Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

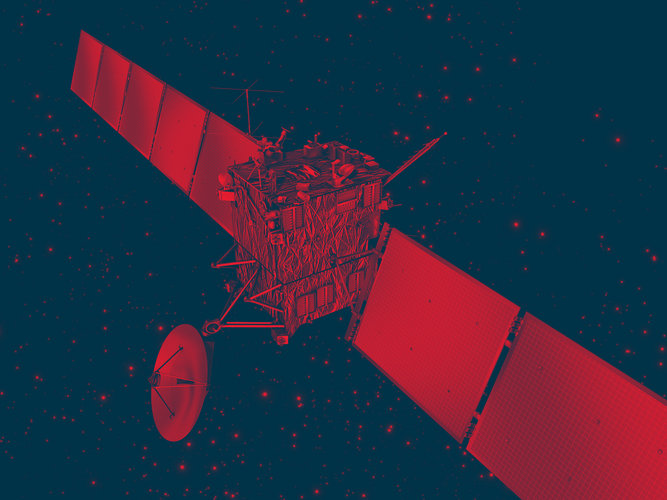

ESA's Rosetta mission chased down Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko for ten years. The comet is a regular visitor to the inner Solar System, orbiting the Sun once every 6.5 years between the orbits of Jupiter and Earth.

Like all comets, Churyumov-Gerasimenko is named after its discoverers. It was first observed in 1969, when several astronomers from Kiev visited the Alma-Ata Astrophysical Institute in Kazakhstan to conduct a survey of comets.

On 20 September, Klim Churyumov was examining a photograph of comet 32P/Comas Solá, taken by Svetlana Gerasimenko, when he noticed another comet-like object. After returning to Kiev, he studied the plate very carefully and eventually realised that they had indeed discovered a new comet.

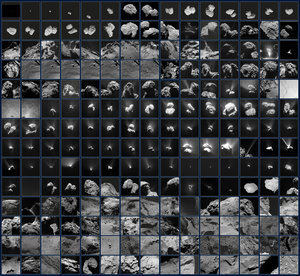

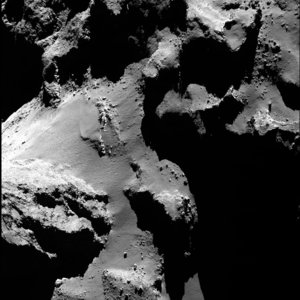

The comet was since observed from Earth on its subsequent approaches to the Sun: in 1969, 1976, 1982, 1989, 1996, 2002 and 2009, as well as during the active phase of the Rosetta mission. It was also imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2003, which allowed the first estimates of its size and shape to be made – an irregular object roughly 3 x 5 km across.

Most of the time, however, its faint image is drowned in a sea of stars, making observations with Earth-based telescopes extremely difficult. However, during its short-lived excursions to the inner Solar System, the warmth of the Sun causes ices on its surface to evaporate and jets of gas to blast dust grains into the surrounding space.

Although this enveloping ‘coma’ of dust and gas increases 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko’s brightness, it also completely hides the comet’s nucleus to ground-based observers.

Rosetta's task was to rendezvous with the comet while it still lingers in the cold regions of the Solar System, about 3.5 AU from the Sun, and to deploy a lander to reveal in close-up detail exactly what the surface looks like.

Ground-based observations indicated that, if the activity of 67P was consistent from orbit to orbit, then Rosetta would return images of an active nucleus when it rendezvoused with the comet. Over the following year, as the comet approached the Sun, Rosetta mapped its surface and studied changes in its activity. As its ices evaporated, instruments on board the orbiter studied the dust and gas particles that surround the comet and trail behind it as streaming tails, as well as their interaction with the solar wind.

Rosetta also helped identify which regions of the nucleus were more active than others. As is the case with most comets, activity is not evenly distributed on the surface of the nucleus.

To ensure the spacecraft was kept safe during times of high activity, its orbit around the comet was adjusted accordingly.