Accept all cookies Accept only essential cookies See our Cookie Notice

About ESA

The European Space Agency (ESA) is Europe’s gateway to space. Its mission is to shape the development of Europe’s space capability and ensure that investment in space continues to deliver benefits to the citizens of Europe and the world.

Highlights

ESA - United space in Europe

This is ESA ESA facts Member States & Cooperating States Funding Director General Top management For Member State Delegations European vision European Space Policy ESA & EU Space Councils Responsibility & Sustainability Annual Report Calendar of meetings Corporate newsEstablishments & sites

ESA Headquarters ESA ESTEC ESA ESOC ESA ESRIN ESA EAC ESA ESAC Europe's Spaceport ESA ESEC ESA ECSAT Brussels Office Washington OfficeWorking with ESA

Business with ESA ESA Commercialisation Gateway Law at ESA Careers Cyber resilience at ESA IT at ESA Newsroom Partnerships Merchandising Licence Education Open Space Innovation Platform Integrity and Reporting Administrative Tribunal Health and SafetyMore about ESA

History ESA Historical Archives Exhibitions Publications Art & Culture ESA Merchandise Kids Diversity ESA Brand Centre ESA ChampionsLatest

Space in Member States

Find out more about space activities in our 23 Member States, and understand how ESA works together with their national agencies, institutions and organisations.

Science & Exploration

Exploring our Solar System and unlocking the secrets of the Universe

Go to topicAstronauts

Missions

Juice Euclid Webb Solar Orbiter BepiColombo Gaia ExoMars Cheops Exoplanet missions More missionsActivities

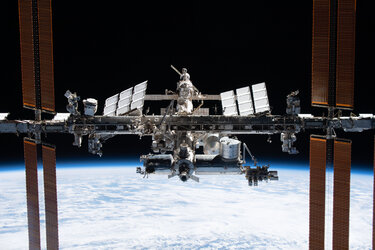

International Space Station Orion service module Gateway Concordia Caves & Pangaea BenefitsLatest

Space Safety

Protecting life and infrastructure on Earth and in orbit

Go to topicAsteroids

Asteroids and Planetary Defence Asteroid danger explained Flyeye telescope: asteroid detection Hera mission: asteroid deflection Near-Earth Object Coordination CentreSpace junk

About space debris Space debris by the numbers Space Environment Report In space refuelling, refurbishing and removingSafety from space

Clean Space ecodesign Zero Debris Technologies Space for Earth Supporting Sustainable DevelopmentApplications

Using space to benefit citizens and meet future challenges on Earth

Go to topicObserving the Earth

Observing the Earth Future EO Copernicus Meteorology Space for our climate Satellite missionsCommercialisation

ESA Commercialisation Gateway Open Space Innovation Platform Business Incubation ESA Space SolutionsLatest

Enabling & Support

Making space accessible and developing the technologies for the future

Go to topicBuilding missions

Space Engineering and Technology Test centre Laboratories Concurrent Design Facility Preparing for the future Shaping the Future Discovery and Preparation Advanced Concepts TeamSpace transportation

Space Transportation Ariane Vega Space Rider Future space transportation Boost! Europe's Spaceport Launches from Europe's Spaceport from 2012Latest

Planck’s flame-filled view of the Polaris Flare

Thank you for liking

You have already liked this page, you can only like it once!

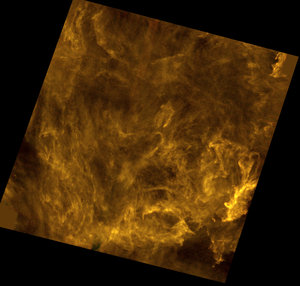

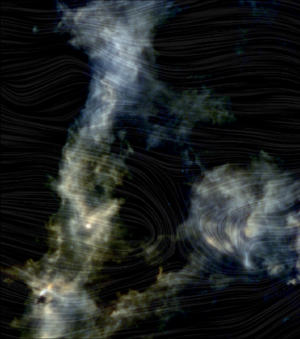

This image from ESA’s Planck satellite appears to show something quite ethereal and fantastical: a sprite-like figure emerging from scorching flames and walking towards the left of the frame, its silhouette a blaze of warm-hued colours.

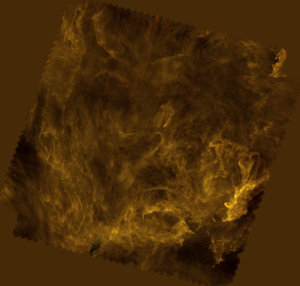

This fiery illusion is actually a celestial feature named the Polaris Flare. This name is somewhat misleading; despite its moniker, the Polaris Flare is not a flare but a 10 light-year-wide bundle of dusty filaments in the constellation of Ursa Minor (The Little Bear), some 500 light-years away.

The Polaris Flare is located near the North Celestial Pole, a perceived point in the sky aligned with Earth’s spin axis. Extended into the skies of the northern and southern hemispheres, this imaginary line points to the two celestial poles. To find the North Celestial Pole, an observer need only locate the nearby Polaris (otherwise known as the North Star or Pole Star), the brightest star in the constellation of Ursa Minor.

Some of the secrets of the Polaris Flare were uncovered when it was observed by ESA’s Herschel some years ago. Using a combination of such Herschel observations and a computer simulation, scientists think that the Polaris Flare filaments could have been formed as a result of slow shockwaves pushing their way through a dense interstellar cloud, an accumulation of cold cosmic dust and gas sitting between the stars of our Galaxy.

These shockwaves, reminiscent of the sonic booms formed by fast sound waves here on Earth, would have been themselves triggered by nearby exploding stars that disrupted their surroundings as they died, triggering cloud-wide waves of turbulence

These shockwaves, reminiscent of the sonic booms formed by fast sound waves here on Earth, were themselves triggered by nearby exploding stars that disrupted their surroundings as they died, triggering cloud-wide waves of turbulence. These waves swept up the gas and dust in their path, sculpting the material into the snaking filaments we see.

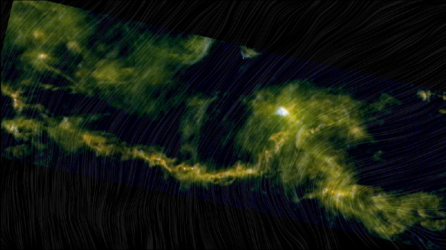

This image is not a true-colour view, nor is it an artistic impression of the Flare, rather it comprises observations from Planck, which operated between 2009 and 2013. Planck scanned and mapped the entire sky, including the plane of the Milky Way, looking for signs of ancient light (known as the cosmic microwave background) and cosmic dust emission. This dust emission allowed Planck to create this unique map of the sky – a magnetic map.

The relief lines laced across this image show the average direction of our Galaxy’s magnetic field in the region containing the Polaris Flare. This was created using the observed emission from cosmic dust, which was polarised (constrained to one direction). Dust grains in and around the Milky Way are affected by and interlaced with the Galaxy’s magnetic field, causing them to align preferentially in space. This carries through to the dust’s emission, which also displays a preferential orientation that Planck could detect.

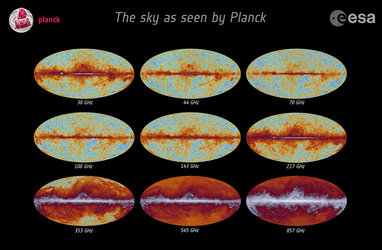

The emission from dust is computed from a combination of Planck observations at 353, 545 and 857 GHz, whereas the direction of the magnetic field is based on Planck polarisation data at 353 GHz. This frame has an area of 30 x 30º on the sky, and the colours represent the intensity of dust emission.

-

CREDIT

ESA and the Planck Collaboration -

LICENCE

ESA Standard Licence

Interstellar filaments in the Polaris Flare

Taurus Molecular Cloud viewed by Herschel and Planck

The Polaris filament network

Planck all-sky frequency maps

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland