Possible origin of Saturn's mysterious G ring

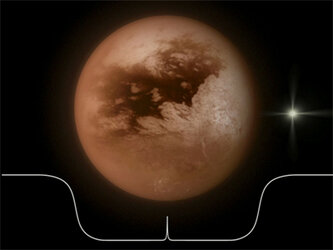

With data from the Cassini spacecraft, an international team of scientists may have identified the source of one of Saturn's more mysterious rings. The enigmatic G ring is likely produced by relatively large, icy particles that reside within a bright arc on the ring's inner edge.

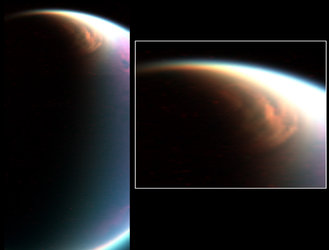

The particles are confined within the arc by gravitational effects from Saturn's moon Mimas. Micrometeoroids, tiny meteoroids or particles of dust that pervade space, collide with the icy particles, releasing smaller, dust-sized particles that brighten the arc. Plasma, an extremely variable gas made up of charged particles but electrically neutral, pervades the giant planet's magnetic field. It sweeps through this arc continuously, dragging out the fine particles, which create the G ring.

The finding is evidence of the complex interaction between Saturn's moons, rings and magnetosphere. Studying this interaction is one of Cassini's objectives.

"Distant pictures from the cameras tell us where the arc is and how it moves, while plasma and dust measurements taken near the G ring tell us how much material is there," said Matthew Hedman, a Cassini imaging team associate at Cornell University, in the United States, and lead author of the paper that describes these results.

Saturn's rings are an enormous, complex structure, and their origin is a mystery. The rings are labelled in the order they were discovered. From the planet outward, they are D, C, B, A, F, G and E. The main rings - A, B and C from edge-to-edge, would fit neatly in the distance between Earth and the Moon. The most transparent rings are D - interior to C - and F, E and G, outside the main rings.

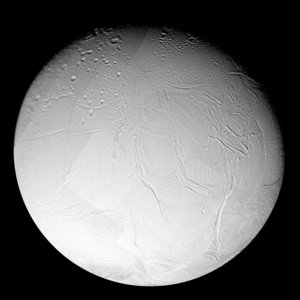

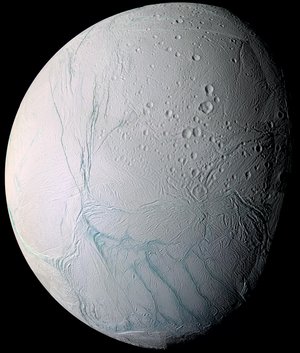

Unlike Saturn's other dusty rings, such as the E and F rings, the G ring is not associated closely with moons that could either supply material directly to it - as its moon Enceladus does for the E ring - or sculpt and perturb its ring particles, as Prometheus and Pandora do for the F ring. The location of the G ring continued to defy explanation, until now.

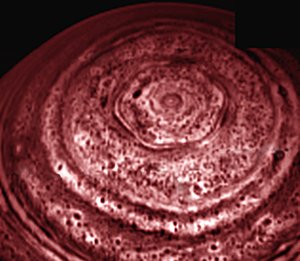

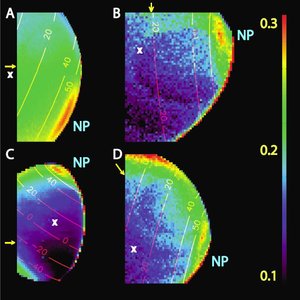

Cassini images show that the bright arc within the G ring extends one-sixth of the way around Saturn and is about 250 km wide, much narrower than the full 5955-km width of the G ring. The arc has been observed several times since Cassini's arrival at the ringed planet in 2004 and thus appears to be a long-lived feature. A gravitational disturbance caused by the moon Mimas exists near the arc.

As part of their study, Hedman and colleagues conducted computer simulations which show that the gravitational disturbance of Mimas could indeed produce such a structure in Saturn's G ring. The only other places in the Solar System where such disturbances are known to exist are in the ring arcs of Neptune.

Cassini's magnetospheric imaging instrument detected depletions in charged particles near the arc in 2005. According to scientists, unseen mass in the arc must be absorbing the particles. "The small dust grains that the Cassini camera sees are not enough to absorb energetic electrons," said Elias Roussos of the Max-Planck-Institute for Solar System Research, Germany, and member of the magnetospheric imaging team. "This tells us that a lot more mass is distributed within the arc."

The researchers concluded that there is a population of larger, as-yet-unseen bodies hiding in the arc, ranging in size from that of peas to small boulders. The total mass of all these bodies is equivalent to that of an ice-rich, small moon that's about 100 metres wide.

Joe Burns, a co-author of the paper from Cornell University and a member of the imaging team, said, "We'll have a super opportunity to spot the G ring's source bodies when Cassini flies about 966 km from the arc 18 months from now."

Notes for editors:

The findings appear in ’The Source of Saturn's G Ring’ by Hedman M., Burns J., Tiscareno, M., Porco, C., Jones, G., Roussos, E., Krupp, N., Paranicas, C., and Kempf, S. in the 2 August issue of the journal Science. The paper is based on observations made by multiple Cassini instruments in 2004 and 2005.

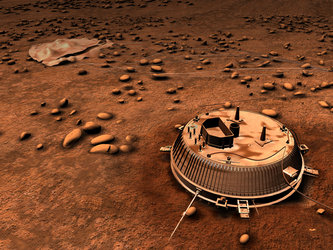

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Cassini-Huygens mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington DC. JPL designed and assembled the Cassini orbiter. Development of the Huygens Titan probe was managed by ESA’s European Space Technology and Research Centre (ESTEC). ASI managed the realisation of the high-gain antenna and the other instruments of its participation. The imaging team is based at the Space Science Institute, USA. The magnetospheric imaging instrument team is based at Johns Hopkins University, USA.

For more information:

Jean-Pierre Lebreton, ESA Huygens Project Scientist

Email: jean-pierre.lebreton @ esa.int

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland