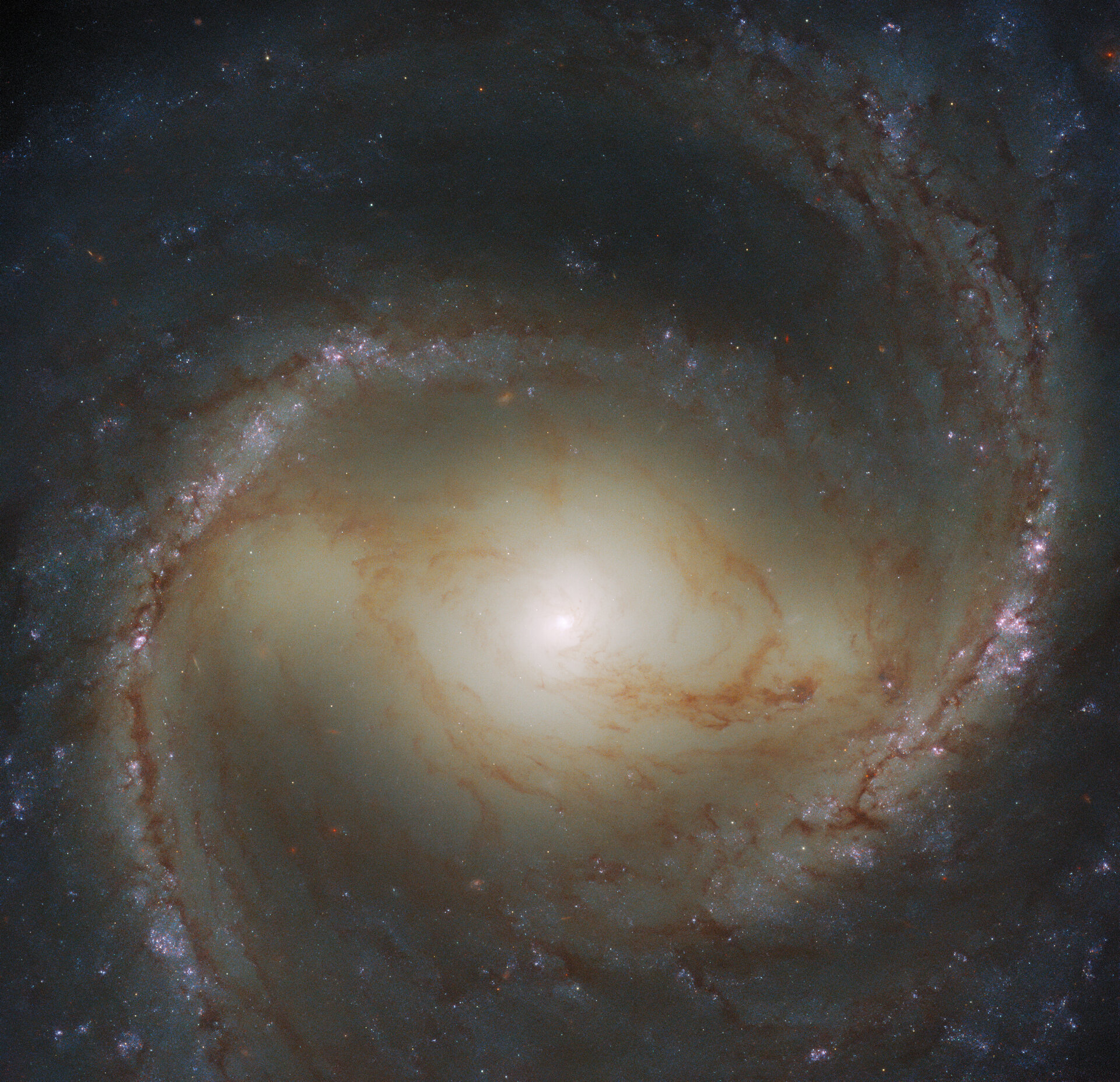

Spiral snapshot

The spiral galaxy M91 fills the frame of this Wide Field Camera 3 observation from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. M91 lies approximately 55 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Coma Berenices and — as is evident in this image — is a barred spiral galaxy. While M91’s prominent bar makes for a spectacular galactic portrait, it also hides an astronomical monstrosity. Like our own galaxy, M91 contains a supermassive black hole at its centre. A 2009 study using archival Hubble data found that this central black hole weighs somewhere between 9.6 and 38 million times as much as the Sun.

Whilst archival Hubble data allowed astronomers to weigh M91’s central black hole, more recent observations have had other scientific aims. This observation is part of an effort to build a treasure trove of astronomical data exploring the connections between young stars and the clouds of cold gas in which they form. To do this, astronomers used Hubble to obtain ultraviolet and visible observations of galaxies already seen at radio wavelengths by the ground-based Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

Observing time with Hubble is a highly valued, and much sought-after, resource for astronomers. To obtain data from the telescope, astronomers first have to write a proposal detailing what they want to observe and highlighting the scientific importance of their observations. These proposals are then anonymised and judged on their scientific merit by a variety of astronomical experts. This process is incredibly competitive: following Hubble’s latest call for proposals, only around 13% of the proposals were awarded observing time.