Once in a lifetime: the Venus transit 2004

On 8 June 2004, you will be able to witness an astronomical event no living person has seen, a transit of Venus.

This happens when the planet moves directly between the Earth and the Sun. This will only be the sixth such event since the invention of the telescope - the most recent occurred in 1882.

The next Venus transit will take place in June 2012 but on this occasion it will already be in progress before the Sun rises in Europe. No one living today will see the one after that, as it will not take place until 2117.

Weather permitting, half of the Earth will have a view of the tiny black dot of Venus moving across the disk of the Sun (REMEMBER never to look at the Sun with unprotected eyes or through a telescope).

Past transits of Venus have enabled us to discover a lot about our Solar System and the Universe. In 1716 Edmund Halley proposed that the 1761 transit of Venus should test the concept of measuring distance using 'parallax'.

By observing the apparent shift in position of Venus against the background of the Sun as seen from two different places on Earth, observers could use trigonometry to calculate the distance from Earth to Venus.

Kepler's Third Law of Planetary Motion allowed the distances of the planets from the Sun to be calculated from measurements of their orbital periods. By knowing the distance to Venus we could calculate the distance from Earth to the Sun. In each successive transit, scientists have made better calculations of this distance.

Once the distance to the Sun was known, the distances to all of the other planets could be easily derived from our knowledge of celestial mechanics (the way things move in space) and from this, the size of the Solar System. ESA's Hipparcos mission has also measured the distance to 120 000 stars using this technique.

A transit of Venus causes a tiny reduction in light from the Sun. Knowing this, by careful observations from space starting with the COROT mission in 2006, scientists will search for Earth-like planets around distant stars by using highly sensitive instruments to observe tiny decreases in measured brightness.

Mysterious Venus

Much of our knowledge of Venus itself has come from just five observations of the transit of the planet. During the 1761 transit, Lomonosov used a telescope to observe that Venus had an atmosphere.

But although Venus is very similar to Earth in size and mass, it has evolved in a radically different manner, with a surface temperature hotter than a kitchen oven and a choking mixture of noxious gases for an atmosphere. Hurricane force winds permanently encircle the planet, and it has a very weak magnetic field.

In the past, both the Russians and Americans have sent spacecraft to Venus. As the closest planet to the Earth, it was a natural target. These studies revealed details about the surface of the planet but Venus has been out of the limelight during the last decade, despite several scientific puzzles remaining.

For example, what are the characteristics of the atmosphere? How does it circulate? How does the composition of the atmosphere change with depth? How does the atmosphere interact with the surface? How does the upper atmosphere interact with the solar wind? Why Venus rotates backwards and so slowly?

Enter Venus Express...

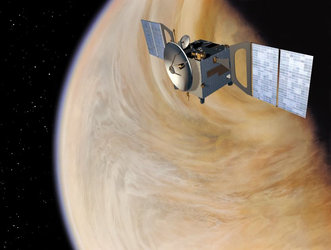

ESA is launching a mission next year to find out more about our enigmatic neighbour - Venus Express will be launched in November 2005. From idea in 2001 to launch, the Venus Express mission is one of the fastest ever to be developed.

The spacecraft is being built to the same design as Mars Express, using instruments originally built as flight spares for Mars Express and Rosetta, as well as two newly built instruments.

Venus Express will be the first spacecraft to perform a global investigation of the Venusian atmosphere and of the plasma environment, in an attempt to answer many of these still puzzling questions.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland