The science of solar eclipses

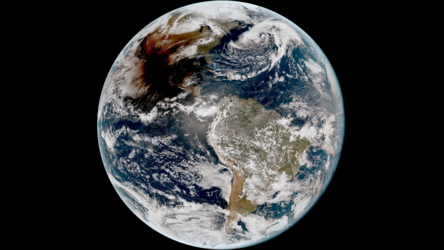

Eclipses have captivated humanity for thousands of years. They inspired early astronomers to map the skies and sparked discoveries that continue to shape science today. During a solar eclipse, the Moon passes directly between Earth and the Sun, blocking its light either partially or entirely. These moments turn eclipses into a natural laboratory, revealing details about the Sun’s outer layers, the Moon’s surface,and the Universe itself.

Past lessons from solar eclipses

More than just a source of legend, myth and superstition, eclipses have led to groundbreaking scientific discoveries.

For millennia, people have tried to predict when the next eclipse would appear. Ancient astronomers tracked the movement of the Sun, Moon and stars beyond, doing their best to decipher how they move with respect to one another. Thanks to solar eclipses, the fact that the Moon is closer to Earth than the Sun has been known since prehistoric times.

In 1715, Edmund Halley was the first to record what would later be called ‘Baily’s beads’ and the ‘diamond ring effect’. When just a sliver of sunlight passes the Moon’s edge during a solar eclipse, the Moon’s mountainous and cratered surface lets beads of light shine through some regions but not others. This is how solar eclipses reveal the Moon’s rugged topography.

More recently, a similar effort changed our understanding of the Universe forever. During the famous total solar eclipse in 1919, astronomer Arthur Eddington confirmed Einstein’s theory of general relativity by observing that the Sun’s gravity bent starlight passing close to it. This proved that gravity is not just a force between massive objects – it affects light, space and time itself.

Eclipses reveal the Sun’s corona

Solar eclipses give us a unique chance to observe parts of the Sun that are usually hidden by intense light. During a total eclipse, the Moon completely blocks out the Sun’s bright surface and unveils the corona, the outermost part of its atmosphere. (During partial and annular solar eclipses, the Moon doesn’t cover the Sun in its entirety, and the corona can’t be seen as clearly.)

One mystery that continues to puzzle researchers is why the corona is so hot. While the Sun’s surface temperature is around 4500–6000 °C, the Sun’s corona reaches temperatures higher than a million degrees Celsius.

The corona is also key to our understanding of space weather produced by the Sun. This includes the ever-present but changeable solar wind and stormy outbursts such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections. Space weather can disrupt satellites, power grids, and communication systems on Earth.

By observing the corona during totality, scientists can see how material moves outward from the Sun’s surface into space. Eclipses, therefore, provide a vital glimpse into processes that directly affect our planet.

Other ways to see the corona

Total solar eclipses provide rare moments to study the Sun’s corona in its entirety, from the Sun’s surface to its outer reaches. It is a stroke of celestial luck that the Moon’s size and distance from Earth make it just right to match the size of the Sun in the sky.

Unfortunately, natural solar eclipses are short-lived and can only be seen from a small region on Earth’s surface. When a ground-based telescope lies in the path of a solar eclipse, we obtain beautifully detailed images of the Sun’s glowing corona. Otherwise, we rely on smaller telescopes and cameras that can be positioned along the ‘path of totality’ on Earth’s surface.

Many space missions, including the European Space Agency's SOHO and Solar Orbiter, observe the Sun’s corona by imitating a solar eclipse. They carry instruments called coronagraphs, consisting of a light detector (a camera) combined with an external disc to block out the Sun’s light. SOHO and Solar Orbiter's coronagraphs can see the corona down to around 350 000 km (around 0.5 times the radius of the Sun) from the Sun's surface.

Coronagraphs can never see as close to the Sun’s surface as we can during a natural solar eclipse. Like water waves spreading out behind an obstacle, light waves can bend or ‘diffract’ around the edge of the light-blocking disc, obscuring the faint glow of the Sun's corona. This effect gets stronger the closer the disc is to the detector. Normal coronagraphs can't put the light-blocking disc further than some tens of centimetres from the detector, so instead they reduce this effect by making the disc bigger than the size of the Sun as it appears to the camera.

ESA’s new Proba-3 mission will see more of the Sun’s inner corona than ever before by flying two separate spacecraft 150 m apart. Proba-3’s Occulter spacecraft fulfils the Moon’s role in a solar eclipse, blocking the Sun’s direct light for the Coronagraph spacecraft. The large distance between the two spacecraft reduces diffraction effects, allowing Proba-3’s coronagraph to see the corona down to just 70 000 km above the Sun’s surface. Its range of view will still be less than what we can see during a total solar eclipse, but Proba-3's artificial eclipse will last hours at a time, summing to 1000 hours over two years.

A different way to see the inner corona is to use a camera that can see ultraviolet and X-ray wavelengths sent out by the extremely hot, glowing charged gas (plasma) near the Sun’s surface. These wavelengths can only be seen from space because Earth’s atmosphere blocks them. Spacecraft like ESA’s Solar Orbiter and Proba-2 use this technique to capture beautiful images of the Sun year-round. However, these cameras struggle to see the fainter plasma farther out in the corona.

By comparing artificial solar eclipses created by space missions with ground-based data from natural eclipses, scientists can piece together a more complete picture of the Sun’s dynamic behaviour and its influence on Earth and beyond. The next time you witness a shadow crossing the sky, take a moment to reflect on the scientific marvels it reveals.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland