Space station tracks months-long voyages of ships at sea

ESA’s experimental ship detector on the International Space Station has pinpointed more than 60 000 ocean-going vessels so far. It has been able to follow the routes of individual ships for months at a time.

Hosted by Europe’s Columbus research module on the International Space Station (ISS), and activated on 1 June, the tracking system picks up Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals, more usually employed by port authorities and coastguards to keep tabs on local ship traffic.

All international vessels, passenger carriers and cargo ships above 300 tonnes are mandated to carry AIS VHF-radio transponders.

“AIS messages are designed to be used only on a local basis, with a range of 50 km or so to the horizon,” explained Torkild Eriksen of the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI), which built the NORAIS receiver in collaboration with Kongsberg Seatex.

“Instead, we are picking them up from 350 km in orbit, when they might have travelled up to 2000 km. Our receiver, therefore, had to be designed for extreme sensitivity to detect such weak signals.”

This initiative, funded by ESA, is part of the trend of using the ISS as a platform to observe and monitor our planet. The Station’s orbital inclination and altitude are different to those of most observation satellites, offering other ground patterns over about 95% of the population.

“Operating from space, we have been able to track ships for long periods as they cross the ocean,” explained Andreas-Nordomo Skauen of FFI. Nearly 30 million AIS messages were received in only four months from more than 60 000 different transmitters.

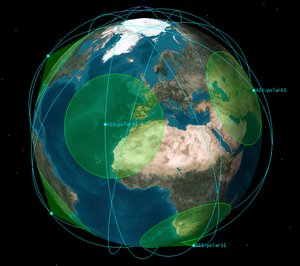

The results give an overview of the ship traffic beneath the Station’s orbit, with coverage extending as far as polar latitudes.

A wide field of view

“Over the four-month period,” added Mr Skauen, “we watched one ship travel from the western Pacific to Argentina then over to Europe and down to Africa, picking up its AIS signal from two to seven times per day, depending on latitude.

“So we can reveal exactly where a vessel has been in the marine environment, information that would be very useful to port, fisheries and marine authorities.”

From the Station’s orbit, the NORAIS receiver has a maximum 4400 km-diameter field of view. Signal detection is easiest when vessels are far apart in open water. In the busiest stretches of water such as the English Channel, North Sea and Malacca Straits, AIS signals swamp each other, and vessels get lost in the crowd.

“This is not a problem, however, as these particular areas are already well covered by coastal base stations,” explained Mr Eriksen. “This system’s usefulness is its global reach.”

The Vessel ID System on Columbus has run on a largely automated basis with weekly instructions uploaded via Norway’s national User Support Operations Centre, part of an ESA-wide network serving ISS experimenters.

“We surveyed both land and ocean, and will pass our findings to the International Telecommunications Union and International Maritime Organisation as they consider introducing these new bands,” said Mr Eriksen.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland