Accept all cookies Accept only essential cookies See our Cookie Notice

About ESA

The European Space Agency (ESA) is Europe’s gateway to space. Its mission is to shape the development of Europe’s space capability and ensure that investment in space continues to deliver benefits to the citizens of Europe and the world.

Highlights

ESA - United space in Europe

This is ESA ESA facts Member States & Cooperating States Funding Director General Top management For Member State Delegations European vision European Space Policy ESA & EU Space Councils Responsibility & Sustainability Annual Report Calendar of meetings Corporate newsEstablishments & sites

ESA Headquarters ESA ESTEC ESA ESOC ESA ESRIN ESA EAC ESA ESAC Europe's Spaceport ESA ESEC ESA ECSAT Brussels Office Washington OfficeWorking with ESA

Business with ESA ESA Commercialisation Gateway Law at ESA Careers Cyber resilience at ESA IT at ESA Newsroom Partnerships Merchandising Licence Education Open Space Innovation Platform Integrity and Reporting Administrative Tribunal Health and SafetyMore about ESA

History ESA Historical Archives Exhibitions Publications Art & Culture ESA Merchandise Kids Diversity ESA Brand Centre ESA ChampionsSpace in Member States

Find out more about space activities in our 23 Member States, and understand how ESA works together with their national agencies, institutions and organisations.

Science & Exploration

Exploring our Solar System and unlocking the secrets of the Universe

Go to topicAstronauts

Missions

Juice Euclid Webb Solar Orbiter BepiColombo Gaia ExoMars Cheops Exoplanet missions More missionsActivities

International Space Station Orion service module Gateway Concordia Caves & Pangaea BenefitsLatest

Space Safety

Protecting life and infrastructure on Earth and in orbit

Go to topicAsteroids

Asteroids and Planetary Defence Asteroid danger explained Flyeye telescope: asteroid detection Hera mission: asteroid deflection Near-Earth Object Coordination CentreSpace junk

About space debris Space debris by the numbers Space Environment Report In space refuelling, refurbishing and removingSafety from space

Clean Space ecodesign Zero Debris Technologies Space for Earth Supporting Sustainable DevelopmentApplications

Using space to benefit citizens and meet future challenges on Earth

Go to topicObserving the Earth

Observing the Earth Future EO Copernicus Meteorology Space for our climate Satellite missionsCommercialisation

ESA Commercialisation Gateway Open Space Innovation Platform Business Incubation ESA Space SolutionsLatest

Enabling & Support

Making space accessible and developing the technologies for the future

Go to topicBuilding missions

Space Engineering and Technology Test centre Laboratories Concurrent Design Facility Preparing for the future Shaping the Future Discovery and Preparation Advanced Concepts TeamSpace transportation

Space Transportation Ariane Vega Space Rider Future space transportation Boost! Europe's Spaceport Launches from Europe's Spaceport from 2012Latest

Summer fireworks on Rosetta’s comet

Thank you for liking

You have already liked this page, you can only like it once!

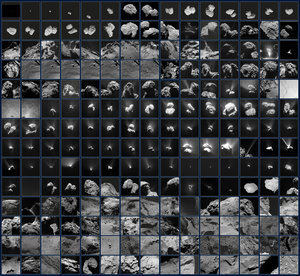

Blink and you might have missed them. But thanks to the cadence at which Rosetta took images of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko during its most active period in August 2015, scientists watching for brief but powerful outbursts caught plenty. Thirty-four no less, in the three months centred around the comet’s closest approach to the Sun, which occurred nearly two years ago, on 13 August 2015.

The increase in solar energy during these months warmed the comet’s frozen ices, turning them to gas, which subsequently poured out into space, dragging dust along with it. The violent, transient events occurred over and above regular jets and flows of material seen streaming from the comet’s nucleus, and were much brighter. Although typically only lasting a few minutes, some 60–260 tonnes of comet material could be released.

As can be seen from the montage shown here, some outbursts were long, narrow jets extending far from the comet nucleus, while others had a broader base that expanded more laterally. Others seem to be a hybrid of the two.

Scientists studying the outbursts even traced them back to their origins on the surface. Some were found to be linked to changes in local temperatures, perhaps in the early morning after many hours of darkness, or later in the day after several hours of heating, while others came from areas associated with pits or steep cliffs.

The images seen here are from both the high-resolution OSIRIS camera, and from the spacecraft’s navigation camera. Browse more images from Rosetta’s mission via ESA’s Archive Image Browser.

Rosetta arrived at the comet on 6 August 2014 and released its lander Philae on 12 November 2014. Rosetta followed the comet around the Sun for just over two years, watching the rise and fall of its activity over time and returning a wealth of scientific data from its suite of in situ and remote sensing instruments. It concluded its pioneering mission on 30 September 2016 by descending on to the comet’s surface in a controlled impact.

-

CREDIT

OSIRIS: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA; NavCam: ESA/Rosetta/NavCam – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 -

LICENCE

ESA Standard Licence

29 July outburst context

Guide to comet activity

Rosetta’s ever-changing view of a comet

Outburst in action

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland