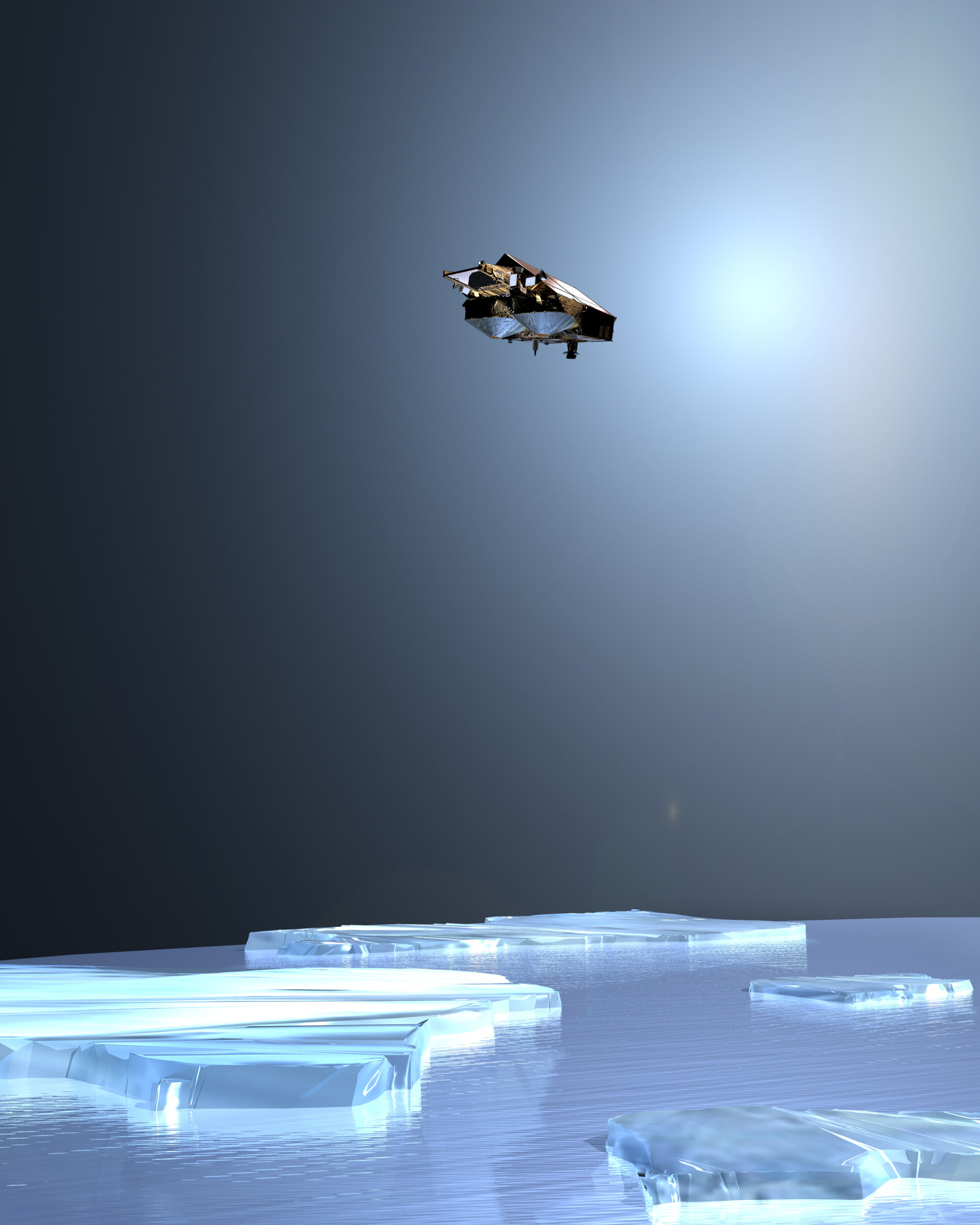

CryoSat: the ice edge holds the key

Until now satellites have not been able to monitor melting of ice at the very point where it is most significant: at the ice edge. CryoSat’s ability to do just that thrills scientists working in the field.

"CryoSat will pave the way for a better understanding of what happens to the ice at the exact point where things are the most interesting: at the ice edge where the majority of the melting takes place," says Danish glaciologist Carl Egede Bøggild.

Part of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) Bøggild heads a large-scale monitoring programme on the Greenland Ice. The programme utilises a combination of on-site measurements and satellite data.

"In principle you would prefer satellite data when you want to monitor large-scale developments," explains Bøggild. "However it has been a major problem that satellites have had trouble monitoring the very ice edge zone."

In order to measure the thickness of a given ice layer, a radar altimeter satellite emits a radar signal and later records it being reflected back out to space. The time taken for the signal to return can be utilised to calculate the exact ice height, from which its thickness can in turn be derived.

However the topography at the edge of an ice sheet can be very steep and uneven, making it difficult for the satellite to catch the reflected signal, or know precisely from which point within the ten-kilometre signal 'footprint' the signal is returning from. Often the uncertainty would be too large for the results to be reliable. The practical implication was that the entire ice edge remained inaccessible for satellite monitoring.

However the science team behind CryoSat has managed to tackle this problem. Its double-antenna design means it can measure the angle of the returning signal to put an exact location on where it comes from relative to the spacecraft track. The satellite will still be able to carry out its measurements, no matter how steep the ice surface may be.

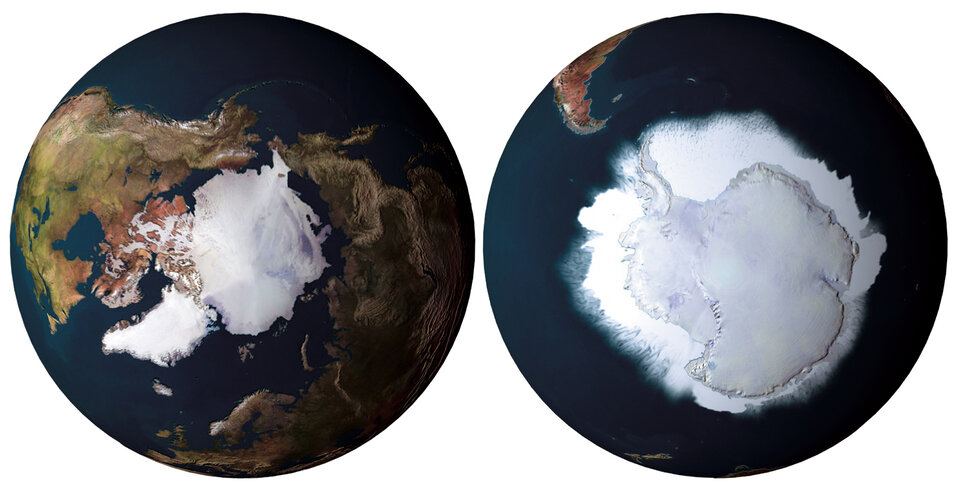

"To my mind the ice edge is the most interesting place to do science," the Danish glaciologist states. "In the middle of the inland ice things are very stable. As climate changes, the edge is where you will be able to observe the effect first.

"American airborne measurements have shown a thinning of the Greenland glaciers by one metre per year. However our measurements on location at the ice edge show melting on an even larger scale. Now we are anxious to learn what the measurements from CryoSat will show."

According to on-site measurements the Sermilik glacier in Southern Greenland is thinning between two and eight metres a year. Not all of this change is linked to climate change caused by human activities. The glaciologist compares the inland ice to dough for making a loaf of bread laid out on a kitchen table: "You see a slow movement from the middle towards the edge. In the case of the inland ice it may take thousands of years from a snow flake falls in the centre until it reaches the edge.

"You might say that the system has a certain built-in memory. Some of the melting we witness now is actually an aftermath of the last, mini Ice Age which ended in the last half of the 19th century".

Systematic monitoring of air temperature has taken place since 1875. Comparing the temperature levels with the actual melting one can determine that about half of the melting is linked to changes in climate. The other half will then have other causes – primarily the aftermath of the last Ice Age.

The Danish ice monitoring effort has found thinning of large areas of the inland ice. That goes for practically the entire ice edge zone. One interesting twist to the story is that in some areas thinning is taking place despite a drop in mean temperatures.

"This goes to show the complexity of the system," Bøggild adds. "Normally one would use the number of days with temperatures above zero degrees as an indicator of melting. Generally these two factors would be linked. However factors other than temperature may also be influencing melting. One of them is the amount of incoming solar radiation. This would make it possible to see these kind of surprising results locally".

Despite his great expectations for CryoSat, Carl Egede Bøggild underlines that satellites will not replace ground measurements: "Satellites will give us a far more accurate view of the amount of melting but they will not tell us why the melting is taking place. In order to improve your understanding of the causes you have to do research on site. Also we will have to keep on doing measurements on site in order to verify the findings of the satellites. We are talking about two different kinds of tools supplementing each other very well."

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland