If at first you don't succeed....: An interview with Vittorio Formisano

Seven years ago, Prof. Vittorio Formisano had the worst day of his professional life. A malfunctioning rocket stage sent Russian planetary probe Mars '96 tumbling back down to Earth – and along with it an instrument that he and his team had worked on for almost a decade. Today, Vittorio is Principal Investigator for a new version of the same instrument – the Planetary Fourier Spectrometer (PFS) – now almost at the Red Planet on board ESA’s Mars Express.

Prof. Vittorio Formisano

Head of Research, National Council for Research's Institute of Physics and Interplanetary Space, Italy

Principal Investigator, PFS, Mars Express

Born: 24 July 1941 in Boscotrecase, Naples, Italy

PhD in Physics, University of Rome, 1965; as researcher and visiting scientist at establishments such as Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA, Mullard Space Science Laboratory, UK, University of California at Los Angeles and CNR Laboratory Plasma Spazio, Frascati, Italy, he worked on projects ranging from ESA’s HEOS 1 and 2, to NASA’s Pioneer missions.

Between 1979 and 1982, he was the ESA Study Scientist for Kepler, a proposal for a Mars orbiter, and for Giotto and Vega mission proposals to Comet Halley. Since then he has supervised Italy's participation in missions such as Cluster II.

Married with two children, (a third one from previous marriage) Vittorio enjoys gardening, orchid growing and reading fiction and non-fiction, with a particular interest in the area of ‘pedagogy’, the science of teaching.

Finally reaching Mars will represent a completion of something that has been in my life for a very long time.

ESA: Here we are, close to arriving in Mars orbit, how do you feel?

Vittorio Formisano

Well, these last few months since launch have been really tense, and the time seems to move really slowly! With Mars ’96, I've been working on this experiment for the last 16 years. The new version is a redesign of the original. And more than a quarter of a century ago I worked at ESA in the Netherlands, leading a design study for a Mars orbiter called Kepler, which would have been a mission to study the Martian atmosphere, just like PFS is designed to do. So finally reaching Mars will represent a completion of something that has been in my life for a very long time.

ESA: What first inspired you to become interested in space, and how did you enter the field?

Vittorio Formisano

When I was young I remember being very impressed by Sputnik in 1957, and later all the front pages and full-size pictures of Yuri Gagarin in the papers. I've been in the field all my working life, since 1965. After I completed my doctorate I went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, meeting Italian scientist Bruno Rossi and working on early plasma physics with results from Pioneers 5 and 6, and so on.

We still hope there could have been life on Mars, even if we know rationally there can't be any today.

ESA: What drives you in your job, and what fascinates you about Mars in particular?

Vittorio Formisano

I have spent part of my career with the technical details of designing and building experiments, but it is really the science that is important to me. As for Mars, I think even in 2003, our common human culture is still influenced by the ideas of 19th century astronomers Giovanni Schiaparelli and Percival Lowell. We still hope there could have been life on Mars, even if we know rationally there can't be any today, at least not surviving on the surface.

ESA: What do you hope to find with your experiment, and why is that important?

Vittorio Formisano

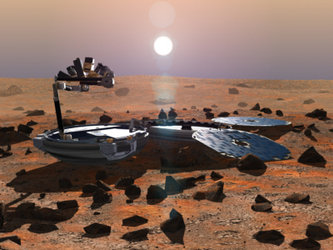

The PFS is a very high spectral resolution spectrometer studying both atmospheric and surface composition. There are a few things we particularly hope to find with it. The presence of atmospheric methane is one. If there is any at all in the Martian atmosphere it probably undergoes rapid photochemical degradation. Methane on Earth is abundant, coming either from volcanic activity or chemical processes associated with life. So if we find methane on Mars that means that the planet is not geologically dead after all, which would be a major discovery in itself, or that there are organic processes taking place.

PFS will also provide a global circulation model of the Martian atmosphere, and there is another PFS due to fly on ESA's Venus Express mission. So we will have detailed information on the composition of the atmospheres of all three terrestrial planets, and the ways they differ will give us insight into their different histories.

Studying the surface, the PFS will work in tandem with the Omega spectrometer, which has a lower spectral capability but can produce images, unlike PFS. Only PFS has the very high spectral resolution to identify hydrated minerals on the surface, which are important to understand the story of water on early Mars.

Now the unknown lands are in space, and it's a function of human beings to seek adventure in new lands.

ESA: If there's one thing you could say to someone wanting to enter the space field, what would it be?

Vittorio Formisano

There have been oscillations in the space field, depending on the funding, but in the end the human future is in space – the solutions to all our problems in the world, whether resources or otherwise, will be found there. Without space we are bottled up in one small place, physically and intellectually.

In the past there were always some unknown lands we could go to, but now the unknown lands are in space, and it's a function of human beings to seek adventure in new lands. That's why children are so fascinated by space; they retain a sense of adventure that adults have lost.