Titan’s tides point to hidden ocean

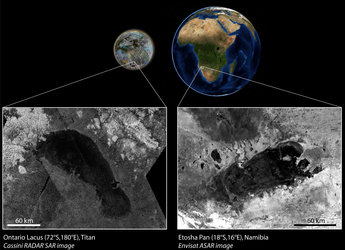

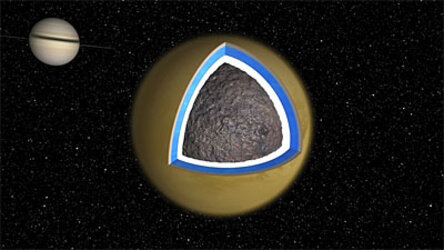

Nothing like it has been seen before beyond our own planet: large tides have been found on Saturn’s moon Titan that point to a liquid ocean – most likely water – swirling around below the surface.

On Earth, we are familiar with the combined gravitational effects of the Moon and Sun creating the twice-daily tidal rise and fall of our oceans. Less obvious are the tides of a few tens of centimetres in our planet’s crust and underlying mantle, which floats on a liquid core.

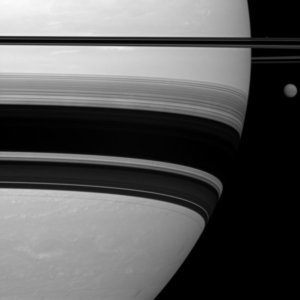

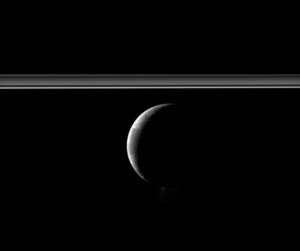

But now the international Cassini mission to Saturn has found that Titan experiences large tides in its surface.

“The important implication of the large tides is that there is a highly deformable layer inside Titan, very likely water, able to distort Titan’s surface by more than 10 metres,” says Luciano Iess of the Università La Sapienza in Rome, lead of author of the paper published in Science magazine.

If the moon were rigid all the way through, then tides of only one metre would be expected.

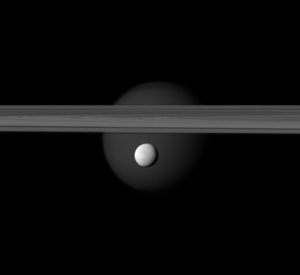

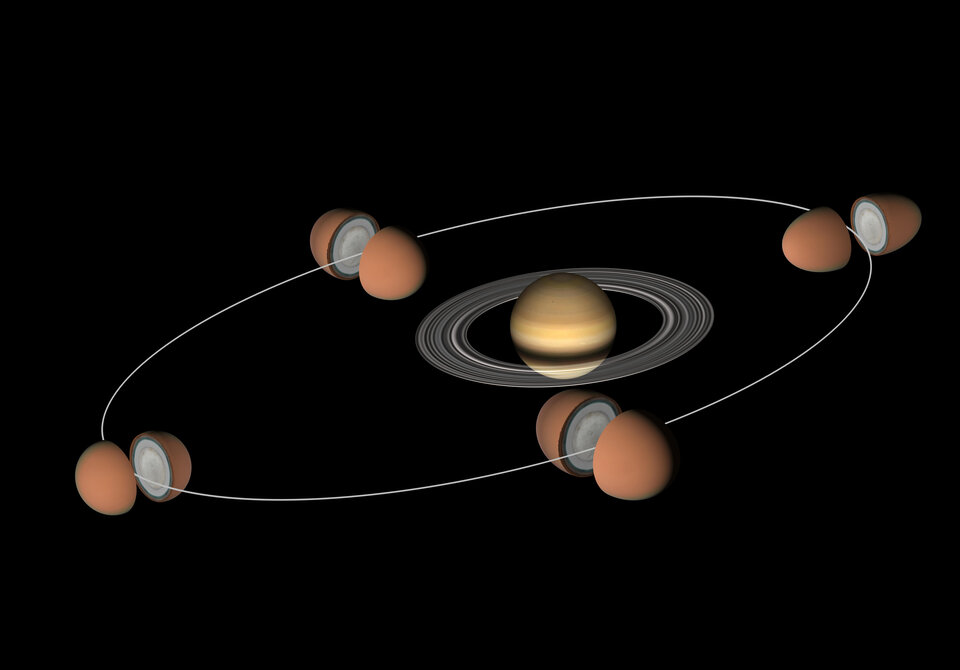

The tides were discovered by carefully tracking Cassini’s path as the probe made six close flybys of Saturn’s largest moon between 2006 and 2011.

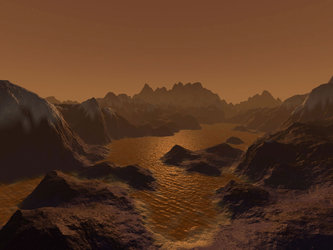

Titan orbits Saturn in an elliptical path once every 16 days, changing shape with the varying pull of its parent’s gravity – at its closest point, it is stretched into a rugby-ball shape.

Titan’s gravity pulls on Cassini and the moon’s changing shape affects its trajectory slightly differently on each visit, revealed by tiny differences in the frequency of radio signals received from the spacecraft back at Earth.

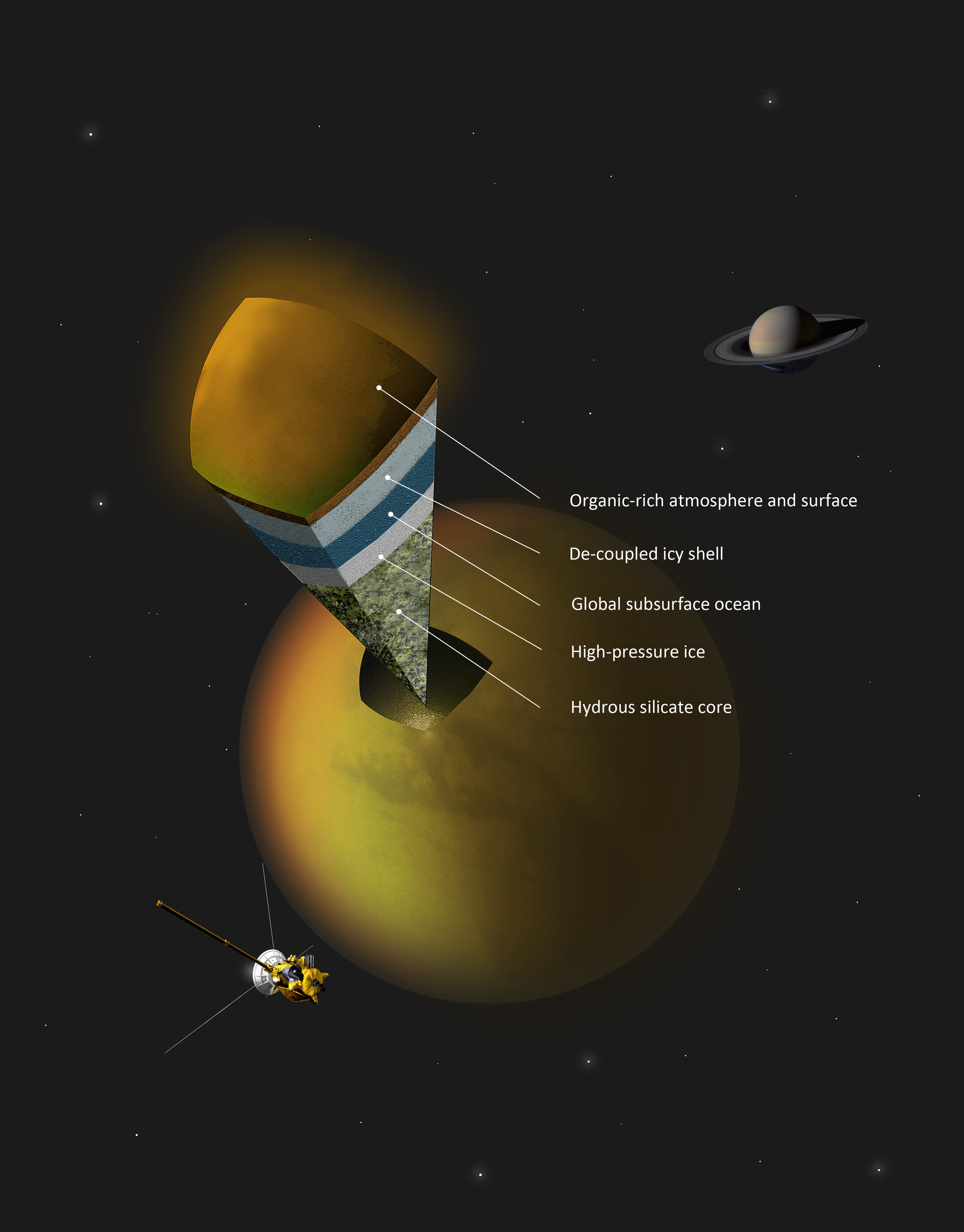

“We know from other Cassini instruments that the surface of Titan is made of water ice mostly covered with a layer of organic molecules – the water ocean may also be doped with other ingredients, including ammonia or ammonium sulphate,” underlines Dr Iess.

“Although our measurements do not tell anything about the depth of the ocean, models suggest that it may be up to 250 km deep beneath an ice shell some 50 km thick.”

This also goes some way to explaining the puzzle of why Titan has so much methane in its atmosphere, which given its naturally short lifetime must be replenished somehow.

“We know that the reservoirs of methane in Titan’s surface hydrocarbon lakes are not enough to explain the large quantities in the atmosphere, but an ocean could act as a deep reservoir,” explains Dr Iess.

“This is the first time Cassini has shown the presence of an ocean below Titan’s surface, providing an important clue as to how Titan ‘works’, while also pointing to another place in the Solar System where liquid water is abundant,” says Nicolas Altobelli, ESA’s Cassini project scientist.

Notes for editors

“The Tides of Titan” by L. Iess et al. is published in Science, 28 June 2012.

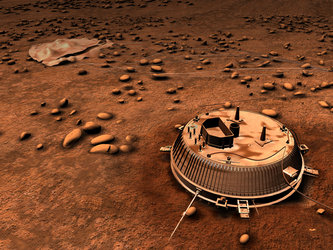

The Cassini–Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C.

For further information please contact:

ESA Media Relations

media@esa.int

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland