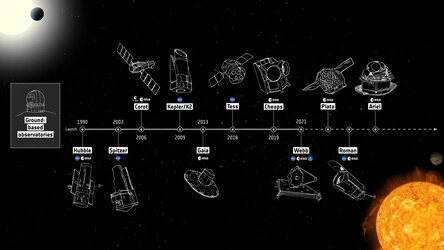

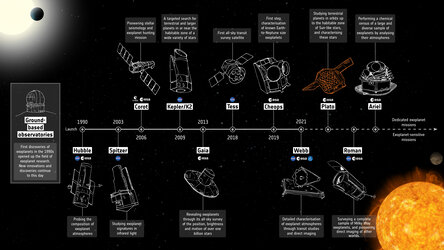

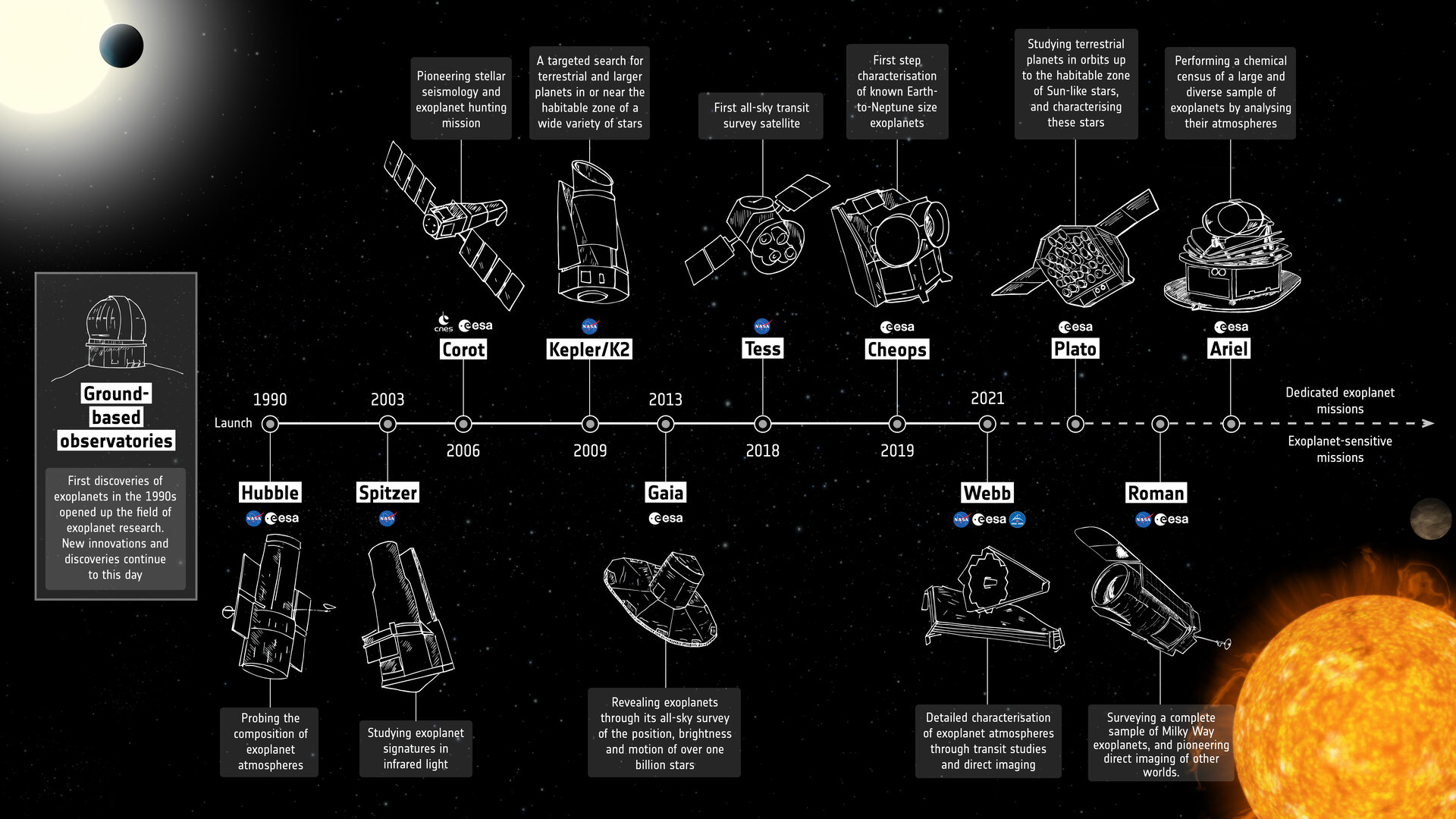

Exoplanet mission timeline

The first discoveries of exoplanets in the 1990s, by ground-based observatories, completely changed our perspective of the Solar System and opened up new areas of research that continue to be studied today. This infographic highlights the main space-based contributors to the field, including not only exoplanet-dedicated missions, but also exoplanet-sensitive missions, past, present and future.

One of the first exoplanet-sensitive space telescopes was the CNES-led Convection, Rotation and planetary Transits mission, CoRoT, which launched in 2006. CoRoT was the first space mission dedicated to exoplanetary research and designed for this purpose. It uncovered exoplanets using the transit method and determined the structure, inner processes and ages of thousands of stars.

NASA’s 2009 Kepler mission was an exoplanet discovery machine, accounting for around three-quarters of all exoplanet discoveries so far. It looked at a specific patch of sky for a lengthy period of time, so was sensitive to a great number of faint stars. It’s NASA successor TESS, Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, was launched in April 2018 and continues its effort. It is the first all-sky transit survey satellite.

Meanwhile, telescopes that were launched even before the first discoveries were confirmed, such as the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and the NASA Spitzer mission, have been contributing to the evolving field. The new NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope continues the legacy of exoplanet research by missions not designed solely for it.

ESA’s Gaia mission, through its unprecedented all-sky survey of the position, brightness and motion of over one billion stars, is providing a large database to search for exoplanets. These will be uncovered through the changes in the star’s motion as the planet or planets orbit around it, or by the dip in the star’s brightness as the planet transits across its face.

But discovering an exoplanet is just the beginning: dedicated telescopes are needed to follow up on this ever-growing catalogue to understand their properties, to get closer to knowing if another Earth-like planet exists, and better understanding what conditions are needed for planet formation and the emergence of life.

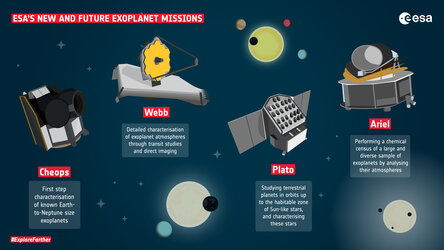

ESA is leading three dedicated exoplanet satellites, each tackling a unique topic.

The Characterising Exoplanet Satellite, Cheops, was launched in 2019 and is observing bright stars known to host exoplanets, in particular Earth-to-Neptune-sized planets, anywhere in the sky. By knowing exactly where and when to look for transits, and repeatedly returning to observe the same targets, Cheops is currently one of the most efficient instruments to study individual exoplanets. It records the precise sizes of these relatively small planets and together with mass measurements calculated from other observatories, enables the determination of the planet’s density and even atmospheres, and thus make a first-step characterisation of the nature of these worlds.

Cheops is also identifying candidates for additional study by future missions. For example, it provides well-characterised targets for the international James Webb Space Telescope, which will perform further detailed studies of exoplanets’ atmospheres.

The next upcoming mission is Plato, the PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars mission, planned to launch in 2026. Plato is a next-generation planet hunter with an emphasis on the properties of rocky planets up to the habitable zone around sunlike stars – the region around a star where liquid water can exist on a planet’s surface. Plato will provide the largest catalogue of exoplanets down to the size of Earth with known size, mass, age and orbit parameters. Importantly, Plato will also analyse properties of the planet’s host star, including its age which will give insight into the evolutionary state of entire extrasolar systems.

Ariel, the Atmospheric Remote-Sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey mission, is foreseen for launch in 2029. It will perform the first chemical census of a large and diverse sample of exoplanets by analysing the composition of their atmospheres in great detail. Ariel will help understand what planets are made of, and how they form and evolve. Ariel is not alone in its efforts as the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope is equipped to help with the characterisation efforts of exoplanetary atmospheres.

Characterisation is essential, but the hunt for unknown exoplanets is still ongoing with the NASA/ESA Roman mission, which will use the technique of gravitational microlensing to find distant exoplanets.

With the complementary work of both ground- and space-based observatories, we will get closer to understanding one of humanity’s biggest questions: are we alone in the Universe?

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland