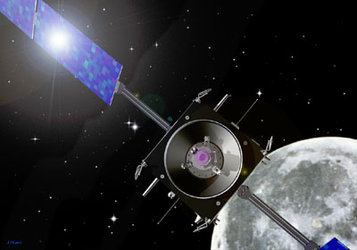

Europe rediscovers the Moon with SMART-1

ESA PR 30-2006. Now Europe too can say it has been to the Moon. In the early morning of 3 September this year (at 07:41 Central European Summer Time, as currently estimated), the European Space Agency’s SMART-1 mission will end its exploration adventure through a small impact on the lunar surface.

The whole story began in September 2003, when an Ariane 5 launcher blasted off from Kourou, French Guiana, to deliver the European Space Agency’s lunar spacecraft SMART-1 into Earth orbit. SMART-1 is a small unmanned satellite weighing 366 kilograms and roughly fitting into a cube just 1 metre across, excluding its 14-metre solar panels (which were folded during launch).

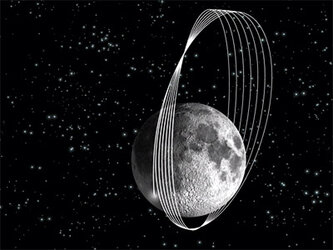

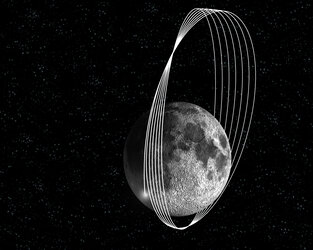

After launch and injection into an elliptical orbit around the Earth, the gentle but steady push provided by the spacecraft’s highly innovative electric propulsion engine forcefully expelling xenon gas ions caused SMART-1 to spiral around the Earth, increasing its distance from our planet until, after a long journey of about 14 months, it was “captured” by the Moon’s gravity.

To cover the 385,000 km distance that separates the Earth from the Moon if one travelled in a straight line, this remarkably efficient engine brought the spacecraft on a 100 million km long spiralling journey on only 60 litres of fuel! The spacecraft was captured by the Moon in November 2004 and started its scientific mission in March 2005 in an elliptical orbit around its poles. ESA’s SMART-1 is currently the only spacecraft around the Moon, paving the way for the fleet of international lunar orbiters that will be launched from 2007 onwards.

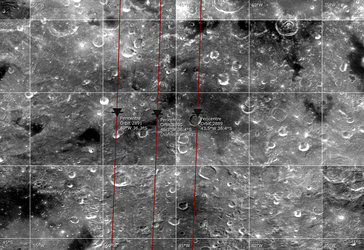

The story is now close to ending. On the night of Saturday 2 to Sunday 3 September, looking at the Moon with a powerful telescope, one may be able to see something special happening. Like most of its lunar predecessors, SMART-1 will end its journey and exploration of the Moon by landing in a relatively abrupt way. It will impact the lunar surface in an area called the “Lake of Excellence”, situated in the mid-southern region of the Moon’s visible disc at 07:41 CEST (05:41 UTC), or five hours before if it finds an unknown peak on the way.

The story is close to ending

After 16 months harvesting scientific results in an elliptical orbit around the Moon’s poles (at distances of between 300 and 3.000 km), the mission is almost over. The spacecraft perilune has now dropped below an altitude of 300 km from the lunar surface and will get a closer look at specific targets on the Moon before landing in a controlled manner on the moon surface (controlled, that is, in terms of where and when). It will then 'die' there.

“With a relative low speed at impact (2 km/sec or 7200 km/h), SMART-1 will create a small crater of 3 to 10m in diameter’s” says Bernard Foing, SMART-1 Project scientist, “a crater no larger than that created by a 1kg meteorite on a surface already heavily affected by natural impacts”.

Mission controllers at the European Space Agency’s Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt, near Frankfurt, Germany will monitor the final moments before impact step by step.

Final milestones of SMART-1 flight operations

In June, SMART-1 mission controllers at ESOC completed a series of complex thruster firings aimed at optimising the time and location of the spacecraft’s impact on the Moon's surface. They had to be done with the thrusters of the attitude control system since all the Xenon of the Ion engine had been consumed in 2005.

The manoeuvres have shifted the time and location of impact, which would otherwise occurred in mid-August on the far side of the Moon; impact is now set to occur on the near side and current best estimates show the impact time to be around 07:41 CEST (05:41 UTC) on Sunday 3 September.

"Mission controllers and flight dynamics engineers have analysed the results of the manoeuvre campaign to confirm and refine this estimate," says Octavio Camino-Ramos, SMART-1 spacecraft operations manager at ESA/ESOC. "The final adjustment manoeuvres are planned for 25th of August, which may still have a consequence on the final impact time", he added.

Large ground telescopes will be involved before and during impact to make observations of the event, with several objectives:

- To study the physics of the impact (ejected material, mass, dynamics and energy involved).

- To analyse the chemistry of the surface by collecting the specific radiation emitted by the ejected material (‘spectra’)

- To help technological assessment: understand what happens to the impacting spacecraft to know better how to prepare for future impactor experiments (for instance on satellites to intercept meteorites menacing our planet)

Media briefing on 3 September, major press conference on 4 September

Media representatives wishing to witness the impact event at ESOC and share the excitement of it with specialists and scientists available for interviews as of early morning on Sunday 3 September, or wishing to attend the press conference on Monday 4 September to highlight the first results of the impact, are required to fill in the attached registration form and return it by fax to the ESOC Communication Office by Thursday 31 August.

Note for Editors

Why so SMART?

SMART-1 is packed with high-tech devices and state-of-the-art scientific instruments. Its ion engine, for instance, works by expelling a continuous beam of charged particles, or ions, which produces a thrust that drives the spacecraft forward. The energy to power the engine comes from the solar panels, hence the term 'solar electric propulsion'. The engine generates a very gentle continuous thrust which causes the spacecraft to move relatively slowly: SMART-1 accelerates at just 0.2 millimetres per square second, a thrust equivalent to the weight of a postcard.

By necessity, SMART-1’s journey to the Moon has been neither quick nor direct. This was because, for the first time, ESA wanted to test electric propulsion on a trip similar to an interplanetary journey. After launch, SMART-1 went into an elliptical orbit around the Earth. Then the spacecraft fired its ion engine, gradually expanding its elliptical orbit and spiralling out in the direction of the Moon’s orbital plane.

Month after month this brought SMART-1 closer to the Moon. This spiralling journey accounted for more than 100 million kilometres, while the Moon – if you wanted to go there in a straight line - is only between 350,000 and 400,000 kilometres away from the Earth.

As SMART-1 neared its destination, it began using the gravity of the Moon to bring it into a position where it was captured by the Moon’s gravitational field. This occurred in November 2004. After being captured by the Moon, in January 2005, SMART-1 started to spiral down to its final operational polar elliptical orbit with a perilune (closest point to the lunar surface) altitude of 300 km and apolune (farthest point) altitude of 3000 km to conduct its scientific exploration mission.

What was there to know that we didn’t know already?

Despite the number of spacecraft that have visited the Moon, many scientific questions concerning our natural satellite remained unanswered, notably to do with the origin and evolution of the Moon, and the processes that shape rocky planetary bodies (such as tectonics, volcanism, impacts and erosion).

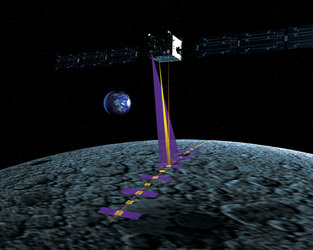

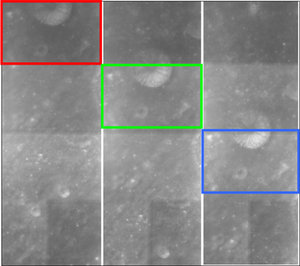

Thanks to SMART-1, scientists all over Europe and around the world now have the best resolution surface images ever from lunar orbit, as well as a better knowledge of the Moon’s minerals. For the first time from orbit, they have detected calcium and magnesium using an X-ray instrument. They have measured compositional changes from the central peaks of craters, volcanic plains and giant impact basins. SMART-1 has also studied impact craters, volcanic features and lava tubes, and monitored the polar regions. In addition, it found an area near the north pole where the Sun always shines, even in winter.

SMART-1 has roamed over the lunar poles, enabling it to map the whole Moon, including its lesser known far side. The poles are particularly interesting to scientists because they are relatively unexplored. Moreover, some features in the polar regions have a geological history which is distinct from the more closely studied equatorial regions where all previous lunar landers have touched down so far.

With SMART-1, Europe has played an active role in the international lunar exploration programme of the future and, with the data thus gathered, is able to make a substantial contribution to that effort. SMART-1 experience and data are also assisting in preparations for future lunar missions, such as India’s Chandrayaan-1, which will reuse SMART-1’s infrared and X-ray spectrometers.

SMART-1 is equipped with completely new instruments, never used close to the Moon before. These include a miniature camera, and X-ray and infrared spectrometers, which are all helping to observe and study the Moon.

Its solar panels use advanced gallium-arsenide solar cells, chosen in preference to traditional silicon cells. One of the experimental instruments onboard SMART-1 is OBAN, which has been testing a new navigation system that will allow future spacecraft to navigate on their own, without the need for control from the ground.

Instruments and techniques tested in examining the Moon from SMART-1 will later help ESA's BepiColombo spacecraft to investigate the planet Mercury.

For further information:

ESA Media Relations Office

Phone: + 33 1 5369 7155

Fax: + 33 1 5369 7296

Queries: media@esa.int

Further information on the event at ESOC

Jocelyne Landeau-Constantin

Head of Corporate Communication Office ESA/ESOC

Darmstadt, Germany : Tel. + 49 6151 90 26 96 / email: jlc@esa.int

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland