Space brings fresh water to Morocco

Recycling waste water and urine into drinking water is not only for astronauts – the same method is now treating groundwater for a school in Morocco.

The village of Sidi Taïbi near Kenitra, 30 km from Morroco’s capital city Rabat, has grown rapidly in recent years, and providing fresh water to its inhabitants is difficult because the groundwater is so rich in nitrates and fertiliser it is unsuitable for human consumption.

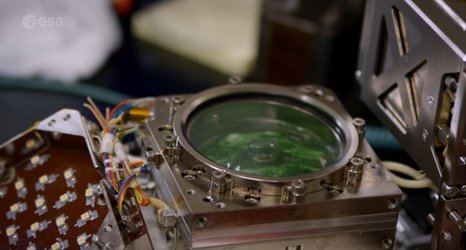

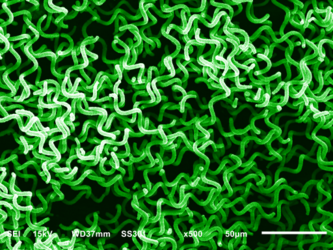

ESA has been working for over 20 years on the best recipe for a closed life-support system that processes waste and delivers fresh oxygen, food and water to astronauts. One of the discoveries is how to build and control organic and ceramic membranes with holes just one ten-thousandth of a millimetre across – 700 times thinner than a strand of human hair. These tiny pores can filter out unwanted compounds in water, in particular nitrate.

With help from a UNESCO partnership, the University of Kenitra looked to apply this new approach to tackle their drinking-water problem.

Building on ESA’s experience with membranes, French company Firmus teamed up with Germany’s Belectric to build a self-sustaining unit powered by solar panels and wind energy.

From Antarctica to Morocco to space

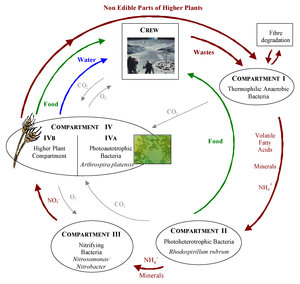

The more that astronauts can recycle, the fewer supplies they need to pack for space. One solution ESA is working on is to use bacteria, algae, filters and high-technology together so the organisms produce oxygen, water and food from waste.

The trick is finding the right techniques and combining them in a single package. Along the way, ESA’s life-support team have studied a number of novel methods, from cholesterol-reducing bacteria to bubbly-wine production.

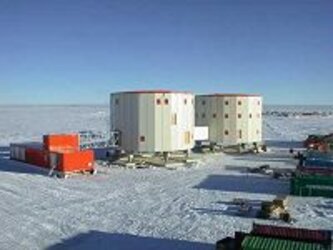

The organic membranes in Sidi Taïbi have already proven their worth in very different circumstances – at the other end of the world, in Antarctica. The Concordia research base, 1600 km from the South Pole, uses water filtration to recycle waste water from showers, washing machines and dishwashers.

Working since 2005, it has required very little maintenance. Up to 16 people live at Concordia base, while the new treatment facility in Morocco will cater for 1200 students. Surplus energy and water generated during school holidays will be shared with locals.

If the membrane approach works well in Morocco, the unit will be scaled up by a factor of ten to deliver water to the rest of the local population.