Rosetta’s last words: science descending to a comet

ESA’s Rosetta completed its incredible mission on 30 September, collecting unprecedented images and data right until the moment of contact with the comet's surface.

Rosetta’s signal disappeared from screens at ESA’s mission control at 11:19:37 GMT, confirming that the spacecraft had arrived on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko and switched off some 40 minutes earlier and 720 million kilometres from Earth.

One of the final pieces of information received from Rosetta was sent by its navigation startrackers: a report of a ‘large object’ in the field of view – the comet horizon.

Reconstruction of the final descent showed that the spacecraft gently struck the surface only 33 m from the target point.

The accuracy once again highlighted the excellent work of the flight dynamics specialists who supported the entire mission.

The spot, just inside an ancient pit in the Ma’at region on the comet’s ‘head’, was named Sais, after a town where the Rosetta Stone was originally located.

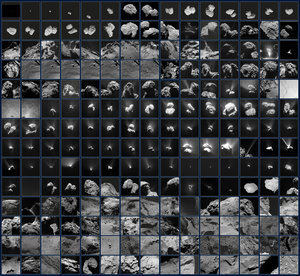

Numerous images were taken of the neighbouring pit, capturing incredible details of its layered walls that will be used to help decipher the comet’s geological history.

The final image was acquired about 20 m above the impact point. In addition, a number of Rosetta’s dust, gas and plasma analysis instruments collected data.

The pressure of the gas outflow from the comet was seen to rise as the surface neared. Scans revealed temperatures between about –190ºC and –110ºC down to a few centimetres below the surface. The variation was most likely due to shadows and local topography as Rosetta flew across the surface.

A last measurement of water vapour emission was made on 27 September, estimating the comet was emitting the equivalent of two tablespoons of water per second. During its most active period in August 2015, estimates were in the region of two bathtubs’ worth of water every second.

The first indications from spectral readings show there to be no significant differences in surface composition at the high resolutions obtained all the way down, and there was no obvious indication of small icy patches near the landing site.

The measurements also suggest an increase in very small dust grains – possibly around a millionth of a millimetre – close to the surface.

The last observation of the gas coma surrounding the comet was made the day before the final descent. Carbon dioxide was still being outgassed, at a greater distance from the Sun than when the comet was approaching it.

Stable solar wind conditions reigned during the final measurements of the solar wind and interplanetary magnetic field, providing ‘quiet’ background values that will be important for calibration.

Decreasing comet plasma densities were observed from about 2 km above the surface, with no obvious detection of local outgassing from the Ma’at pits.

Magnetic field measurements down to an estimated 11 m above the surface confirmed the previous observations of the comet as a non-magnetic body.

No large dust particles were collected during the descent, in itself an interesting result. First impressions are that the observed water vapour production was too low to lift dust grains above a detectable size from the surface.

“It’s great to have these first insights from Rosetta’s last set of data,” says Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta Project Scientist. “Operations have been completed for over two months now, and the instrument teams are very much focused on analysing their huge datasets collected during Rosetta’s two-plus years at the comet.

“Data from this period will eventually be made available in our archives in the same way as all Rosetta data.”

Notes for Editors

More details are provided in the complementary in-depth blog post here.

For more information, please contact:

Matt Taylor

ESA Rosetta project scientist

Email: matt.taylor@esa.int

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Tel: +31 71 565 6799

Mob: +31 61 594 3 954

Email: markus.bauer@esa.int

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland