Europe’s satellites track climate changes

In July an Ariane-5 launcher will send into orbit Europe’s big new environmental satellite, Envisat. Scientists will expect fresh insights from its data, into how the world is changing. The 8-tonne spacecraft will continue and extend the work of ESA’s ERS-1 and ERS-2, which since 1991 have established a distinctive role in watching global change, notably in the world’s oceans and ice sheets.

An important ozone monitor was added on ERS-2. One of the new instruments on Envisat will observe the variations in ocean colour due to the seasonal blooming of life, which plays a big but poorly understood part in controlling the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Improved instruments for gauging ozone and other trace gases are also on board.

Yet Envisat is just the flagship of a fleet of satellites being built in Europe to make better sense of the possibly adverse climate trends on the planet that is our only home in the desert of space.

While everyone wonders about unusual weather and what it may mean for the future, spacecraft are the world’s chief eyes on current weather and climate variations. Surface stations are scattered very unevenly around the globe. They are especially scarce in polar, oceanic and sparsely inhabited land regions where, some climate forecasters suggest, the greatest changes may be occurring. Only satellites can observe the weather and associated climatic and environmental changes comprehensively and objectively, day by day and decade by decade. So several ESA programmes converge on the issues of climate change.

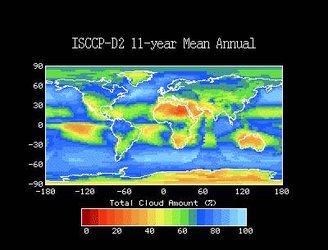

On behalf of EUMETSAT, ESA is developing two advanced satellites for routine weather observations. One is Meteosat Second Generation (MSG) to replace the Meteosat series that, since 1977, have watched the weather over Europe, Africa and adjacent regions and ocean from a geostationary vantage point. Besides its familiar use in daily weather forecasting, Meteosat provides a huge archive for climate studies, for example in helping to reveal changes in the Earth’s cloud cover from year to year. MSG-1 is scheduled for launch in 2002. It will generate sharper images twice as often, and with twelve wavelength channels rather than the three in the current Meteosat. It will also carry the Geostationary Earth Radiation Budget experiment to monitor the difference between reflected sunlight and the infrared rays emitted from the upper atmosphere, which are partially blocked by greenhouse gases.

From 2005 the first Metop satellite will orbit over the poles. In a cooperative programme between EUMETSAT and ESA, Metop is the space segment of the EUMETSAT Polar System. This in turn is part of a joint European-US satellite system coordinated with the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The European and American satellites will share some basic instruments, including an Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit to measure the temperature of the air at many levels in the atmosphere. A puzzle about climate change is that the rising global temperatures inferred from surface stations are not matched by any long-term warming of the lower atmosphere. Additional European instruments on Metop will improve atmospheric soundings, and measure atmospheric ozone and near-surface winds over the ocean.

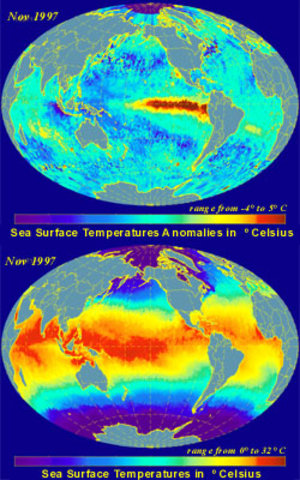

ESA’s Earth Explorer programme aims to advance earth science and the techniques of observation from space, beyond the present capabilities of current generation of Earth Observation satellites. The first core mission of this programme is GOCE (Gravity and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Mission) due for launch in 2004/5. It will measure regional variations in the Earth’s gravity more accurately than ever before. One of its benefits will be a better understanding of the ocean currents, which play a major role in the climate by transporting huge amounts of heat between different regions.

The second Earth Explorer core mission will be ADM (Atmospheric Dynamics Mission, 2004/5). It aims to fill a big gap in observations of the winds of the world. The computer models that calculate daily weather forecasts and make climate predictions, have to diagnose and predict the winds at all levels in the atmosphere. Observations that might check whether the reckonings are correct are limited to those relatively few places where radiosonde weather balloons are flown routinely. Coverage of the oceans and the Southern Hemisphere is especially sparse. ADM will use an ultraviolet laser beam to measure wind speeds at 20 levels in the air, by detecting echoes from molecules and dust particles carried by the winds.

In addition to its core projects, ESA’s Earth Explorer programme supports smaller “opportunity” missions. Cryosat (2003/4) will find out whether the great ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland are melting as a result of global warming. It will also clarify the role of sea ice in climate variations. ERS-1 and ERS-2 have measured year-by-year variations in the thickness of the ice sheets with a radar altimeter, but have detected little change overall. This may be because the radar averages the ice altitudes across wide areas. To look for significant melting at the edges of the ice sheets, Cryosat will use twin radars to detect changes across areas just 250 metres wide.

Soil moisture and ocean salinity are the targets for SMOS, the second “opportunity” project. Life on land relies almost entirely on the thin layer of moisture in the soil that supplies the roots of plants, and any global or regional trends due to greater or lesser rainfall would be one of the most important indicators of climate change. SMOS (2005/6) will use a multi-beam radio telescope to detect 21-centimetre radiation from the land surface, the intensity of which is a good indicator of soil moisture. The same radiation coming from the ocean will reveal the salt content of the sea surface, which has a major influence on ocean currents and hence on the climate.

The role of the Sun as a natural agent of climate change is investigated by ESA’s Space Science Programme. Intense magnetic activity on the Sun seems linked to warming effects on the Earth, but the solar mood varies from decade to decade and century to century. When the ESA-NASA Ulysses spacecraft first flew over the solar poles in 1994-95, it showed that the magnetic field far from the Sun is much more uniform that experts expected. As a result, scientists were able to deduce, from magnetic records on the Earth, that the interplanetary magnetic field doubled in strength during the 20th Century, probably with related contributions to global warming.

The ESA-NASA SOHO spacecraft, stationed 1.5 million kilometres out on the sunward side of the Earth, has monitored changes in the Sun since 1996. It measured an expected increase in the intensity of sunlight while the Sun approached its present maximum of magnetic activity, as indicated by a rising count of sunspots. SOHO has also discovered an ever-varying dynamo deep beneath the surface that seems to be responsible for the Sun’s outward show of magnetism.

When the Sun’s role in the Earth’s climate changes is better defined, anticipating its mood will be important for forecasting. Some experts think that the best predictor of the intensity of solar activity is the strength of the magnetic field at the Sun’s poles, but this is hard to gauge. ESA’s successor to SOHO will be the Solar Orbiter, due for launch around 2010. For one month in every five, the Solar Orbiter will swoop close to the Sun and observe its stormy atmosphere in far greater detail than ever before. It will also use encounters with the planet Venus to slant its orbit and achieve a better view of the Sun’s poles and the magnetism there.

ESA is now examining a selection of five proposals for further core missions in the Earth Explorer programme. These would investigate atmospheric chemistry, clouds and aerosols, ecological changes, or water vapour in the atmosphere. The exuberance of the proposals, backed by dozens of scientists from ESA’s member states and other countries, is a sure sign that many new possibilities remain for learning more about our planet from space. By 2015, when the Solar Orbiter will be helping scientists to forecast the Sun’s activity for the following decade, scientific understanding of both manmade and natural climate change should be far deeper than it is now - thanks at least in part to Europe’s climate-tracking spacecraft.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland