ESA remembers the night of the comet

Twenty-five years ago, ESA made its mark in deep space. A small spacecraft swept to within 600 km of Halley’s comet. The Giotto probe was nearly destroyed by the encounter but what it saw changed our picture of comets forever.

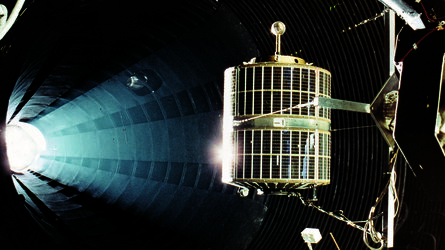

As debuts go, it doesn’t get any better than Giotto. The spacecraft was ESA’s first deep-space mission. Built to a design that drew on the Geos Earth-orbiting research satellites, it was fitted with shielding to protect it from the ‘sand-blasting’ it was going to receive as it sped through the comet’s tail.

It was originally conceived as a joint mission with NASA, the Tempel-2 Rendezvous–Halley Intercept mission. When the US pulled out after budget cuts, ESA took the bold decision to forge on, finding Japan and Russia willing to contribute their own missions. Together, they sent a flotilla, with the Russian missions serving as pathfinders to guide Giotto to its dangerous encounter.

Scientists, controllers and engineers gathered at ESA’s control centre in Darmstadt, Germany, on the night of 13–14 March 1986 to witness the flyby.

“It was a once-in-a-lifetime event and it had a big impact on the general public,” says Giotto’s former Deputy Project Scientist, Gerhard Schwehm.

The scientific harvest from Giotto changed people’s perception of comets. By measuring its composition, Giotto confirmed Halley as a primitive remnant of the Solar System, billions of years old. It detected complex molecules locked in Halley’s ices that could have provided the chemical building blocks of life on Earth.

Yet the biggest triumph was the image of Halley itself. “It may sound simple to say that but the picture was the best thing, the moment you saw it... it was tremendous,” remembers Gerhard.

Countless people have seen the ghostly shimmer of Halley’s comet from Earth. Records of it stretch back to China in 240 BC. It famously appears on the Bayeux Tapestry, and the Italian artist Giotto di Bondone used it to symbolise the star of Bethlehem in his masterpiece, The Adoration of the Magi.

But none saw what his spacecraft namesake saw: the very heart of the comet, the nucleus.

Just 10x15 km, it surprised everyone by being darker than coal, reflecting just 4% of the light falling on its surface.

Instead of the whole surface boiling away, jets were localised in specific areas.

Giotto nearly did not survive. As expected, the probe was pummelled. Dust from the comet ripped into it at speeds of 68 km/s, eroding away the shielding and the sensors, destroying the camera.

But Giotto itself lived on and was sent to meet a second comet, Grigg–Skjellerup, in 1992.

Since Giotto’s encounter, Halley has continued its journey, covering about a third of its 76-year orbit. Although it will not return until 2061, there are other cometary targets.

“Giotto ignited the planetary science community in Europe – we had demonstrated that we could successfully lead demanding missions – and people started thinking about what else we could do,” says Gerhard.

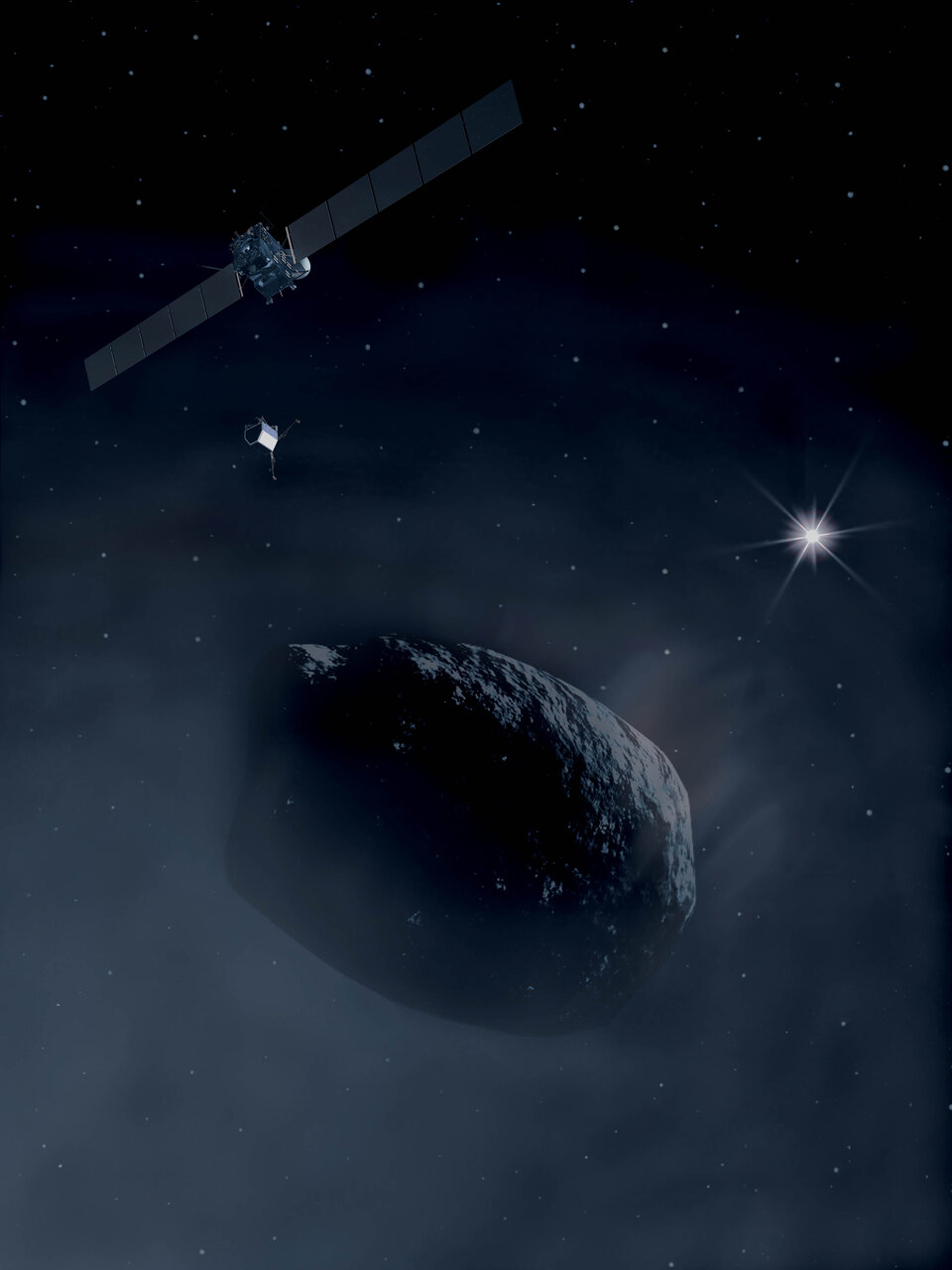

ESA’s Rosetta is next. The spacecraft is en route to comet Churyumov–Gerasimenko, for arrival in 2014. It will study the comet and release a lander to analyse the surface material.

Recently, Rosetta flew by asteroid Lutetia and is now preparing to hibernate for the rest of its cruise. Once at Churyumov–Gerasimenko, Rosetta will follow the comet for months.

Where Giotto gave us the night of the comet, Rosetta promises the year of the comet.