Europeans in Apollo: The Wright Stuff

An advertisement in a daily newspaper brought British engineer Keith Wright to the United States and made a lasting impression on the Moon.

At the height of the Space Race, Keith Wright was a young engineer working on the Europa 1 launcher at De Havilland Propellers in the UK. It was his first job after university and part of a lifelong fascination with space.

“I was doing trials, which means writing test procedures and countdown operations, for Blue Streak. That was how I started and then I moved on to coordinating activities between the three countries that were building the three stages of what became Europa – UK, France and Germany,” he says.

“I’d been a space enthusiast since I was very young – Dan Dare and all that stuff – and I saw an ad in the Daily Telegraph to work on Apollo. It was for Bendix Aerospace Systems in Michigan, and I got the job along with 26 other English people. Bendix had got the contract to build the experiments for the Apollo programme and they didn’t have enough engineers to do the job so they came over to the UK.”

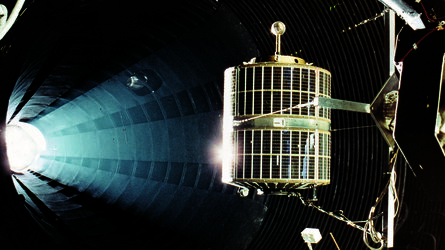

Keith’s responsibility was to help develop the test programme and procedures that would be needed at the Kennedy Space Center for pre-launch operations of the Apollo Lunar Science Experiments Package – known as ALSEP. However, the first Apollo landing mission did not emphasise science very much, since landing on the Moon first was the main priority.

“The Apollo 11 experiments were therefore to be very simple. NASA had become concerned as to exactly what the astronauts could do on the Moon and firstly wanted to concentrate on proving the landing and return capability. So Bendix actually had to very rapidly produce a simplified set of experiments, which was just a seismometer and a laser reflector.

Following Apollo 11, we had the full ALSEP programme on all of the missions. We had four experiments on each flight powered by a small nuclear generator, an RTG. They were designed to run for a year; they ran for seven years. And we got an enormous amount of data from them.”

Preparing for the first lunar landing, everything had to be rehearsed and checked carefully. This meant Keith got to meet the people who would make history in July 1969.

“I suppose one of the strongest memories I have is briefly working with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as I was working on the experiments that they were going to put out on the lunar surface. They came along to our facility at KSC to practise what they were going to do on the Moon. They had training hardware which they had been using in Houston but they needed to try the experiment deployment with the real hardware before they flew to the Moon.”

In August 1968, Keith and his team left Michigan for Florida, where he settled in happily with his family. After experiencing the intensity of the launch of the Apollo 11 Saturn V at the Kennedy Space Center, he gathered with colleagues to watch the landing on television, or in their case, three televisions.

“We were a very small team from Bendix, so three of us got together – we were renting apartments close to each other at the time – and three of us got together with three different TVs. We all brought our own TVs in because there were only three channels at the time and we wanted to have a picture on each channel so we wouldn’t miss anything that was being transmitted!”

Keith heard the television announcers say that the experiments had been deployed; knowing not just that his work had reached the Moon – but also something more personal.

“I didn’t think overly much of it at the time but when we were restowing the experiments after the crew had deployed them as they would on the Moon, there were two brackets that held the solar panels folded, and our NASA principal engineer said, ‘Why don’t we sign the back of one of them?’ This was a NASA suggestion!

“The fronts of the brackets were coated in thermal paint but the back was anodised aluminium so we signed it with ball pens and I put my name.

"As I was the only UK guy down there, I put UK and drew a little union flag. We then wrote a non-conformance report saying this bracket had been contaminated. It was all official.

“So we cleaned it with isopropyl alcohol and reinspected it and you could still see the scratches of our signatures. We said, ‘Well this is going to be thrown away on the Moon, those scratches don’t affect how it’s going to work, leave them on there’. So my signature is still on the Moon.”

Keith stayed with Apollo, but like many who worked on those missions, could see that he would need to plan for a new chapter in his career as the programme drew to a close. He returned to Europe where de Havilland had become Hawker Siddeley Dynamics. While working there, he made the move to ESA.

“Most of the good jobs at the Cape for the shuttle were already taken so I looked back in Europe and thought ‘Wow Europe is getting going!’ I went back to my old company, which had now become Hawker Siddeley Dynamics and I got recruited by them to work on the OTS satellite, which at that time was an ESRO project, it was Europe’s first communications satellite.

“I worked on that for three years through the bid phase and the early beginning of the development programme, and a colleague who worked for one of our sub-contractors who I had been working with, Lars Tedeman, moved to ESA on the Spacelab programme and as a result I joined ESA in April of 1975, also on the Spacelab programme.”

Joining ESA meant a move to the Netherlands, where Keith lived and worked for 19 years before opting for early retirement. He still returned to Florida, where he had bought a sailing boat, taking in some Space Shuttle launches too – 'Not quite as thunderous but off the pad a lot faster' than a Saturn V. Now he’s back in the UK, using his ESA experience to encourage the next generation of space engineers and scientists.

“One of the things I do is to talk to schools and try and use space to encourage the children to get into science subjects. Using space we can also tell them a little bit about the employment opportunities in the space business. In England, the space business is expanding between 7–9% at the moment so there are employment opportunities. We also tell them about ESA, Airbus and Surrey Satellite and the new British space companies. One of the things I push is the ESA Young Graduate Trainee scheme.”

For the Moonlanding anniversary itself, Keith will be part of a community event called 'One Giant Leap' in Dorchester, linking the town’s Roman past – including a parade at the Maumbury Rings – with Apollo and the future.

“I’m very pleased that finally, it looks like we are getting plans to go back to the Moon. We need to know whether we can use it as a resource for exploring the rest of the Solar System. It’s also going to be a good place where we can learn to live right off the planet.

“We need to become a multi-planetary species. We need to have our eggs in more than one basket.”

ESA is joining the international space community in celebrating the 50th anniversary of humankind first setting foot on the Moon and paying tribute to the men and women who took part in this endeavour, some of whom went on to work in later NASA, ESA and international space programmes. Today, ESA and our partners are busy preparing to return humans to the surface of the Moon. During this week, we will focus on the different lunar missions being prepared by ESA and highlight of some fascinating European contributions to lunar exploration.