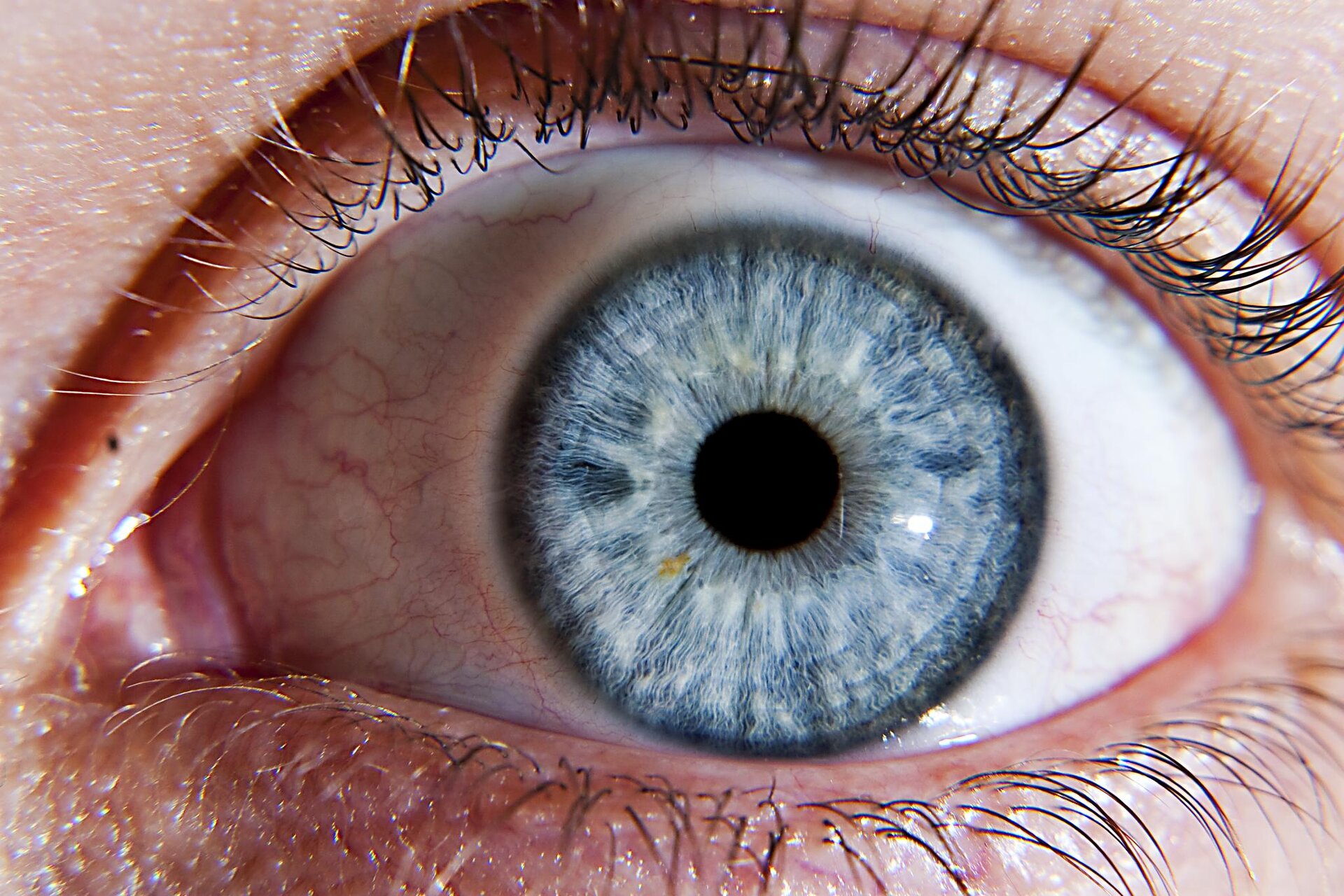

Eye-catching space technology restoring sight

Laser surgery to correct eyesight is common practice, but did you know that technology developed for use in space is now commonly used to track the patient’s eye and precisely direct the laser scalpel?

If you look at a fixed point while tilting or shaking your head, your eyes automatically hold steady, allowing you to see clearly even while moving around. This neat trick of nature is a reflex and we are usually unaware that it even happens.

Behind the scenes, your brain is constantly interpreting information from the inner ear to maintain balance and stable vision. An essential feature of this sensory system is the use of gravity as a reference. Most species on Earth, going back as far as the dinosaurs, rely on it.

But how do astronauts in space cope when the inner ear can no longer rely on gravity? How well do astronauts focus on a computer screen when floating by, and how do they judge speed?

To investigate these questions, a team led by Professor Andrew Clarke based in Berlin, Germany, designed a series of experiments to measure astronauts’ eye movements as they worked on the International Space Station.

Researchers needed a robust method to track the eyes without interfering with the astronaut’s normal work. The answer came in the form of a helmet feeding high-performance image-processing chips similar to those found in consumer cameras.

Lost in space

Ten years ago the first astronauts used the device on the Space Station, followed by more than four years of experiments.

The results showed that our balance and the overall control of eye movements are indeed affected by weightlessness. These two systems work closely together under normal gravity conditions, but become somewhat dissociated in microgravity.

The findings point to the entire sensory-motor complex and spatial perception relying on gravity as a reference for orientation. After a flight, it takes several days to weeks for the astronauts to return to normal.

Back to Earth

In parallel with its use on the Space Station, the engineers realised the device had potential for applications on Earth. Tracking the eye’s position without interfering with the surgeon’s work is essential in laser surgery. The space technology proved ideal.

“This eye-tracking equipment is being used in a large proportion of corrective laser surgeries throughout the world,” explains Prof. Clarke.

“In addition, a commercially available version has also been delivered to a large number of research laboratories in Europe and North America for ground-based studies.