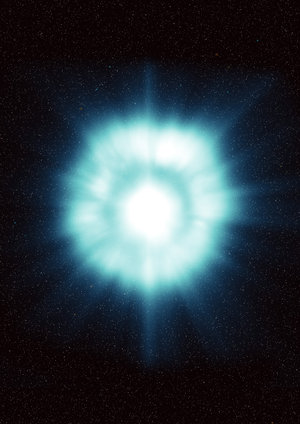

“This is the first firm evidence of titanium-44 production in supernova 1987A and in an amount sufficient to have powered the remnant over the last 20 years,” says Sergei Grebenev from the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Science in Moscow, and the first author of the paper reporting the results in Nature.

From their analysis of the data, the astronomers estimated that the total mass of titanium-44 that must have been produced just after the core collapse of SN1987A’s progenitor star amounted to 0.03% of the mass of our own Sun.

This value is near the upper boundary of theoretical predictions and is nearly twice the amount seen in supernova remnant Cas A, the only other remnant where titanium-44 has been detected.

“The high values of titanium-44 measured in Cas A and SNR1987A are likely produced in exceptional cases, favouring supernovae with an asymmetric geometry, and perhaps at the expense of the synthesis of heavier elements,” says Dr Grebenev.

“This is a unique scientific result obtained by Integral that represents a new constraint to be taken into account in future simulations for supernova explosions,” adds Chris Winkler, ESA’s Integral project scientist and co-author of the Nature paper.

“These observations are broadening our understanding of the processes involved during final stages of a massive star’s life.”

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland