Mysterious disk of blue stars around a black hole

Astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have identified the source of a mysterious blue light surrounding a 'super-massive' black hole in our neighbouring Andromeda Galaxy (M31).

Astronomers at the University of Washington first spotted the strange blue light in 1995 with the Hubble Space Telescope. They thought the light might have come from a single, bright blue star or perhaps from a more exotic energetic process.

Three years later, Hubble was used again to study the blue light, and observations indicated that the blue light was a cluster of blue stars. These stars are whipping around the black hole in much the same way as planets in our Solar System are revolving around the Sun.

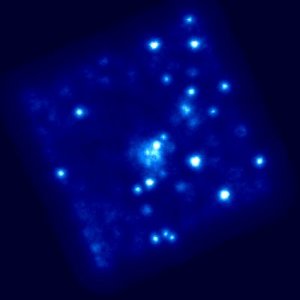

Now, new spectroscopic observations by Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) reveal that the blue light consists of more than 400 stars that formed in a burst of activity about 200 million years ago.

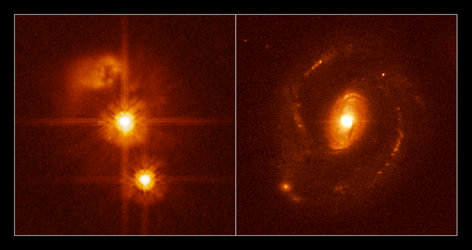

The stars are tightly packed in a disk that is only a light-year across. The disk is nested inside an elliptical ring of older, cooler, redder stars, which was seen in previous Hubble and ground-based observations.

Astronomers are perplexed about how the pancake-shaped disk of stars could form so close to a giant black hole. In such a hostile environment, the black hole’s tidal forces should tear matter apart, making it difficult for gas and dust to collapse and form stars. The observations, astronomers say, may provide clues to the activities in the cores of more distant galaxies.

By finding the disk of stars, astronomers also have collected what they say is strong evidence for the existence of the huge black hole. The evidence has helped astronomers rule out all alternative theories for the dark mass in the Andromeda Galaxy’s core, which scientists have long suspected was a black hole. They also calculated that the black hole's mass is 140 million times that of the Sun, which is three times more massive than once thought.

The black hole and the disk of stars are not the only pieces of architecture in Andromeda's core. Hubble was used in 1993 to discover that the galaxy appears to have a double cluster of stars at its centre. This finding was a surprise, because two clusters should merge into one in only a few hundred thousand years.

It was suggested that the 'double nucleus' was actually a ring of old, red stars. The ring looked like two star clusters because astronomers were only seeing the stars on the opposite ends of the ring. The ring is about five light-years from the black hole and its surrounding disk of blue stars. The disk and the ring are tilted at the same angle as viewed from Earth, suggesting that they may be related.

Although astronomers are surprised to find a blue disk of stars swirling around a supermassive black hole, they also say the puzzling architecture may not be that unusual.

Our own Milky Way apparently has even younger stars close to its own black hole. It seems unlikely that only the closest two big galaxies should have this odd activity, and other galaxies have been seen with a double nucleus, so this behaviour may not be the exception but the rule.

For more information:

Ralf Bender

Universitaets-Sternwarte der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität

Tel: +49 89 2180 5999

E-mail: bender @ usm.uni-muenchen.de

Lars Lindberg Christensen

Hubble ESA Information Centre, Garching, Germany

Tel: +49 89 3200 6306

Mobile: +49 173 3872 621

E-mail: lars @ eso.org

Donna Weaver

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, USA

Tel: +1 410 338 4493

E-mail: dweaver @ stsci.edu

Rebecca Johnson

University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas

Tel: +1 512 475 6763

E-mail: rjohnson @ stardate.utexas.edu

Doug Isbell

National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, Arizona

Tel: +1 520 318 8214

E-mail: disbell @ noao.edu