Getting to know Rosetta’s comet

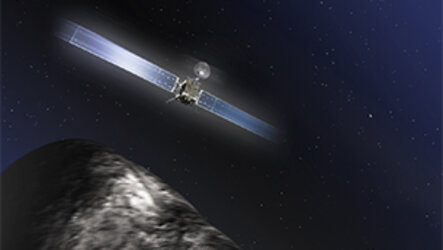

Rosetta is revealing its host comet as having a remarkable array of surface features and with many processes contributing to its activity, painting a complex picture of its evolution.

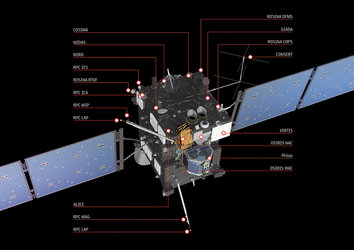

In a special edition of the journal Science, initial results are presented from seven of Rosetta’s 11 science instruments based on measurements made during the approach to and soon after arriving at Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in August 2014.

The familiar shape of the dual-lobed comet has now had many of its vital statistics measured: the small lobe measures 2.6 × 2.3 × 1.8 km and the large lobe 4.1 × 3.3 × 1.8 km. The total volume of the comet is 21.4 km3 and the Radio Science Instrument has measured its mass to be 10 billion tonnes, yielding a density of 470 kg/m3.

By assuming an overall composition dominated by water ice and dust with a density of 1500–2000 kg/m3, the Rosetta scientists show that the comet has a very high porosity of 70–80%, with the interior structure likely comprising weakly bonded ice-dust clumps with small void spaces between them.

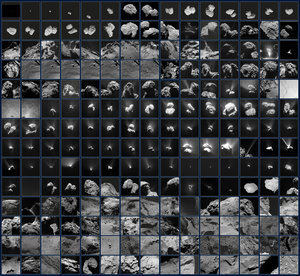

The OSIRIS scientific camera, has imaged some 70% of the surface to date: the remaining unseen area lies in the southern hemisphere that has not yet been fully illuminated since Rosetta’s arrival.

The scientists have so far identified 19 regions separated by distinct boundaries and, following the ancient Egyptian theme of the Rosetta mission, these regions are named for Egyptian deities, and are grouped according to the type of terrain dominant within.

Five basic – but diverse – categories of terrain type have been determined: dust-covered; brittle materials with pits and circular structures; large-scale depressions; smooth terrains; and exposed more consolidated (‘rock-like’) surfaces.

Much of the northern hemisphere is covered in dust. As the comet is heated, ice turns directly into gas that escapes to form the atmosphere or coma. Dust is dragged along with the gas at slower speeds, and particles that are not travelling fast enough to overcome the weak gravity fall back to the surface instead.

Some sources of discrete jets of activity have also been identified. While a significant proportion of activity emanates from the smooth neck region, jets have also been spotted rising from pits.

The gases that escape from the surface have also been seen to play an important role in transporting dust across the surface, producing dune-like ripples, and boulders with ‘wind-tails’ – the boulders act as natural obstacles to the direction of the gas flow, creating streaks of material ‘downwind’ of them.

Continue reading below

The dusty covering of the comet may be several metres thick in places and measurements of the surface and subsurface temperature by the Microwave Instrument on the Rosetta Orbiter, or MIRO, suggest that the dust plays a key role in insulating the comet interior, helping to protect the ices thought to exist below the surface.

Small patches of ice may also be present on the surface. At scales of 15–25 m, Rosetta’s Visible, InfraRed and Thermal Imaging Spectrometer, or VIRTIS, finds the surface to be compositionally very homogenous and dominated by dust and carbon-rich molecules, but largely devoid of ice. But smaller, bright areas seen in images are likely to be ice-rich. Typically, they are associated with exposed surfaces or debris piles where collapse of weaker material has occurred, uncovering fresher material.

On larger scales, many of the exposed cliff walls are covered in randomly oriented fractures. Their formation is linked to the rapid heating–cooling cycles that are experienced over the course of the comet’s 12.4-hour day and over its 6.5-year elliptical orbit around the Sun. One prominent and intriguing feature is a 500 m-long crack seen roughly parallel to the neck between the two lobes, although it is not yet known if it results from stresses in this region.

Some very steep regions of the exposed cliff faces are textured on scales of roughly 3 m with features that have been nicknamed ‘goosebumps’. Their origin is yet to be explained, but their characteristic size may yield clues as to the processes at work when the comet formed.

And on the very largest scale, the origin of the comet’s overall double-lobed shape remains a mystery. The two parts seem very similar compositionally, potentially favouring the erosion of a larger, single body. But the current data cannot yet rule out the alternative scenario: two separate comets formed in the same part of the Solar System and then merged together at a later date.

This key question will be studied further over the coming year as Rosetta accompanies the comet around the Sun.

How to grow an atmosphere

Their closest approach to the Sun occurs on 13 August at a distance of 186 million kilometres, between the orbits of Earth and Mars. As the comet continues to move closer to the Sun, an important focus for Rosetta’s instruments is to monitor the development of the comet’s activity, in terms of the amount and composition of gas and dust emitted by the nucleus to form the coma.

Images from the scientific and navigation cameras have shown an increase in the amount of dust flowing away from the comet over the past six months, and MIRO showed a general rise in the comet’s global water vapour production rate, from 0.3 litres per second in early June 2014 to 1.2 litres per second by late August. MIRO also found that a substantial portion of the water seen during this phase originated from the comet’s neck.

Water is accompanied by other outgassing species, including carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. The Rosetta Orbiter Spectrometer for Ion and Neutral Analysis, ROSINA, is finding large fluctuations in the composition of the coma, representing daily and perhaps seasonal variations in the major outgassing species. Water is typically the dominant outgassing molecule, but not always.

By combining measurements from MIRO, ROSINA and GIADA (Rosetta’s Grain Impact Analyzer and Dust Accumulator) taken between July and September, the Rosetta scientists have made a first estimate of the comet’s dust-to-gas ratio, with around four times as much mass in dust being emitted than in gas, averaged over the sunlit nucleus surface.

However, this value is expected to change once the comet warms up further and ice grains – rather than pure dust grains – are ejected from the surface.

GIADA has also been tracking the movement of dust grains around the comet, and, together with images from OSIRIS, two distinct populations of dust grains have been identified. One set is outflowing and is detected close to the spacecraft, while the other family is orbiting the comet no closer than 130 km from the spacecraft.

It is thought that the more distant grains are left over from the comet’s last closest approach to the Sun. As the comet moved away from the Sun, the gas flow from the comet decreased and was no longer able to perturb the bound orbits. But as the gas production rate increases again over the coming months, it is expected that this bound cloud will dissipate. However, Rosetta will only be able to confirm this when it is further away from the comet again – it is currently in a 30 km orbit.

As the gas–dust coma continues to grow, interactions with charged particles of the solar wind and with the Sun’s ultraviolet light will lead to the development of the comet’s ionosphere and, eventually, its magnetosphere. The Rosetta Plasma Consortium, or RPC, instruments have been studying the gradual evolution of these components close to the comet.

“Rosetta is essentially living with the comet as it moves towards the Sun along its orbit, learning how its behaviour changes on a daily basis and, over longer timescales, how its activity increases, how its surface may evolve, and how it interacts with the solar wind,” says Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist.

“We have already learned a lot in the few months we have been alongside the comet, but as more and more data are collected and analysed from this close study of the comet we hope to answer many key questions about its origin and evolution.”

Notes for Editors

These are among the very first scientific results from Rosetta and there is much more to come as the scientists work through the data and as the comet continues to evolve during its closest approach to the Sun. They are described in more detail in accompanying posts on the Rosetta blog and in the 23 January 2015 Science special edition:

“Dust Measurements in the Coma of Comet 67P/Churyumov- Gerasimenko Inbound to the Sun Between 3.7 and 3.4 AU” by A. Rotundi et al. (GIADA)

“Subsurface properties and early activity of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko” by S. Gulkis et al. (MIRO)

“The morphological diversity of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko” by N. Thomas et al. (OSIRIS)

“On the nucleus structure and activity of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko” by H. Sierks et al. (OSIRIS)

“Time variability and heterogeneity in the coma of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko,” by M. Hässig et al. (ROSINA)

“Birth of a comet magnetosphere: a spring of water ions,” by H. Nilsson et al. (RPC-ICA)

“The organic-rich surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as seen by VIRTIS/Rosetta” by F. Capaccioni et al. (VIRTIS)

"67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, a Jupiter family comet with a high D/H ratio" by K. Altwegg et al. (ROSINA)

More about Rosetta

Rosetta is an ESA mission with contributions from its Member States and NASA. Rosetta’s Philae lander was provided by a consortium led by DLR, MPS, CNES and ASI. Rosetta is the first mission in history to rendezvous with a comet. It is escorting the comet as they orbit the Sun together. Philae landed on the comet on 12 November 2014. Comets are time capsules containing primitive material left over from the epoch when the Sun and its planets formed. By studying the gas, dust and structure of the nucleus and organic materials associated with the comet, via both remote and in situ observations, the Rosetta mission should become the key to unlocking the history and evolution of our Solar System.