A giant step for Europe: An interview with Michael McKay

Michael McKay has the daunting task of being ultimately responsible for literally everything on Earth that Mars Express requires to get it to its final destination, and is also one of the people guiding the spacecraft there.

Michael McKay

ESOC Ground Segment Manager, and Flight Operations Director, Mars Express

Born: May 1956 in Belfast, Northern Ireland

BSc in Aeronautical Engineering from Queens University, Belfast, followed by an MSC in Computer Science.

Michael began his career at ESTEC in 1979 working in the field of cosmic ray physics and preparing the International Sun-Earth Explorer 3 mission. He became Spacecraft Operations Engineer for ESA's Exosat X-ray observatory satellite, a job that took him to ESOC for the first time in 1981.

He then worked as Deputy Spacecraft Operations Manager for the launch of ERS-1, becoming full Spacecraft Operations Manager for its successor, ERS-2, in 1995. He went on to serve as Ground Segment Manager for the trainee-operated Teamsat mission. In 1998 he was appointed Ground Segment Manager and Flight Operations Director for the SMART-1 and Mars Express missions.

He is married with three children. Besides his children, his hobbies include sailing, surfing and diving.

ESA: After five years of work, how do you feel as Mars Express finally nears its final destination?

Michael McKay

I'm feeling a great anticipation about exciting events ahead! All of this represents a new step forward for Europe. As Ground Segment Manager, I've been working on the mission ever since the design phase, responsible for everything on the ground you can think of needed for the mission to work, from software systems to ground stations.

Normally after launch the Ground Segment Manager hands over to the Flight Operations Director, but I've been lucky and I get to also get to be a Flight Operations Director for this mission, all the way to Mars!

Mars Express represents a faster way for ESA to work.

ESA: How does Mars Express differ from other missions you've worked on?

Michael McKay

Mars Express gets its name from two things: first that Mars is at its closest to us right now for almost 60,000 years – so the spacecraft has less distance to travel – but also because it represents a faster way for ESA to work.

In the past we might have started with a Mars fly-by mission, then followed up with an orbiter, then sent a lander. With Mars Express we're doing all those things at once. And we went from the design phase to flight in five years. That put a certain pressure on, developing a mission that quickly, but we lost only one day in that time, when our launch was delayed.

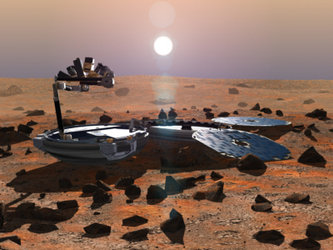

And because we're doing so much in a single mission, there are lots of demanding procedures ahead. On 19 December, we have to line up Beagle 2 directly with its landing site, because the lander has no way to steer itself. After that we'll be on collision course with Mars, so we have to repoint ourselves 400 kilometres or so above the planet, so we can be captured in Martian orbit on Christmas Day.

I work with such a fantastic team of people. I'm very proud of them.

ESA: What drives you about your job?

Michael McKay

What motivates me most is the opportunity to work with such a fantastic team of people. I'm very proud of them. The core Mars Express team at ESOC is about 35 people strong, and we've shown we work very well together.

We've been running simulation sessions twice a week, running through all the possible contingencies. These can be pretty demanding, with up to six failures in a day. Simulations work just like real life – we see the telemetry on our screens, and everything is modelled, even down to the push of sunlight on the spacecraft.

One recent simulation had us just 12 hours from Mars Orbit Insertion and the main engine was leaking fuel, so firing it would have blown the spacecraft apart. So we had to work out precisely how to cope with that. That was all worked out and uplinked successfully within ten hours.

We've been through a lot in real life too. October's solar flares gave us a lot of trouble, and we came up with a way to trick the spacecraft not to shut down. Our primary star tracker used for attitude control was dazzled by charged particles, so the normal procedure is the spacecraft would switch to the other star tracker. Then when it found that one had failed too, the spacecraft goes into 'safe' mode.

But we couldn't let that happen, because when Mars Express comes out of safe mode, the first thing is does is check its star trackers – and if they aren't working it will shut down again. The high-gain antenna could have drifted out of contact with Earth and we might have lost contact with the spacecraft for weeks.

So instead, every time Mars Express finished checking its back-up star tracker we instructed it to double-check its primary star tracker, and kept it going in this loop for a day until the sky cleared and the star trackers worked normally again.

ESA: Does Mars hold a particular fascination for you?

Michael McKay

My interest has grown over the course of the mission. Mars has a definite hold over the public imagination. In a lot of ways it is the most Earth-like of all the planets, with weather and seasonal variations. It may have once had a magnetic field like Earth's, but that has gone now and the planet's surface is unshielded from harmful radiation.

But some life might survive there still, based on what we know about terrestrial extremophiles – micro-organisms that inhabit some of the most inhospitable environments on Earth, such as volcanic vents deep under the ocean. Searching for life on Mars goes to the heart of understanding ourselves and our place in the universe – is Earth really the only place in the universe to have life?

I can remember as a child being fascinated sitting up in the early morning seeing Apollo astronauts work on the lunar surface.

ESA: How did you first become involved in space?

Michael McKay

I always wanted to work in space. I can remember as a child being fascinated sitting up in the early morning seeing Apollo astronauts work on the lunar surface. There I was wrapped in a blanket on the sofa, watching television broadcasts live from the Moon! I trained as an aeronautical engineer and was certain I wanted to work for either NASA or ESA. In the event, I got a place at ESTEC.

ESA: How would you advise someone thinking of working in the space field?

Michael McKay

I'd offer encouragement, though I don't think anyone thinking about it really needs much encouragement! Everyone I meet working in the field feels enthusiastic about taking part in the exploration of the Solar System, and the sheer excitement of it is quite something.