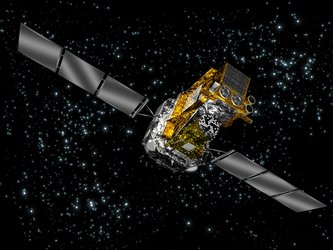

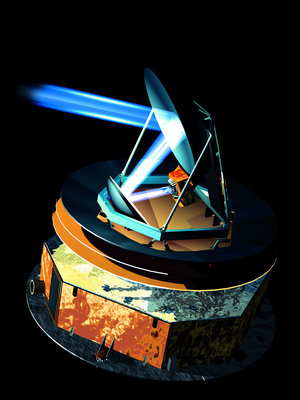

ESA’s ‘rapid reaction force’

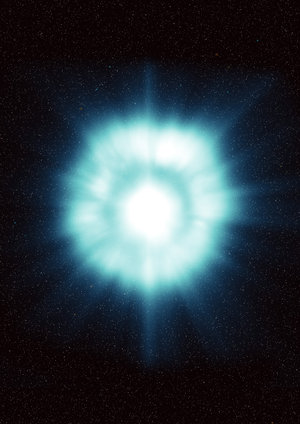

On 3 December 2003, at 22:01 UT, the blast from a massive cosmic explosion washed over the Earth and ESA’s orbiting gamma-ray observatory, Integral. Seconds later, thanks to some ingenious computer software, astronomers knew about the explosion and exactly where to point their telescopes.

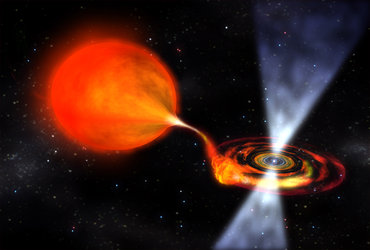

Gamma-ray bursts explode at random throughout the Universe. They usually last for less than a minute and astronomers believe that they are produced when massive stars explode in distant galaxies.

Rapid follow-up observations of gamma-ray bursts are crucial because of the speed with which they fade.

ESA has set a new record for speed and accuracy with the latest performance of the Integral Burst Alert System (IBAS). As well as the 3 December burst, which IBAS located in 18 seconds, another burst on 6 January 2004 was detected, localised and an alert sent to astronomers in just 12 seconds.

In both cases, the localisation accuracy was of only three arcminutes, a precision which, using data from other satellites, has so far only been achieved after much longer time delays.

The IBAS software is the brainchild of Sandro Mereghetti, Istituto di Astrofisica Spaziale e Fisica Cosmica (IASF), Milano, and his collaborators. Although Integral was not originally conceived to be a gamma-ray burst ‘watchdog’, scientists realised that it could perform this task if assisted by sufficiently powerful software.

The IBAS software, running at the Integral Science Data Centre (ISDC) in Versoix, Switzerland, automatically scans the Integral data, recognising gamma-ray bursts and determining their precise location. Then it instantaneously e-mails the news to astronomers, observatories and automated telescopes around the world.

It also sends an SMS text message to the cell phones of Mereghetti and other astronomers at both the IASF-Milano and the ISDC. They analyse the data manually, extracting even more information, such as the brightness of the burst, and the way it is fading. On 3 December, Mereghetti was just climbing into bed when his phone rang, signalling that his working day was not yet over!

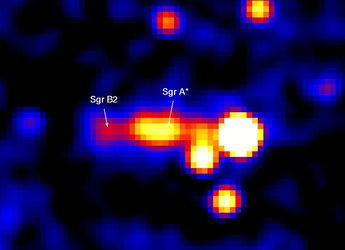

Many more scientists have already reaped the benefits of such a rapid response. The December burst information was immediately sent also to astronomers controlling another ESA orbiting observatory, XMM-Newton.

They set about reprogramming the X-ray observatory with a new sequence of observations and commands to study the gamma-ray burst. As a result, within a few hours, they found expanding rings of X-rays around the gamma-ray burst that no one had seen before.

During the first year of Integral’s scientific operation, IBAS has seen eight bursts. “We want to see more than that,” says Mereghetti.

So, the next step for the team is to make the system more sensitive because there are more faint gamma-ray bursts than bright ones.

IBAS will continue to run throughout Integral’s operational lifetime, which will be until at least 2008.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland