Wind satellite vacuum packed

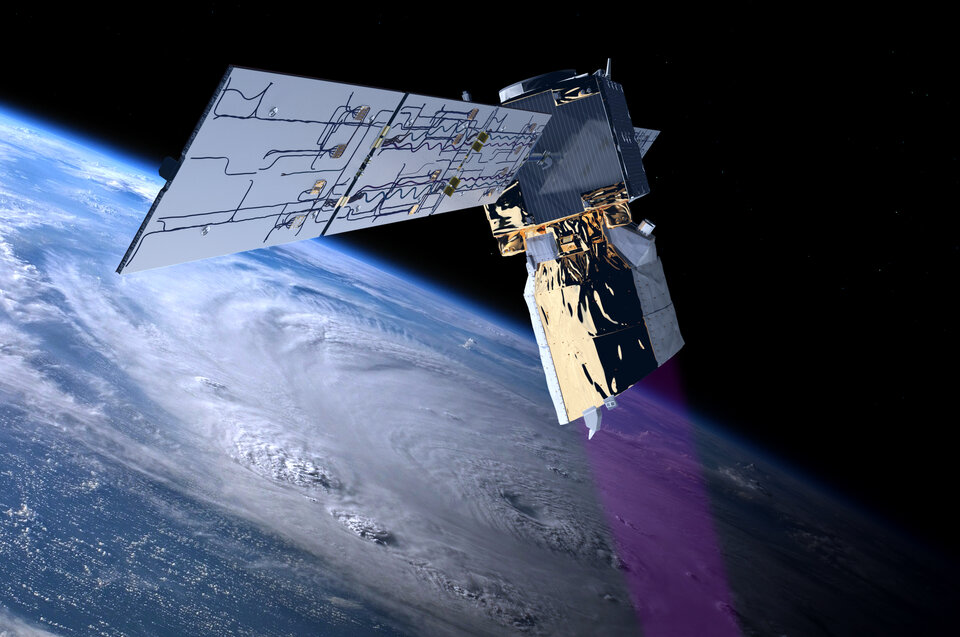

With liftoff on the horizon, ESA’s Aeolus satellite is going through its last round of tests to make sure that this complex mission will work in orbit. Over the next month, it is sitting in a large chamber that has had all the air sucked out to simulate the vacuum of space.

Aeolus carries one of the most sophisticated instruments ever to be put into orbit: Aladin, which includes two powerful lasers, a large telescope and very sensitive receivers.

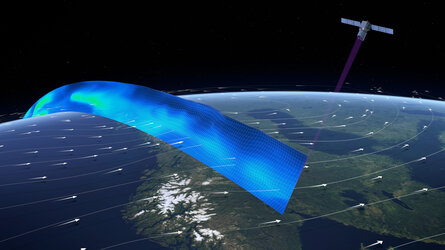

The laser generates ultraviolet light that is beamed down into the atmosphere to profile the world’s winds – a completely new approach to measuring the wind from space.

These vertical slices through the atmosphere, along with information it gathers on aerosols and clouds, will improve our understanding of atmospheric dynamics and contribute to climate research.

As well as advancing science, Aeolus will play an important role in improving weather forecasts.

Carrying such novel technology means there have been challenges during development – but advancing space technology is never easy.

With these difficulties in the past, the satellite is now undergoing final testing in Belgium before it is shipped to French Guiana for liftoff, which is scheduled for the middle of next year.

After having spent this spring at Airbus Defence and Space in Toulouse, France, where it was checked that it could withstand the vibration and noise liftoff and its ride into space, Aeolus has been at the Centre Spatial de Liège since May.

Here, it has just been enclosed in the thermal–vacuum chamber for the next 30 days or so.

With the satellite safely inside, the chamber door was closed a few days ago and the air was pumped out to create a vacuum.

Denny Wernham, ESA’s Aladin instrument manager, said, “It takes some time for the air and outgassing from the satellite to be pumped out of the chamber, but Aeolus finally faced ‘hard vacuum’ on 31 October.

“Tests are scheduled to run continuously over the next 33 days. We are particularly keen to see how well the laser transmits its pulses of ultraviolet light and the alignment of the instrument in this environment.

“Since the vacuum simulates the space environment, these tests are crucial to giving us confidence that it will work properly when it’s orbiting 320 km above our heads.”

Once these tests are done, the satellite will be transported back to Toulouse for final checks before being shipped across the Atlantic to Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana for launch on a Vega rocket.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland