Herschel detects abundant water in planet-forming disc

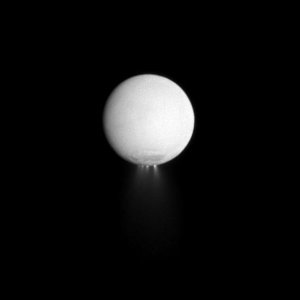

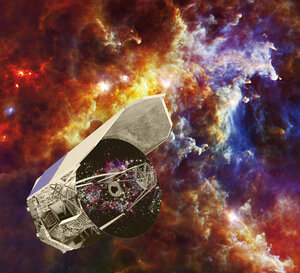

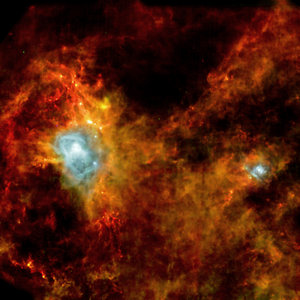

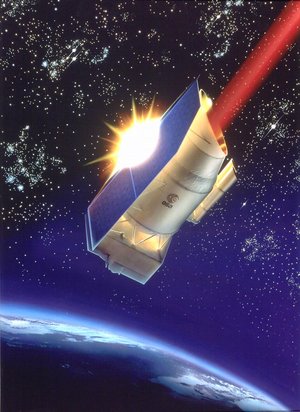

ESA’s Herschel space observatory has found evidence of water vapour emanating from ice on dust grains in the disc around a young star, revealing a hidden ice reservoir the size of thousands of oceans.

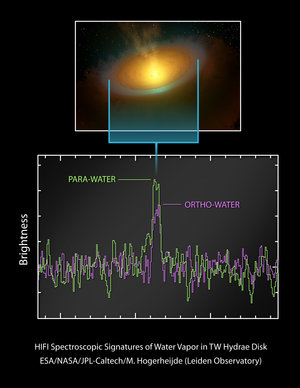

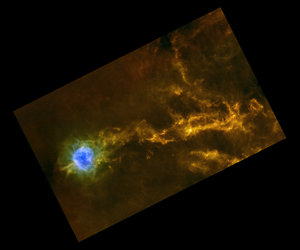

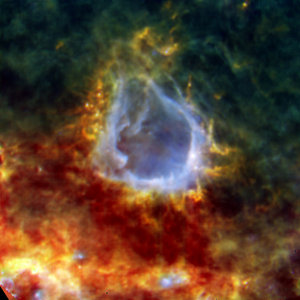

TW Hydrae, a star between 5-10 million years old, and only 176 light-years away, is in the final stage of formation, and is surrounded by a disc of dust and gas that may condense to form a complete set of planets.

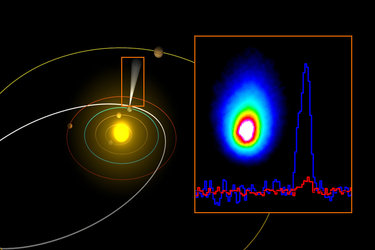

It is believed that a large proportion of Earth’s water may have come from ice-laden comets that bombarded our world during and after its formation. Recent studies of comet 103P/Hartley 2 with Herschel shed new light on how water may have come to Earth, with its findings of the first Earth-like water in a comet. Until now, however, almost nothing was known about reservoirs in planet-forming discs around other stars.

This new detection is the first of its kind and has been made possible by Herschel’s HIFI instrument.

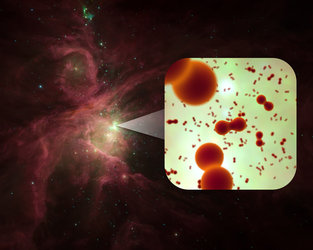

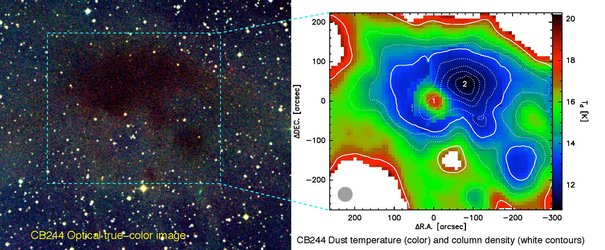

The tell-tale water vapour signature, believed to be produced when the ice coated dust grains are warmed by interstellar UV radiation, has been detected throughout the disc around TW Hydrae, and, though weaker than expected, it hints at a substantial reservoir of ice. This could be a rich source of water for any planets that form around this young star.

"The detection of water sticking to dust grains throughout the disc would be similar to events in our own Solar System's evolution, where over millions of years, similar dust grains then coalesced to form comets," says Michiel Hogerheijde of Leiden University in the Netherlands, who led the study.

"These comets we believe became a contributing source of water for the planets."

The scientists ran detailed simulations, combining the new data with previous ground-based observations and some from NASA’s Spitzer telescope. From this they calculated the size of the ice reservoirs in the planet-forming regions.

Their results show that the total amount of water in the disc around TW Hydrae would fill several thousand Earth oceans.

"We already have approved time on Herschel to study more planet-forming regions around three other stars," says Dr Hogerheijde.

"We believe that will show similar results in terms of the water detections, but as our next observations will be of objects up to three times further in distance away, we'll need many more hours of observation time."

This research breaks new ground in understanding water’s role in planet-forming discs and gives scientists a new testing ground for looking at how water came to our own planet.

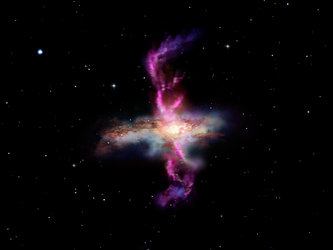

"With Herschel we can follow the trail of water through all the steps of star and planet formation," comments Göran Pilbratt, Herschel Project Scientist at ESA.

"Here we are studying the 'raw material' for planet formation, which is fundamental to an understanding of how planetary systems such as our own Solar System once formed."

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland