Exploring an asteroid with the Desert RATS

Earlier this month, European scientists linked up with astronauts roaming over the surface of an asteroid. Desert RATS, NASA’s realistic simulation of a future mission, this year included a European dimension for the first time.

It was not really an asteroid, but a desert near Flagstaff in Arizona, USA. Since 1999, scientists, astronauts and engineers from various NASA establishments and universities have gathered once a year to simulate human missions to the Moon and Mars.

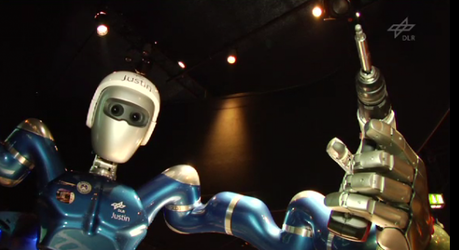

Desert RATS – Desert Research and Technology Studies – have tested rovers, habitats, spacesuits, instruments, robots, communication systems, research methods and other technical, scientific and operational aspects of future missions.

These realistic ‘missions’ in extreme environments help to guide planning for future space exploration and build valuable experience in complex operations.

Fly me to an asteroid

This time, the crew of astronauts and geologists ‘landed’ on a nearby asteroid and ventured out on field trips – by foot and on two Space Exploration Vehicles.

For two weeks, the crew lived in a Deep Space Habitat with realistic radio links to their mother craft and mission control on Earth.

They had to cope with a two-way communications delay of 100 seconds with Earth, and limited bandwidth.

Reproducing the low gravity on an asteroid was impossible, but the ‘spacewalkers’ acted as though they were on a small body.

For instance, they had to attach themselves to the ground when they used their hammers to take geological samples – otherwise, the recoil would have sent them spinning into space.

Europe comes aboard

In last year’s DRATS, William Carey, an ESA specialist in future exploration operations strategies, was the only European in Arizona but this year a full science team was active in Europe.

“The simulation is similar to a cricket game: long periods of inactivity punctuated by periods of intense concentration,” explained William, referring to the long preparations.

“When the extravehicular activities began, everyone’s hearts started to beat faster.”

This was especially so in the two ‘science backrooms’, each with a team of scientists and engineers supporting one vehicle and its crew. The European scientists worked in the Erasmus backroom at ESA’s ESTEC technical centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands which normally support science operations for the ISS.

The team of 11 from Italy, France, the Netherlands, ESA and NASA communicated with the crews out in Arizona, just like a backroom would on a real asteroid mission.

“These scientists were the backup eyes and the extra brain power of the crew,” said Sylvie Espinasse, coordinator for the undertaking in ESA.

“Operating with access to real-time audio and video feeds, we could monitor astronauts and geologists in the field and communicate with them taking into account the delay.”

During the two intense days when ESTEC was online, the team tracked everything on the asteroid surface, observing what the crew was doing, trying to make geological sense of it and helping the explorers to squeeze all they could from the limited spacewalking time.

“I enjoyed this different type of exploration tremendously,” said Goro Komatsu, a field geologist from the International Research School of Planetary Science, Italy.

He was excited when the action was interrupted during the second day by a thunderstorm: “It was very useful to learn how to face the unexpected!”

After all, on a real mission to an asteroid, there might be solar storms, hampering communications and forcing the astronauts to protect themselves.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland