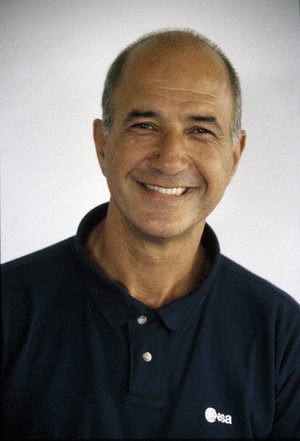

Ernst Messerschmid: STS-61A Payload Specialist

Former head of ESA's European Astronaut Centre, Ernst Messerschmid became the joint third German astronaut in space (with Reinhard Furrer) as a Payload Specialist on flight STS-61A of the Space Shuttle Challenger from 30 October to 6 November 1985, on the German Spacelab D1 mission.

Born in Reutlingen, Germany, on 21 May 1945, Messerschmid studied physics at the University of Tübingen and Bonn, from 1967 to 1972. After graduating, he worked at CERN and as a research assistant at the University of Freiburg/Breisgau where he received his doctorate in 1976.

He was working on space technology and utilisation when he applied for the first ESA astronaut selection in 1978. Following this, he joined the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Oberpfaffenhofen, where he worked on satellite-based search and rescue communication systems.

In 1983, he was selected as a DLR science astronaut and was assigned to the crew of the German Spacelab D1 mission.

After his flight, Messerschmid became Professor and Director of the Institute of Space Systems at the University of Stuttgart. In 2000, he joined ESA to become Head of the European Astronaut Centre, in Cologne, Germany.

He left ESA in 2004 and returned to his Professorship in Astronautics and Space Stations at the University of Stuttgart.

Some of our results changed the textbooks. We learned a lot about the relevance of gravity on Earth as a whole and the changes as we go into space.

ESA: How do you feel about the Spacelab D1 mission now, looking back after 25 years?

Messerschmid

Well it is now better understood what the role was of those early science-driven missions. The first Spacelab mission was the first ESA/NASA mission, with Ulf Merbold, followed by a Spacelab mission without a pressurised module, and then the next one was ours with Spacelab D1. We were the first to do exclusively a series of experiments covering all domains of microgravity research, that is, fundamental physics, materials sciences, life sciences and also technology experiments.

Today we know that some of our results changed the textbooks, or are recognised as drivers for better production techniques on Earth, in areas such as solidification, diffusion or crystal growth. We learned a lot about the relevance of gravity on Earth as a whole and the changes as we go into space.

The second equally important fact is that Spacelab created a user community for using human spaceflight missions, not only for microgravity research but also for other purposes. Without that community backing us we would not have embarked with our relatively small investment of Europe as almost equal partners in programmes such as the ISS, equal as in using the ISS for high-quality science.

I’m very proud of our flight, because we did what was expected. After landing, it was classed as a successful Spacelab mission. About 95% of objectives were achieved, although there were problems in the first few days. We had a leak and we were told if we didn’t fix it, we were flying back after two days. Then we had problems with some sensors in our space furnace. Out of 75 experiments, we couldn't have carried out 12 without repairing them first.

With the exception of a few items, everything was done. We compensated for the inefficiency of the first days by working overtime, 16-18 hours a day, but I regret not having more time to spend for myself, to enjoy microgravity or look out of the window. This more egoistic attitude is only developed when you get more than one flight!

ESA: This was a very international crew, with American, German and Dutch astronauts, why was that special?

Messerschmid

The payload was mostly German, the payload control centre was at Oberpfaffenhoffen, where it is today for Columbus on the ISS. This was a logical first step in view of what we do today for the ISS. In Germany, we had been in the driving seat in configuring the payload and the operations. That was a bit different from the first Spacelab mission two years earlier. We booked the Space Shuttle as a taxi and we wanted to run the mission as we thought necessary.

We had two NASA pilots, three NASA mission specialists and three payload specialists, two from Germany and one from ESA, owing to the fact that we had new payloads from ESA and because of the ESA contribution to the mission. Because ESA’s Ulf Merbold flew on the first Spacelab, the next ESA astronaut would be either Wubbo Ockels or Claude Nicollier. Wubbo had been back-up on Spacelab 1, so he was next in line logically.

In fact one year before the flight, we did not know that we would have a third payload specialist slot. The ESA seat for Wubbo was given, but the seat for Reinhard Furrer or me had to be challenged! Furrer and I had always said that there was too much work with 70 or so experiments, and that it could only be done with three specially trained science astronauts. But then we identified the potential of putting in another seat at the back of the mid-deck. NASA was convinced.

With the eighth seat, this was the largest Shuttle crew ever flown, with the same eight persons up and down. Another unique thing about this crew was that all eight astronauts had a PhD and all eight had their own pilot’s licence.

ESA: Did your flight into space change you personally?

Messerschmid

It changes you for sure when you sit on a Shuttle ride to space with all that thrust behind you and you get that experience. Usually I say that, as payload specialists or as users of space, we did not have the same kind of responsibilities as the other crew, we were reserved as scientists. But we flew on the mission, and shared the same environment and the authenticity of looking down at Earth from space.

Of course, emotionally it is fantastic, to have a very demanding job done in a very short time. The risk of not surviving was not the biggest stress, what I felt more was that behind each experiment there was one or two professors and two to three PhD students, and that I could not come back and look them in the eye without having sufficient data points for them.

ESA: Spacelab D1 was 25 years ago, what do think will be challenges of space exploration in the next 25 years?

Messerschmid

It will be different from the Apollo times. There will probably be somewhat different models of agreements for international cooperation, and probably more countries to join. For example on the ISS, already 30 countries are involved under the five main partners, and maybe more will join. I have been very active in the International Academy of Astronautics, and was a member of an independent study group where we looked at future missions and there are not that many destinations where we can go within the next 50 years.

The ultimate goal is Mars, but the next step is probably going to one of the libration points, it would be one of the Sun/Earth libration points, e.g. L2 to service and repair one of the 10 or more telescopes which will circulate there in about a decade, in my opinion. According to the US plans, maybe we could fly to an asteroid by 2025 or later and then even a flyby of Mars and maybe stopping off at Phobos, one of the two moons of Mars, in 2035. I think this is the right way to go, I was never too much in favour of going back to the Moon because I didn’t see the sustainability. It would only make sense to go to the Moon if you have solid plans for a permanently evolving infrastructure. But this was never the case for the Constellation programme.

The decisions being taken now are in the right direction, but no one in the USA knows how these discussions will turn out because first we need a transportation system to follow the Space Shuttle. The critical element of any future exploration programme is a heavy-lift vehicle, capable of launching at least 80 tonnes into Earth orbit, and now there is competition between the choice of liquid propellant systems or solid propellant systems. There is even an idea to use the Shuttle design but to replace the Orbiter with a cargo vehicle.

Maybe we could fly to an asteroid by 2025 or later, then even a flyby of Mars and maybe stop off at Phobos, one of the two moons of Mars, in 2035.

ESA: Did you always want to go into space from an early age?

Messerschmid

No, that came on very late. But I had been influenced by studying physics, and I was in my third semester at university when Apollo 11 landed on the Moon. But then I did my PhD at CERN in Geneva. This stimulated my interest in international jobs in science, and I even worked for some time at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in the USA. Just when I had finished my PhD, I listened to a radio interview with one of the leading space medicine doctors talking about the upcoming selection of ESA astronauts in early 1977.

In the interview, he described the characteristics needed to be successful, and for each one I put a mental checkmark alongside, so at the end of the interview I thought if this is all, then I probably qualify! I applied when the selection was announced in Germany at a national level, and was in the last five out of 1000 entries. Out of those five, three of us eventually flew into space: Ulf as an ESA astronaut, Reinhard and myself.