First extrasolar planets, now extrasolar moons!

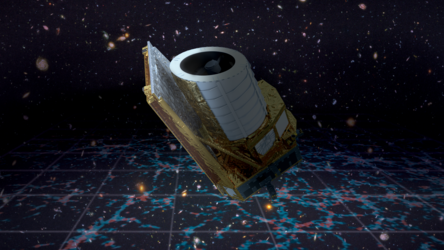

ESA is now planning a mission that can detect moons around planets outside our Solar System, those orbiting other stars.

Everyone knows our Moon: lovers stare at it, wolves howl at it, and ESA recently sent SMART-1 to study it. But there are over a hundred other moons in our Solar System, each a world in its own right.

A moon is a natural body that travels around a planet. Moons are a by-product of planetary formation and can range in size from small asteroid-sized bodies of a few kilometres in diameter to several thousand kilometres, larger even than the planets Mercury and Pluto.

Landing on another moon

One such large moon is Titan, the target for ESA’s daring Huygens mission that in 2005 will become the first spacecraft ever to land on a moon of another planet. Titan is slightly bigger than the planet Mercury, and is only called a moon because it orbits the giant planet Saturn rather than the Sun.

Four other large moons can be found around another of our neighbours, Jupiter. These are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. Europa has captured attention because beneath its icy surface, scientists think that an ocean covers the entire moon. Some scientists have even speculated that microscopic life might be found in that ocean.

Habitable moons?

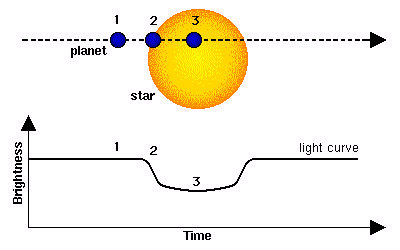

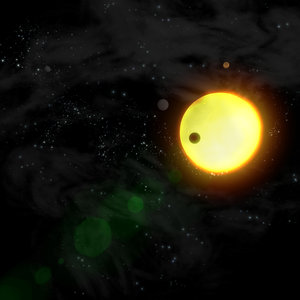

In 2008, ESA plans to launch its ‘rocky planet’ finder Eddington. By detecting the drop in light seen when a world passes in front of its parent star, Eddington will be capable of discovering planets the size of Jupiter, and also those smaller than Mars.

That means, if our own Solar System is anything to go by, it will be capable of detecting moons similar in size to Titan and the four large moons of Jupiter.

It would be particularly exciting if such combinations of planets and moons were found orbiting a star at Earth’s distance from the Sun. Perhaps then the surfaces of the moons would be warmed to habitable levels.

Orbital dancing

What about moons similar to our own? An equivalent of Earth’s moon would be too small to be detected directly by Eddington, but such a body would affect the way its planet moves and it is that movement which Eddington could detect.

The Earth and the Moon orbit the Sun like ballroom dancers who move around the floor, simultaneously twirling about one another. This means the Earth does not follow a strictly circular path through space, sometimes it will be leading the Moon and sometimes trailing.

This causes variations of up to five minutes from where the Earth would be if it did not possess a moon. By precisely timing when a rocky planet passes in front of its star, Eddington will be able to show if a moon is pulling its planet out of a strictly circular path around the star.

So, how many moons can Eddington expect to find circling planets around other stars? If we make an estimate based on our own Solar System, several thousands will be found — however, no one knows for sure. That’s what makes the quest so exciting!

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland